| 169. Toward Imagination: The Twelve Human Senses

20 Jun 1916, Berlin Tr. Sabine H. Seiler Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| On theology there were only the most essential works, the Bollandist writings and a good deal of Franciscan literature, Meister Eckhart, writings on the spiritual exercises, Catherine of Genoa, the mysticism of Gorres and Mohler's symbolism. On philosophy there were more books: all of Kant's works, including the collected volumes of the Kant Society, also Deussen's Upanishads and his history of philosophy, Vaihinger's philosophy of the As if, and very many books on epistemology. |

| Lost the first battle of the Marne (Sept. 1914) and was relieved of his command (Nov. 1914).2. Eduard von Hartmann, 1842–1906, German philosopher. |

| 10. Richard M. Meyer, 1860–1914, German philologist.11. Franz Ferdinand, 1863–1914, Archduke of Austria. |

| 169. Toward Imagination: The Twelve Human Senses

20 Jun 1916, Berlin Tr. Sabine H. Seiler Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Before coming to the topic of today's talk, I would like to say a few words about the great and grievous loss on the physical plane we have suffered in recent days. You will undoubtedly know what I mean: the day before yesterday, Herr von Moltke's soul passed through the gate of death.1 What this man was to his country, the outstanding part he played in the great and fateful events of our time, the significant, deep impulses growing out of human connections that formed the basis of his actions and his work—to appreciate and pay tribute to all this will be the task of others, primarily of future historians. In our age it is impossible to give an entirely comprehensive picture of everything that concerns our time. As I said, we will not speak of what others and history will have to say, but I am absolutely convinced that future historians will have very much to say about von Moltke. However, I would like to say something that is now in my soul, even if I have to express it at first symbolically; what I mean will be understood only gradually. This man and his soul stand before my soul as a symbol of the present and the immediate future, a symbol born out of the evolution of our time, in the true sense of the word a symbol of what should come to pass and must come to pass. As we have repeatedly emphasized, we are not trying to integrate spiritual science into contemporary culture out of somebody's arbitrary impulses, but because it is needed in these times. There will not be a lasting future if the substance of this spiritual science does not flow into human development. This is the point, my dear friends, where you can see the greatness and significance we find when we think of Herr von Moltke's soul. He participated most actively in the busy life of our era, the life that developed out of the past and led to the greatest crisis humanity ever had to go through in its history. He was one of the leaders of the army and was right in the middle of the events that inaugurated our fateful present and future. Here was a soul, a personality, who did all this and, at the same time, also was one of us, seeking knowledge and truth with the most holy, fervent thirst for knowledge that ever inspired a soul in our day and age. That is what we should think of. For the soul of this personality, who has just died, is more than anything else an outstanding historical symbol. It is profoundly symbolic that he was one of the leading figures of the outer life, which he served, and yet found the bridge to the life of the spirit we seek in spiritual science. We can only wish with all our soul that more and more people in similar positions do as he has done. This is not just a personal wish, but one born out of the need of our times. You should feel how significant an example this personality can be. It does not matter how little other people speak about the spiritual side of his life; in fact, it is best for it not to be talked about. But what von Moltke did is a reality and the effects are what is important, not whether it is discussed. Herr von Moltke's life can lead us to realize that he interpreted the meaning of the signs of the times correctly. May many follow this soul who are still distant from our spiritual science. It is true, and we should not forget it, that this soul has given as much to what flows and pulsates through our spiritual science as we have been able to give him. Now souls are entering the spiritual world bearing within them what they have received from spiritual science. What spiritual science strives for has united with the soul of a person, who has died after a very active life. This then works as a deeply significant, powerful force in the realm we want to explore with the help of our spiritual science. And the souls now present here who understand me will never forget what I have just said about how significant it is that souls now take what has flowed for many years through our spiritual science into the spiritual world, where it will become strength and power. I am not telling you this to assuage in a trivial way the pain we feel about our loss on the physical plane. Pain and sorrow are justified in a case like Herr von Moltke's death. But only when pain and sorrow are permeated by a sound understanding of what underlies them can they become great and momentous active forces. Take, therefore, what I have said as the expression of sorrow over the loss the German people and all humanity have experienced on the physical plane. Let us stand up, my dear friends, and recite this verse:

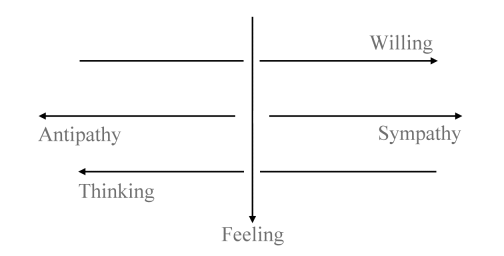

My dear friends, as I have often said, the occult substance that flows through our whole evolution has found its outer expression or manifestation in all kinds of more or less occult and symbolic brotherhoods and societies. In my recent talks I have characterized them in more detail as really quite superficial. We are now living in an age when the occult knowledge from the spiritual world must be given to people in a new way, as we have been trying to do for many years now, because the previous ways are obsolete. Granted, they will continue to exist for a time, but they are quite obsolete, and it is important that we understand this in the right way. As you know, I like to call our spiritual science anthroposophy, and a few years ago when I gave lectures here, I called them lectures on anthroposophy. Last time, I referred to these lectures on anthroposophy, particularly to my emphasis on the fact that human beings actually have twelve senses. I explained that, as far as our senses are concerned, what is spread out over our nerve substance is organized according to the number twelve because the human being is in this most profound sense a microcosm and mirrors the macrocosm. In the macrocosm the sun moves through twelve signs of the zodiac in the course of a year, and the human I lives here on the physical plane in the twelve senses. Things are certainly rather different out there in the macrocosm, especially in regard to their sequence in time. The sun moves from Aries through Taurus, and so on, and back again through Pisces to Aries as it makes its yearly course through the twelve signs of the zodiac. Everything we have in us, even everything we experience in our soul, is related to the outer world through our twelve senses. These are the senses of touch, life, movement, balance, smell, taste, sight, warmth, hearing, speech, thinking, and the sense of the I. Our inner life moves through this circle of the twelve senses just as the sun moves through the circle of the twelve signs of the zodiac. But we can take this external analogy even further. In the course of a year, the sun has to move through all the signs of the zodiac from Aries to Libra; it moves through the upper signs during the day and through the lower ones at night. The sun's passage through these lower signs is hidden from outer light. It is the same with the life of our soul and the twelve senses. Half of the twelve are day senses, just as half of the signs of the zodiac are day signs; the others are night senses. You see, our sense of touch pushes us into the night life of our soul, so to speak, for with the sense of touch, one of our coarser senses, we bump into the world around us. The sense of touch is barely connected with the day life of our soul, that is, with the really conscious life of the soul. You can see for yourself that this is true when you consider how easily we can store the impressions of our other senses in our memory and how difficult it is to remember the impressions of the sense of touch. Just try it and you'll see how difficult it is to remember, for example, the feel of a piece of fabric you touched a few years ago. Indeed you'll find you have little need or desire to remember it. The impression sinks down in the same way as the light fades into twilight when the sun descends into the sign of Libra at night, into the region of the night signs. And thus other senses are also completely hidden from our waking, conscious soul life. As for the sense of life, conventional psychological studies hardly mention it at all. They usually list only five senses, the day senses or senses of waking consciousness. But that need not concern us further. The sense of life enables us to feel our life in us, but only when that life has been disturbed, when it is sick, when something causes us pain or hurts us. Then the sense of life tells us we are hurting here or there. When we are healthy, we are not aware of the life in us; it sinks into the depths, just as there is no light when the sun is in the sign of Scorpio or in any other night sign. The same applies to the sense of movement. It allows us to perceive what is happening in us when we have set some part of our body in motion. Conventional science is only now beginning to pay attention to this sense of movement. It is only just beginning to find out that the way joints impact on one another—for example, when I bend my finger, this joint impacts on that one—tells us about the movements our body is carrying out. We walk, but we walk unconsciously. The sense underlying our ability to walk, namely, the perception of our mobility, is cast into the night of consciousness. Let us now look at the sense of balance. We acquire this sense only gradually in life; we just don't think about it because it also remains in the night of consciousness. Infants have not yet acquired this sense, and therefore they can only crawl. It was only in the last decade that science discovered the organ for the sense of balance. I have mentioned the three canals in our ears before; they are shaped like semicircles and are vertical to each other in the three dimensions of space. If these canals are damaged, we get dizzy; we lose our balance. We have the outer ears for our sense of hearing, the eyes for the sense of sight, and for the sense of balance we have these three semicircular canals. Their connection with the ears and the sense of hearing is a vestige of the kinship between sound and balance. The canals, located in the cavity in the petrosal bone, consist of three semicircles of tiny, very minute, bones. If they are the least bit injured, we can no longer keep our balance. We acquire our receptivity for the sense of balance in early childhood, but it remains submerged in the night of consciousness; we are not conscious of this sense. Then comes the dawn and casts its rays into consciousness. But just think how little the other hidden senses, those of smell and taste, actually have to do with our inner life in a higher sense. We have to delve deeply into the life of our body to be able to get a sense for smell. The sense of taste already brings us a growing half-light; day begins to dawn in our consciousness. But you can still make the same experiment I mentioned before concerning the sense of touch, and you will find it very difficult to remember the perceptions of the senses of smell and of taste. Only when we enter more deeply into our unconscious with our soul does the latter consciously perceive the sense of smell. As you may know, certain composers were especially inspired when surrounded by a pleasant fragrance they had smelled previously while creating music. It is not the fragrance that rises up out of memory, but the soul processes connected with the sense of smell emerge into consciousness. The sense of taste, however, is for most people almost in the light of consciousness, though not quite; it is still partly in the night of consciousness for most of us. After all, very few people will be satisfied with the soul impression of taste alone. Otherwise we should be just as pleased with remembering something that tasted good as we are when we eat it again. As you know, this is not the case. People want to eat again what tasted good to them and are not satisfied with just remembering it. The sense of sight, on the other hand, is the sense where the sun of consciousness rises, and we reach full waking consciousness. The sun rises higher and higher. It rises to the sense of warmth, to the sense of hearing, and from there to the sense of speech and then reaches its zenith. The zenith of our inner life lies between the senses of hearing and speech. Then we have the sense of thinking, and the I sense, which is not the sense for perceiving our own I but that of others. After all, it is an organ of perception, a sense. Our awareness of our own I is something quite different, as I explained in my early lectures on anthroposophy. What is important here is not so much knowing about our own I, but meeting other people who reveal their I to us. Perception of the other person's I, not of our own, that is the function of the I sense. Our soul has the same relationship to these twelve senses as the sun does to the twelve signs of the zodiac. You can see from this that the human being is in the truest sense of the word a microcosm. Modern science is completely ignorant of these things; while it does acknowledge the sense of hearing, it denies the existence of the sense of speech although we could never understand the higher meaning of spoken words with the sense of hearing alone. To understand, we need the sense of speech, the sense for the meaning of what is expressed in the words. This sense of speech must not be confused with the sense of thinking, which in turn is not identical with the ego sense. I would like to give you an example of how people can go wrong in our time in this matter of the senses. Eduard von Hartmann, who was a most sincere seeker, begins his book Basic Psychology with the following words as though he were stating a self-evident truth: “Psychological phenomena are the point of departure for psychology; indeed, for each person the starting point has to be his or her own phenomena, for these alone are given to each of us directly. After all, nobody can look into another's consciousness.”2 The opening sentence of a psychology book by one of the foremost philosophers of our time starts by denying the existence of the senses of speech, thinking, and the I. He knows nothing about them. Imagine, here we have a case where absurdity and utter nonsense must be called science just so these senses can be denied. If we do not let this science confuse us, we can easily see its mistakes. For this psychology claims we do not see into the soul of another person but can only guess at it by interpreting what that person says. In other words, we are supposed to interpret the state of another's soul based on his or her utterances. When someone speaks kindly to you, you are supposed to interpret it! Can this be true? No, indeed it is not true! The kind words spoken to us have a direct effect on us, just as color affects our eyes directly. The love living in the other's soul is borne into your soul on the wings of the words. This is direct perception; there can be no question here of interpretation. Through nonsense such as Hartmann's, science confines us within the limits of our own personality to keep us from realizing that living with the other people around us means living with their souls. We live with the souls of others just as we live with colors and sounds. Anyone who does not realize this knows absolutely nothing of our inner life. It is very important to understand these things. Elaborate theories are propagated nowadays, claiming that all impressions we have of other people are only symbolic and inferred from their utterances. But there is no truth in this. Now picture the rising sun, the emergence of the light, the setting sun. This is the macrocosmic picture of our microcosmic inner life. Though it does not move in a circle, our inner life nevertheless proceeds through the twelve signs of the zodiac of the soul, that is, through the twelve senses. Every time we perceive the I of someone else, we are on the day side of our soul-sun. When we turn inward into ourselves and perceive our inner balance and our movements, we are on the night side of our inner life. Now you will not think it so improbable when I tell you that in the time between death and rebirth the senses that have sunk deeply into our soul's night side will be of special importance for us because they will then be spiritualized. At the same time, the senses that have risen to the day side of our inner life will sink down deeper after death. Just as the sun rises, so does our soul rise, figuratively speaking, between the sense of taste and the sense of sight, and in death it sets again. When we encounter another soul between death and a new birth, we find it inwardly united with us. We perceive that soul not by looking at it from the outside and receiving the impression of its I from the outside; we perceive it by uniting with it. You can read about this in the lecture cycles, where I have described it, and also in An Outline Of Occult Science.3 In the life between death and rebirth, the sense of touch becomes completely spiritual. What is now subconscious and belongs to the night side of our inner life, namely, the senses of balance and movement, will then become spiritualized and play the most important part in our life after death. It is indeed true that we move through life as the sun moves through the twelve signs of the zodiac. When we begin our life here, our consciousness for the senses rises, so to speak, at one pillar of the world and sets again at the other. We pass these pillars when we move in the starry heavens, as it were, from the night side to the day side. Occult and symbolic societies have always tried to indicate this by calling the pillar of birth, which we pass on the way into the life of the day side, Jakim.4 Our outer world during the life between death and rebirth consists of the perceptions of the sense of touch spread out over the whole universe, where we do not touch but are touched. We feel that we are touched by spiritual beings everywhere, while in physical life it is we who touch others. Between death and rebirth we live within movement and feel it the same way a blood cell or a muscle in us would feel its own movement. We perceive ourselves moving in the macrocosm, and we feel balance and feel ourselves part of the life of the whole. Here on earth our life is enclosed in our skin, but there we feel ourselves part of the life of the universe, of the cosmic life, and we feel that we give ourselves our own balance in every position. Here, gravity and the constitution of our body give us balance, and usually we are not aware of this. During life between death and a new birth, however, we feel balance all the time. We have a direct experience of the other side of our inner life. We enter earthly life through Jakim, assured that what is there outside in the macrocosm now lives in us, that we are a microcosm, for the word Jakim means, “The divine poured out over the world is in you.” The other pillar, Boaz, is the entrance into the spiritual world through death. What is contained in the word Boaz is roughly this, “What I have hitherto sought within myself, namely strength, I shall find poured out over the whole world; in it I shall live.” But we can only understand such things when we penetrate them by means of spiritual knowledge. In the symbolic brotherhoods, the pillars are referred to symbolically. In our fifth post-Atlantean epoch they will be mentioned more often to keep humanity from losing them altogether and to help later generations to understand what has been preserved in these words. You see, everything in the world around us is a reflection of what lives in the macrocosm. As our inner life is a microcosm in the sense I have indicated, so humanity's inner life is built up out of the macrocosm. In our time, it is very important that we have the image of the two pillars I mentioned handed down to us through history. These pillars each represent life one-sidedly; for life is only to be found in the balance between the two. Jakim is not life for it is the transition from the spiritual to the body; nor is Boaz life for that is the transition from body to spirit. Balance is what is essential. And that is what people find so difficult to understand. They always seek one side only, extremes rather than equilibrium. Therefore two pillars are erected for our times also, and we must pass between them if we understand our times rightly. We must not imagine either the one pillar or the other to be a basic force for humanity, but we must go through between the two. Indeed, we have to grasp what is there in reality and not go through life brooding without really thinking, as modern materialism does. If you seek the Jakim pillar today, you will find it. The Jakim pillar exists; you will find it in a very important man, who is no longer alive, but the pillar still exists—it exists in Tolstoyism. Remember that Tolstoy basically wanted to turn all people away from the outer life and lead them to the inner.5 As I said when I spoke about Tolstoy in the early days of our movement, he wanted to focus our attention exclusively on what goes on in our inner life. He did not see the spirit working in the outer world—a one-sided view characteristic of him, as I said in that early lecture. One of our friends showed Tolstoy a transcript of that lecture. He understood the first two-thirds of it, but not the last third because reincarnation and karma were mentioned there, which he did not understand. He represented a one-sided view, the absolute suppression of outer life. It is painful to see him show this one-sidedness. Just think of the tremendous contrast between Tolstoy's views, which predominate among a considerable number of Russia's intellectuals, and what is coming from there these days. It is one of the most awful contrasts you can imagine. So much for one-sidedness. The other pillar, the Boaz pillar, also finds historical expression in our age. It too represents one-sidedness. We find it in the exclusive search for the spiritual in the outer world. Some years ago, this phenomenon appeared in America with the emergence of the polar opposite to Tolstoy, namely, Keely.6 Keely harbored the ideal of building a motor that would not run on steam or electricity, but on the waves we create when we make sounds, when we speak. Just imagine that! A motor that runs on the waves we set in motion when we speak, or indeed with our inner life in general! Of course, this was only an ideal, and we can thank God it was just an ideal at that time, for what would this war be like if Keely's ideal had been realized? If it is ever realized, then we will see what the harmony of vibrations in external motor power really means. This, then, is the other one-sidedness, the Boaz pillar. It is between these two pillars we must pass through. There is much, indeed very much, contained in symbols that have been preserved. Our age is called upon to understand these things, to penetrate them. Someday people will perceive the contrast between all true spirituality and what will come from the West if the Keely motor ever becomes a reality. It will be quite a different contrast from the one between Tolstoy's views and what is approaching from the East. Well, we cannot say more about this. We need to gradually deepen our understanding of the mysteries of human evolution and to realize that what will some day become reality in various stages has been expressed symbolically or otherwise in human wisdom throughout millennia. Today we are only at the stage of mere groping toward this reality. In one of our recent talks I told you that Hermann Bahr, a man I often met with in my youth, is seeking now—at the age of fifty-three and after having written much—to understand Goethe. Groping his way through Goethe's works, he admits that he is only just beginning to really understand Goethe. At the same time, he admits that he is beginning to realize that there is such a thing as spiritual science in addition to the physical sciences. I have explained that Franz, the protagonist of Bahr's recently published novel Himmelfahrt (“Ascension”), represents the author's own path of development, his path through the physical sciences.7 Bahr studied with the botanist Wiessner in Vienna, then with Ostwald in the chemical laboratory in Leipzig, then with Schmoller at the seminar for political economy in Berlin, and then he studied psychology and psychiatry with Richet in France. Of course, he also went to Freud in Vienna—as a man following up on all the various scientific sensations of the day would naturally have to do—and then he went to the theosophists in London, and so forth. Remember, I read you the passage in question, “And so he scoured the sciences, first botany with Wiessner, then chemistry with Ostwald, then Schmoller's seminar, Richet's clinic, Freud in Vienna, then directly to the theoso- phists. And so in art he went to the painters, the etchers, and so on.”8 But what faith does this Franz attain, who is really one of the urgently seeking people of the present age? Interestingly enough, he wanders and gropes, and then something dawns on him that is described as follows:

These thoughts occur to Franz after he has hurried through the world and has been everywhere, as I have told you, and has at last returned to his home, presumably Salzburg. That's where these thoughts occur to him, in his Salzburg home. I would like to mention in all modesty that he did not come to us; and we can get an idea of why Franz did not come to us. In his quest for people who are striving for the spirit, Franz remembers an Englishman he had once met in Rome and whom he describes as follows:

There you have a caricature of what I have told you, namely, that there is, as it were, a kingdom within a kingdom, a small circle whose power radiates into others. But the Englishman, and Franz with him, imagined this circle to be a community of Rabbis and Monsignors; as a matter of fact, they are precisely the ones who are not in it. But you see that Franz just gropes his way here. And why? Well, he remembers once again the eccentric whims of the Englishman:

Those he had given up! You see, there is such a groping and fumbling in our time. People like Bahr reach their old age before they understand anything spiritual, and then they have such grotesque ideas as we see here. This Franz is then invited to the house of a canon. This Salzburg canon is a very mysterious personality, and of great importance in Salzburg—the town Salzburg is not named, but we can nevertheless recognize it. He is of even greater importance than the cardinal, for the whole city no longer talks about the cardinal but about the canon although there are a dozen canons there. And so Franz gets the idea that maybe this very man is one of the white lodge. You know how easy it is to get such ideas. Well, Franz is invited to lunch at the canon's house. There are many guests, and the canon is really a very tolerant man; imagine, he is a Catholic canon, and yet he has invited a Jewish banker together with a Jesuit, Franz, and others, including a Franciscan monk. It is a very cheerful luncheon party. The Jesuit and the Jewish banker are soon talking—nota bene, the banker is one to whom practically everybody is indebted but who is really most unselfish in what he does and as a rule does not ask for repayment of what he apparently lends but instead only wants the pleasure of being invited to the house of a gentleman such as the canon once a year. The eager conversation between the Jesuit and this Jewish banker is altogether too much for Franz. He leaves them and goes into the library to escape their scandalous jokes, and the canon follows him.

Now what the canon finds in Goethe's scientific writings is characteristic, on the one hand, of what is actually contained there and can be understood by the canon and, on the other hand, of what the canon can understand by virtue of being a Catholic canon.

There the canon is right. We cannot understand the end of Faust if we don't know Goethe's scientific views.

That is what most people believe, that Goethe really was only pretending when he wrote the magnificent, grandiose final scene of Faust. “But the scientific writings reveal on every page how much of a Catholic Goethe was.” Yes, well, the canon calls everything he can understand, everything he likes, Catholic. We don't need to feel embarrassed about that.

For us, it would be particularly interesting to know what the canon calls “exaggerations.” Well, in any case, he calls them Catholic and goes on to say:

Imagine, a Catholic canon writing the resolutions of the Council of Trent next to the words of Goethe!9 In this juxtaposition you have what permeates all humanity and what we may call the core of spiritual life common to all people. This should not be taken as just so much empty rhetoric; instead it must he understood as it was meant. The canon continues:

What the canon adds to this we can be pleased to hear; well, I don't want to press my opinion on you; at least I am pleased to hear the following:

Of course, the canon here refers to Richard M. Meyer, Albert Bielschowsky, Engel—neo-German senior professors who have written neo-German works on Goethe.10 You see, we are already doing what our times secretly and darkly long for, something that is indeed inevitable—this is a very serious matter. Now please remember some of the first lectures I gave to our groups in these fateful times, where I spoke of a shattering occult experience, namely the perception that the soul of Franz Ferdinand, who was assassinated in Sarajevo, plays a special part in the spiritual world.11 As most of you will remember, I told you his soul has attained cosmic significance, as it were. And now Bahr's novel has been published and people have been buying it for weeks. In it the Archduke Franz Ferdinand is described by a man who had hired himself out, under the guise of a simpleton, as a farmhand by a Salzburg landowner who is the brother of the protagonist Franz. Now this man disguised as a simpleton is so stubborn he has to be whipped to work. At the time of the assassination in Sarajevo, this poor fool behaves in such a way that he gets another thrashing; and imagine, when he reads the news of Franz Ferdinand's assassination in an announcement posted on the church door, this fellow says: “He had to end like this; it could not have been otherwise!” Well, people can't help assuming he was part of the conspiracy even though the murder took place in Sarajevo while the simpleton was in Salzburg. However, such discrepancies don't trouble the people who investigate the matter: Obviously this fellow is one of the Sarajevo conspirators. And since they find books written in Spanish among his possessions, he is evidently a Spanish anarchist. Well, these Spanish books are seized and taken to the district judge, or whatever he is. He, of course, cannot read a word of Spanish but wants to get the case off his docket as quickly as possible after the poor simpleton has been arrested and brought before him. The district judge wants to push this case off on the superior court in Vienna; the people there are to figure out what to do with this Spanish anarchist. After all, the district judge does not want to make a fool of himself; he is an enthusiastic mountain climber and this is perhaps the last fine day of the season, so he wants to get things settled quickly and get going! He understands nothing of the matter. Nevertheless, he is certain of one thing: he is dealing with a Spanish anarchist. Then he remembers that Franz had been in Spain (I told you Bahr himself was there too) and could read Spanish. Franz is to read the book and summarize it for the judge. And so Franz takes the manuscript—and what does he discover? The deepest mysticism. Absolutely nothing to do with anarchism—only profound mysticism! There is actually a great deal that is wonderful and beautiful in the manuscript. Well, according to Franz this simpleton wrote it himself because his very mysticism led him to want to die to the world. Naturally, I do not want to defend this way of proceeding. The simpleton then turns out to be in reality a Spanish infante, a crown prince, and his description fits that of the Archduke Johann who had left the imperial house of Austria to see the world. Franz could not discern the simpleton's Austrian character, but his true identity shines through the disguise, and Franz hits on the idea to say the fellow is a Spanish infante. You can imagine what this means in poor old Salzburg! The people believed they had caught an anarchist and put him into chains—now he turns out to be a Spanish infante! But this man, who knew the heir to the throne, Archduke Ferdinand, what does he say about the latter now after he himself has been unmasked as an infante and a mystic?

“It had to end like this,” that's what he said at the time of the assassination. I have to admit that I was strangely and deeply moved when I read these words a few days ago in Bahr's Himmelfahrt. Just compare what we find in this novel with what has been said here out of the reality of the spiritual world! Try to understand from this how deeply spiritual science is rooted in reality. Try to see that those who are seeking for knowledge, albeit at first only in a groping, tentative way, are really on the same path, that they want to follow this path and that they also arrive at what we are developing here, even down to the details. After all, it is hardly likely that what I said back then could have been divulged to Hermann Bahr by one of our members. But even if that had been the case, he did at any rate not reject it, but accepted it. We do not want to put into practice what is really only some hobby or other. We want to put into practice what is a necessity of our age and a very clear and urgent one at that. And now certain really slanderous things are making themselves felt, and we see that people nowadays are inclined to turn their sympathy to those who spread slander. It is much rarer these days for people to show sympathy for the side that is justified. Instead, precisely where injustice occurs we find people think those who have been wronged must appease and cajole the party who committed the injustice. We find this again and again. Even in our Society we find it again and again. My dear friends, today I do not feel in the mood to go into these things, and in any case that is not the point of my talk. I never mention such things except when it is necessary. But let me conclude by mentioning one more point. In my recently published booklet, I have pointed out that what we are seeking in our spiritual science has been uniform and consistent since the beginning of our work.12 I have also explained that it is indeed slander to talk of any kind of changing sides, of any contradictions to what we did in the early days of our movement. On page 49 you will find the following:

I was referring there to a lecture held in Berlin before the German Section of the Theosophical Society was founded. Continuing along the lines of Goethe, I wanted to create in that lecture the starting point for this new movement not on the basis of Blavatsky and Besant, but based on modern spiritual life, which is independent of those two.14 Yet there are people today who dare to say the name “anthroposophy” was only invented when, as they say, we wanted to break away from the Theosophical Society. As I explained in my book:

Circumstances sometimes bring about favorable situations in karma. Thus, what I wrote a few weeks ago so you can now read it no longer needs rely only on the memory of the few individuals who heard my talk to the Giordano Bruno Society back in 1902, that is, before the German Section was founded. Today I can present documentary evidence. Well, life's funny like that; due to the kindness of one of our members, Fraulein Hübbe-Schleiden, I have recently received the letters I wrote to Dr. Hübbe-Schleiden back then, just before and on the occasion of the founding of the German Section. Now, after his death, those letters were returned to me. The German Section of the Theosophical Society was not founded until October 1902. This particular letter is dated September 16, 1902. There are a few words in this letter I would like to read to you. Forgive me, but I must begin somewhere. There was a lot of talk at that time about connecting with the theosophist Franz Hartmann, who was just then holding a kind of congress.15 I have no intention of saying anything against Franz Hartmann today, but I have to read what I wrote in those days: Friedenau-Berlin, September 16, 1902. Let Hartmann continue to tell his rubbish to his people; in the meantime I want to take our theosophy where I will find people of sound judgment. Once we have a connection to the students [so far we have had only mediocre success with this], we will have gained much. I want to build anew, not patch up old ruins. [That is how the theosophical movement appeared to me then.] This coming winter I hope to teach a course on elementary theosophy in the Theosophical Library. [I did indeed hold this course, and one of the lectures was given during the actual founding of the German Section. The course title is mentioned here, too.] In addition, I plan to teach elsewhere an ongoing course entitled “Anthroposophy or the Connection between Morality, Religion, and Science.” I also hope to be able to present a lecture to the Bruno Society on Bruno's monism and anthroposophy. At this point, these are only plans. In my opinion, that is how we must proceed. That was written on September 16, 1902. Here is the document, my dear friends, that can prove to you these things are not simply claims made after the fact, but they have really happened in this way. It is favorable karma that we are able to show who is right at this moment when so much slander is spread, and will increasingly be spread, about our cause.

|

| 185. From Symptom to Reality in Modern History: Brief Reflections on the Publication of the New Edition of ‘The Philosophy of Freedom’

30 Oct 1918, Dornach Tr. A. H. Parker Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| With this ethical individualism the whole Kantian school, of course, was ranged against me, for the preface to my essay Truth and Science opens with the words: ‘We must go beyond Kant.’ I wanted at that time to draw the attention of my contemporaries to Goetheanism—the Goetheanism of the late nineteenth century however—through the medium of the so-called intellectuals, those who regarded themselves as the intellectual elite. |

| 7 You can imagine the alarm of contemporaries who were gravitating towards total philistinism, when they read this sentence:T3 When Kant apostrophizes duty: ‘Duty! thou sublime and mighty name, thou that dost embrace within thyself nothing pleasing, nothing ingratiating, but dost demand submission, thou that dost establish a law ... before which all inclinations are silent even though they secretly work against it,’ then, out of the consciousness of the free spirit, man replies: ‘Freedom! |

| 15. Rosa Luxemburg (1870–1919). Radical Socialist, worked for overthrow of existing regime. Opposed to war 1914. Author of ‘Spartakus’ letters 1916. |

| 185. From Symptom to Reality in Modern History: Brief Reflections on the Publication of the New Edition of ‘The Philosophy of Freedom’

30 Oct 1918, Dornach Tr. A. H. Parker Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

I have spoken to you from various points of view of the impulses at work in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. You suspect—for I could only draw your attention to a few of these impulses—that there are many others which one can attempt to lay hold of in order to comprehend the course of evolution in our epoch. In my next lectures I propose to speak of the impulses which have been active in the civilized world since the fifteenth century, especially the religious impulses. I will attempt therefore in the three following lectures to give you a kind of history of religions. Today I should like to discuss briefly something which some of you perhaps might find superfluous, but which I am anxious to discuss because it could also be important in one way or another for those who are personally involved in the impulses of the present epoch. I should like to take as my starting point the fact that at a certain moment, I felt that it was necessary to lay hold of the impulses of the present time in the ideal which I put forward in my book The Philosophy of Freedom. The book appeared, as you know, a quarter of a century ago and has just been reprinted. I wrote The Philosophy of Freedom—fully conscious of the exigencies of the time—in the early nineties of the last century. Those who have read the preface which I wrote in 1894 will feel that I was animated by the desire to reflect the needs of the time. In the revised edition of 1918 I placed the original preface of 1894 at the end of the book as a second appendix. Inevitably when a book is re-edited after a quarter of a century circumstances have changed; but for certain reasons I did not wish to suppress anything that could be found in the first edition. As a kind of motto to The Philosophy of Freedom I wrote in the original preface: ‘Truth alone can give us assurance in developing our individual powers. Whoever is tormented by doubts finds his powers emasculated. In a world that is an enigma to him he can find no goal for his creative energies.’ ‘This book does not claim to point the only possible way to truth, it seeks to describe the path taken by one who sets store upon the truth.’ I had been only a short time in Weimar when I began to write The Philosophy of Freedom. For some years I had carried the main outlines in my head. In all I spent seven years in Weimar. The complete plan of my book can be found in the last chapter of my doctoral dissertation, Truth and Science. But in the text which I presented for my doctorate I omitted of course this last chapter. The fundamental idea of The Philosophy of Freedom had taken shape when I was studying Goethe's Weltanschauung which had occupied my attention for many years. As a result of my Goethe studies and my publications on the subject of Goethe's Weltanschauung I was invited to come to Weimar and collaborate in editing the Weimar edition of Goethe's works, the Grand Duchess Sophie edition as it was called. The Goethe archives founded by the Grand Duchess began publication at the end of the eighties. You will forgive me if I mention a few personal details, for, as I have said, I should like to describe my personal involvement in the impulses of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. In the nineties of the last century in Weimar one could observe the interweaving of two streams—the healthy traditions of a mature, impressive and rich culture associated with what I should like to call Goetheanism, and the traditional Goetheanism in Weimar which at that time was coloured by the heritage of Liszt. And also making its influence felt—since Weimar through its academy of art has always been an art centre—was what might well have provided important impulses of a far-reaching nature if it had not been submerged by something else. For the old, what belongs to the past, can only continue to develop fruitfully if it is permeated and fertilized by the new. Alongside the Goetheanism—which survived in a somewhat petrified form in the Goethe archives, (but that was of no consequence, it could be rejuvenated, and personally I always saw it as a living force)—a modern spirit invaded the sphere of art. The painters living in Weimar were all influenced by modern trends. In those with whom I was closely associated one could observe the profound influence of the new artistic impulse represented by Count Leopold von Kalkreuth,1 who at that time, for all too brief a period, had been a powerful seminal force in the artistic life of Weimar. In the Weimar theatre also a sound and excellent tradition still survived, though marred occasionally by philistinism. Weimer was a centre, a focal point where many and various cultural streams could meet. In addition, there was the activity of the Goethe archives which were later enlarged and became the Goethe-Schiller archives. In spite of the dry philological approach which lies at the root of the work of archives, and reflects the spirit of the time and especially of the outlook of Scherer,2 an active interest on the more positive impulses of the modern epoch was apparent, because the Goethe archives became the magnet for international scholars of repute. They came from Russia, Norway, Holland, Italy, England, France and America and though many did not escape the philistinism of the age it was possible nonetheless to detect amongst this gathering of international scholars in Weimar, especially in the nineties, signs of more positive forces. I still vividly recall the eccentric behaviour of an American professorT1 who was engaged on a detailed study of Faust. I still see him sitting crosslegged on the floor because he found it convenient to sit next to the bookshelf where he could immediately put his hand on the reference books he needed without having to return continually to his chair. I remember also the gruff Treitschke3 whom I once met at lunch and who wanted to know where I came from. (Since he was deaf one had to write everything down on slips of paper.) When I replied that I came from Austria he promptly retorted, characterizing the Austrians in his inimitable fashion: well, the Austrians are either extremely clever people or scoundrels! And so one could take one's choice; one could opt for the one or the other. I could quote you countless examples of the influence of the international element upon the activities in Weimar. One also learned much from the fact that people also came to Weimar in order to see what had survived of the Goethe era. Other visitors came to Weimar who excited a lively interest for the way in which they approached Goetheanism, etcetera. I need only mention Richard Strauss4 who first made his name in Weimar and whose compositions deteriorated rather than improved with time. But at that time he belonged to those elements who provided a delightful introduction to the modern trends in music. In his youth Richard Strauss was a man of many interests and I still recall with affection his frequent visits to the archives and the occasion when he unearthed one of the striking aphorisms to be found in Goethe's conversations with his contemporaries. The conversations have been edited by Waldemar Freiherr von Biedermann5 and contain veritable pearls of wisdom. I mention these details in order to depict the milieu of Weimar at that time in so far as I was associated with it. A distinguished figure, a living embodiment of the best traditions of the classical age of Weimar, quite apart from his princely origin, was a frequent visitor to the archives. It was the Grand Duke Karl Alexander whose essentially human qualities inspired affection and respect. He was the survivor of a living tradition for he was born in 1818 and had therefore spent the fourteen years of his childhood and youth in Weimar as a contemporary of Goethe. He was a personality of extraordinary charm. And in addition to the Duke one had also the greatest admiration for the Grand Duchess Sophie of the house of Orange who made herself responsible for the posthumous works of Goethe and attended to all the details necessary for their preservation. That in later years a former finance minister was appointed head of the Goethe Society certainly did not meet with approval in Weimar. And I believe that a considerable number of those who were by no means philistine and who were associated in the days of Karl Alexander with what is called Goetheanism would have been delighted to learn, in jest of course, that perhaps after all there was something symptomatic in the Christian name of the former finance minister who became president of the Goethe Society. He rejoiced in the Christian name of Kreuzwendedich.6 I wrote The Philosophy of Freedom when I was deeply involved in this milieu and I feel certain that it expressed a necessary impulse of our time. I say this, not out of presumption, but in order to characterize what I wanted to achieve and still wish to achieve with the publication of this book. I wrote The Philosophy of Freedom in order to give mankind a clear picture of the idea of freedom, of the impulse of freedom which must be the fundamental impulse of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch (and which must be developed out of the other fragmentary impulses of various kinds.) To this end it was necessary first of all to establish the impulse of freedom on a firm scientific basis. Therefore the first section of the book was entitled ‘Knowledge of Freedom.’ Many, of course, have found this section somewhat repugnant and unpalatable, for they had to accept the idea that the impulse of freedom was firmly rooted in strictly scientific considerations based upon freedom of thought, and not in the tendency to scientific monism which is prevalent today. This section, ‘Knowledge of Freedom,’ has perhaps a polemical character which is explained by the intellectual climate at that time. I had to deal with the philosophy of the nineteenth century and its Weltanschauung. I wanted to demonstrate that the concept of freedom is a universal concept, that only he can understand and truly feel what freedom is who perceives that the human soul is the scene not only of terrestrial forces, but that the whole cosmic process streams through the soul of man and can be apprehended in the soul of man. Only when man opens himself to this cosmic process, when he consciously experiences it in his inner life, when he recognizes that his inner life is of a cosmic nature will it be possible to arrive at a philosophy of freedom. He who follows the trend of modern scientific teaching and allows his thinking to be determined solely by sense perception cannot arrive at a philosophy of freedom. The tragedy of our time is that students in our universities are taught to harness their thinking only to the sensible world. In consequence we are involuntarily caught up in an age that is more or less helpless in face of ethical, social and political questions. For a thinking that is tied to the apron strings of sense perception alone will never be able to achieve inner freedom so that it can rise to the level of intuitions, to which it must rise if it is to play an active part in human affairs. The impulse of freedom has therefore been positively stifled by a thinking that is conditioned in this way. The first thing that my contemporaries found unpalatable in my book The Philosophy of Freedom was this: they would have to be prepared first of all to fight their way through to a knowledge of freedom by self-disciplined thinking. The second, longer section of the book deals with the reality of freedom. I was concerned to show how freedom must find expression in external life, how it can become a real driving force of human action and social life. I wanted to show how man can arrive at the stage where he feels that he really acts as a free being. And it seems to me that what I wrote twenty years ago could well be understood by mankind today in view of present circumstances. What I had advocated first of all was an ethical individualism. I had to show that man can never become a free being unless his actions have their source in those ideas which are rooted in the intuitions of the single individual. This ethical individualism only recognized as the final goal of man's moral development what is called the free spirit which struggles free of the constraint of natural laws and the constraint of all conventional moral norms, which is confident that in an age when evil tendencies are increasing, man can, if he rises to intuitions, transmute these evil tendencies into that which, for the Consciousness Soul, is destined to become the principle of the good, that which is befitting the dignity of man. I wrote therefore at that time:

I envisaged the idea of a free community life such as I described to you recently from a different angle—a free community life in which not only the individual claims freedom for himself, but in which, through the reciprocal relationship of men in their social life, freedom as impulse of this life can be realized. And so I unhesitatingly wrote at that time:

With this ethical individualism the whole Kantian school, of course, was ranged against me, for the preface to my essay Truth and Science opens with the words: ‘We must go beyond Kant.’ I wanted at that time to draw the attention of my contemporaries to Goetheanism—the Goetheanism of the late nineteenth century however—through the medium of the so-called intellectuals, those who regarded themselves as the intellectual elite. I met with little success. And this is shown by the articleT2 which I recently wrote in the Reich and especially by my relations to Eduard von Hartmann.7 You can imagine the alarm of contemporaries who were gravitating towards total philistinism, when they read this sentence:T3 When Kant apostrophizes duty: