| 65. From Central European Intellectual Life: How Are the Eternal Powers of the Human Soul Investigated?

11 Feb 1916, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| And in general it is well known today, even in wider circles, what the whole intimate spiritual process of development from Kant up through Hegel means for the spiritual life of humanity in general. However, when something like this is mentioned, I do not want to fail to add that the great thinkers who come into question here are never really properly appreciated, if one is still even remotely on the ground that leads one to accept as dogma what a person expresses as a truth that he has recognized or, let us say better, meant. |

| Karl Rosenkranz wrote in 1863: “Our contemporary philosophy returns to Kant so often because it was the starting point of our great philosophical epoch. However, it should not just take up those pages of Kant that are convenient for it, but should seek to understand him in his totality. |

| What did these German idealists achieve, these much-mocked German idealists? Hegel – perhaps I may, without seeming immodest, draw attention to the accounts I have given of Hegel in 'Riddles of Philosophy', in the new edition of my 'World and Life Views in the Nineteenth Century'. — Hegel tried to grasp everything that lives and moves in the world in pure thought, so to speak, to extract the entire network of thought from the abundance of phenomena, facts and things in the world. |

| 65. From Central European Intellectual Life: How Are the Eternal Powers of the Human Soul Investigated?

11 Feb 1916, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

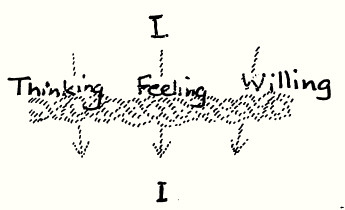

In the course of my lectures here I have often spoken about the great period of spiritual development that may be called the time of German idealism. And in general it is well known today, even in wider circles, what the whole intimate spiritual process of development from Kant up through Hegel means for the spiritual life of humanity in general. However, when something like this is mentioned, I do not want to fail to add that the great thinkers who come into question here are never really properly appreciated, if one is still even remotely on the ground that leads one to accept as dogma what a person expresses as a truth that he has recognized or, let us say better, meant. One can go beyond this; then one is in a position to completely abandon the formulation of any human opinion, any human construct. But to see the way in which a person has sought truth, how, as it were, the truth instinct lived in him, the how of the search for truth, that is what remains as the eternally interesting thing about the figures of, in particular, the thinkers of the past. And in particular, what remains with respect to the thinkers of German idealism, among many other things, is what one can feel, so to speak, again and again when one delves into them: that they have achieved a certain ability to orient themselves with respect to what man can call truth, truth research, world view, that they knew, as it were, how impossible it is to orient oneself in the world if one relies only on taking in the impressions of the world, letting them take effect on one, in order to be at their mercy, like a plaything, so to speak. Above all, these thinkers knew that what can decide the sense of truth, the sense of worldview, must be sought in the depths of the human soul itself, since it must be brought up. Karl Rosenkranz was a less recognized latecomer to these great thinkers, who also became less well known. And this Karl Rosenkranz tried in the 1860s of the last century to review in his mind's eye what had developed as an understanding of the human soul and its powers since German idealism through the influences of a more scientific way of thinking. I would like to read to you the introduction to today's reflections on how Karl Rosenkranz, the well-educated, subtle Hegelian, has commented on this soul-searching of the thirty years that followed the period of German idealism. Karl Rosenkranz wrote in 1863: “Our contemporary philosophy returns to Kant so often because it was the starting point of our great philosophical epoch. However, it should not just take up those pages of Kant that are convenient for it, but should seek to understand him in his totality. Then it would also understand that one can go back to Kant as the founder of our German philosophy and as an ideal of philosophical endeavor, but not to stop at him. The modesty of science consists in recognizing the limits that one recognizes for oneself, and not in flying over them with a semblance of knowledge. But it does not consist in inflating one's pride with the humility of an uncritical lack of knowledge or weak doubts and proclaiming points of view that history has overcome as absolute because one could not hold on to other, self-made ones, our philosophy of today is above all inductions, above all physical and physiological, psychological and aesthetic, political and historical micrology of the concept of the absolute” - and by ‘absolute’ Karl Rosenkranz understands the philosophy of the spirit - ”without which real philosophy cannot exist, has been lost. For this concept, all observation, all discovery through telescopes and microscopes, all calculation comes to an end; it can only be conceived.It can be said of these thinkers that they had a sense of the productivity of thought; they had confidence in the power of thought, which, by intensifying itself, can find within itself that source from which that which is able to enlighten the world bubbles forth. And they knew that no matter how much external methods and instruments of natural science are perfected, that which truly quickens the spirit in man is not to be found in the realm that can be conquered by external methods and instruments. I have often said here that the spiritual science that wants to be represented in these considerations cannot, for example, be in any kind of contradiction with the scientific world view of our time. On the contrary, it is in complete harmony with every legitimate formulation of the scientific world view. This spiritual science does not want to be some kind of new religion; it wants to be a genuine, true continuation of natural science, or rather of the natural scientific way of thinking. And one can say that for anyone who observes the development of science over the time that has passed since Karl Rosenkranz wrote what you have read, it offers impulses in every field that lead directly to this spiritual science, if one is really able to engage with it. And this natural science offers such impulses precisely when one engages with it where it itself attempts to extend its observations in such a way that they lead to the realm of the spiritual. Now there is a science that is particularly suited to making it clear where natural science is leading when it wants to approach the realm of the spiritual in a way that is right for it and its methods. This science is called, with a somewhat cumbersome word, psychophysiology, and as a rule we are dealing with people in the field of psychophysiology who thoroughly understand how to apply the scientific methods that can be acquired in the various scientific workshops. Now there are already psychological laboratories, and in these psycho-physiologists we also have people who can be trusted to be familiar with the scientific way of thinking, with the way this scientific way of thinking relates to the world and its phenomena. We can now begin to understand what has been achieved in this psycho-physiological field. If you want to educate yourself in a short time, I advise you to take Theodor Ziehen's “Physiological Psychology”, because it gives a quick overview and because it is basically, even the older editions, at the complete level of today's research in this field. But you could just as easily look for this physiological psychology in some other author. If you now engage with this physiological psychology, you get an idea of how the person who uses scientific methods in the sense of the scientific way of thinking approaches the human being in order to examine that which I would say, clinically and in the sense of a physical laboratory, or a psychological laboratory for all I care, can be investigated in a person, what can be investigated in a person by the person expressing themselves spiritually and psychologically. And it may be said that even if what is science in this field today often represents an ideal, the various directions towards this ideal can already be seen everywhere, and anyone who is not prejudiced will want to fully recognize the great merits of the individual research in this field. Naturally, in the sense of today's scientific thinking, these researchers are endeavoring to seek the physical, the bodily, in everything that takes place in the human being in a spiritual and mental way, to seek those processes in the human body that take place while something spiritual and mental is happening in us. And in this field, as I said, paths have already been opened. And there one experiences something very peculiar at first. And at this moment, when I try to describe to you what one experiences, I emphasize that I initially place myself completely on the ground of what is justified in this field of science. One experiences something remarkable; one experiences that researchers in this field can investigate what we call the life of human ideas in a truly magnificent way. In our mental life, ideas are stimulated by external impressions that we can perceive. These ideas join together and separate from one another. This is what our soul life consists of, insofar as it is a life of ideas: we form inner images of the impressions from the outside world, and these images group themselves. This is a large part of our soul life. Now the psychophysiologist can follow how the ideas socialize inwardly, how they form, and he can follow the physical processes everywhere in such a way that he always sees: On the one hand, there is the mental process in the life of ideas, and on the other hand, there is the physical process. And it will never be possible, if one is only unprejudiced, to discover a real soul life in a person to whom such a physical counterpart cannot be shown, even if, as I said, proof is still a scientific ideal today. And so it is extraordinarily appealing, extraordinarily interesting, to follow in the human thinking apparatus — now really conceived as a thinking apparatus in the proper sense, in so far as it is bodily-physically constructed — how everything happens when man inwardly experiences his imaginative life. And it is precisely in this respect that the book by Theodor Ziehen contains something extraordinarily significant, yes, I would even say scientifically extraordinarily reasonable. But now for the other peculiarity. The moment one has to speak of feeling and especially of will in the life of the soul, this psychophysiology not only fails, I might say instinctively, but with the truly modern psychophysiologist it even fails quite consciously. And you can see in Ziehen's book how, at the moment when one is supposed to talk about feeling and will, he does not get involved in it at all, continuing the investigations up to that point. How does he speak of feelings? Well, he says it bluntly: the natural scientist does not speak of an independent emotional life in man, but rather, in that one gets impressions from the outside - these impressions are stronger or weaker, they have these or other characteristics - a certain “feeling tone” is formed afterwards. He speaks only of feeling tone, and so, to a certain extent, of a way in which the sensation sinks in first, and then the image, into the soul life. That is to say, the psychophysiologist loses his breath — forgive the trivial expression, but it has to be said — at the moment when he is to pass from the life of images and their parallelization in the psychophysiological mechanism to the life of feeling. And if he is as honest as Theodor Ziehen, he admits this by simply saying what he does: In the past, people still thought naively, speaking of three soul powers, of a thinking or imagining, of a feeling, of a willing. But for the natural scientist, there can be no question of a feeling, of a real soul-being that lives in pleasure and pain like a real one. These are all only tones in which there are shades of what the life of perception and feeling is. So the scientist consciously, not just unconsciously, loses his breath; consciously he stops breathing scientifically. And this occurs to an even greater extent when we speak of the third soul power, the will. In psychophysiology, we find nothing about the will except what is expressed: it cannot be found, it is impossible to find it, especially with the means of a rational, scientific way of thinking. It is an interesting and extraordinarily important result that must be noted and taken seriously. The natural scientist can say: Well, I have this scientific view; with this scientific view, I find, so to speak, the thinking apparatus, the mental apparatus for the soul life, insofar as it takes place in the mental life; I do not concern myself with the other! The scientific researcher can rightly say that. The amateur world-viewer, who likes to give himself the grandiose title of monist, will not easily notice that the breath has been suppressed quite arbitrarily, but he will believe that by passing over from the life of thinking into the life of feeling and of will, he continues to breathe, and he will see in the life of feeling and of will only a kind of product of the development of the life of thinking. And so it is only natural that we arrive at the strange conclusion that people like Theodor Ziehen say: the will is not present at all, the will is a pure invention. What do we actually have when we speak of the will in any of our activities? Well, as people think in a trivial way of looking at things, will is already present when I just move my hand. But first of all I have the impression, I feel a mental impression that causes me to move my hand. And then my mental life passes over to the observation of my moving hand, which I may also perceive with senses other than the eye. But I have only a sum of ideas. I simply go from the impressions to the ideas of movement. That is, I am actually just constantly watching myself. And if one wants to be a part of these confrontations - I now say: of the dilettantish monism, of the world view - then one should feel how one is eradicating precisely that which is the most intimate inner experience — the life of feeling and the life of will — when man is made into what he must not be made into, when natural science is not left as natural science but is turned into a Weltanschhauung in an amateurish way. For the spiritual researcher, however, the path of the natural scientist is of extraordinary importance, because this path has already been followed to such an extent that it clearly shows how far the scientific method of research can go. A clear boundary can already be seen. Particularly when one delves into the works of those thinkers who preceded the natural science direction, the thinkers of German idealism, one finds in them a clear awareness that the higher secrets of the world must be investigated by immersing oneself in the human soul. These thinkers were even ridiculed for wanting to unravel these secrets of the world, as it were, and develop them all from the human soul. But it is also characteristic of what these thinkers actually achieved, and it is particularly characteristic for the observer to compare what the German idealists achieved and what was then achieved by the scientific way of thinking and research. What did these German idealists achieve, these much-mocked German idealists? Hegel – perhaps I may, without seeming immodest, draw attention to the accounts I have given of Hegel in 'Riddles of Philosophy', in the new edition of my 'World and Life Views in the Nineteenth Century'. — Hegel tried to grasp everything that lives and moves in the world in pure thought, so to speak, to extract the entire network of thought from the abundance of phenomena, facts and things in the world. But one must admit, despite all objections, that this network of thoughts cannot be gained through contemplation, cannot be gained through external observation. For one tries only once to let the outside world have its effect on oneself, not to produce within oneself the source of thinking, which makes the soul active – nothing will come out of thoughts! But if one does not want to apply one's thoughts to the world, if one denies that thoughts can have any meaning, because they necessarily have to arise, one might say, out of the human soul, then one would have to renounce any mental discussion of the world. And not even Haeckel would want to do that! By handling thought in general, one lives entirely in thought, in the awareness that thought expresses something that has significance for the world itself. The Hegelians were only aware of the fact that thought is an inner experience and, despite being an inner experience, has objective significance for the existence of the world. But if we now take a closer look at what the whole idealistic way of thinking has achieved – I will now say: through thought and in thought, for whose way of observation it has had such practice – we can hardly expect anyone today, for example, to go through Hegel's writings for what I am about to mention. But if someone does so, they come to the following: Hegel is a master in the handling of thought, which is not influenced at all by any sensual impression from outside; he is a master in the development of one thought out of another, so that one has a whole living organism of thoughts in his – well, let us use the terrible word – system. But let us take a closer look at this Hegel with all his thoughts. We can, I would say, divide him into two parts. The first part is where he develops thoughts. But all these thoughts relate to that which is externally sensual in the world. They are only, I might say, internal reflections of that which is externally sensual in the world. And the second part relates to the historical development of humanity, to social and state concepts, and it culminates in what the human being can develop in terms of perceptions, thoughts and ideas, which then express themselves emotionally as religion, visually as art, and in terms of ideas as science. So that is what Hegel wants to achieve by bringing the thought to life within him; he regards this as the innermost source of world existence, and he pursues it to the flowering of development in religion, in art, in science. But religion, art and science - are they not in turn merely something that has a meaning for the outer physical world? Or could anyone imagine that the content of religious belief could somehow have a meaning for a spiritual world? Or could he even believe that art, which must speak through the sensual tool, can have any meaning - an immediate meaning, of course - within the spiritual world? Or our science? Well, we will talk about that later. Hegel does find the thought, but it is only a thought that, though it lives and moves within, only reflects the external. This thought cannot come to life in any world that could exist except the sensual-physical world. A spiritual world does not come about through Hegelianism, but only the spiritual image of the physical world. And science? Precisely the science that followed, which is to be taken very seriously, now examines this thought, this thought life of the human being, and finds: it comes to it, in that it finds the thinking apparatus in man, as it were, for the thought life, right up to the feeling and will life; there it has to stop. If we now really hold the two together, must we not assume that, on the one hand, Hegelianism, for example, or in general that idealistic world view of which we have spoken, really did strive into a spiritual world — but found more than merely the spiritual counter-image of what is not spiritual? On the other hand, must we not say: So could not this Hegelianism, this idealism gain access to that which it must admit to its existence because thought could have no meaning as purely spiritual in the face of reality if there were not a spiritual world? It is interesting that everything that German idealism has just produced in terms of thought flows from the spiritual world, but that there is nothing in it but what the scientific way of thinking can assume as its thinking apparatus. But in other words, if one really wants to enter the spiritual world, and if one wants to enter it in such a way that one can stand before natural science, then one must enter the realm of feeling and will, but not in the sense in which one feels and wills in ordinary life, but in the way the natural scientist enters the world of nature. Now, Now, from other points of view, I have often indicated here the ways in which one can truly enter the spiritual world while remaining on the firm ground of natural science. Today, through this historical overview, I only wanted to show how, through the thinking that one usually knows, even when it is driven to such purity, to such cold, sober, icy purity as in German idealism, one can indeed come to the conviction that there is a spiritual world, for this thinking is not won by an outer impression, it must itself come from the spiritual world. But one cannot enter the spiritual world through this thinking. Why can one not enter the spiritual world through this thinking? As I said, I have often treated this question here from different points of view. Today, I would like to approach it again from a different point of view. We cannot enter into the spiritual world because in recent times we have increasingly tried to expunge from our thinking everything that the natural scientist no longer finds in it. This means that we have tried to expunge feeling and will from our thinking. To see that this is so, one has only to consider the basis of the great, most important significance of the natural scientific way of thinking. It rests on the fact that, when one goes about observing nature, one must, I might say, kill and paralyze all soul-life within oneself. Whether he is observing things and their facts or experimenting, the naturalist will strictly exclude everything that comes from his feelings and everything that comes from his will. He will never allow what he feels towards things to interfere with what he wants to express about what he has observed, what he would prefer to be the truth, so to speak, rather than what the things themselves say. It may be said that the scientific development of modern times, which goes back three to four centuries, has really provided a good training in what is called scientific objectivity. Selfless, in the good sense of scientific and in many ways ennobling, would be the right description for human life, which may be called the elimination of the self in the face of the language of natural phenomena. Great progress has been made in this respect. And in psychophysiology, we have even gone so far as to think in such a way that we no longer find feeling and will in thinking. That is to say, what was a method of research has already become practical, has already come to life. We should switch off the soul when observing nature. One has learned to exclude it in such a way that one can no longer find it in the whole field of observation. What remains unconscious in our thinking, when we give ourselves completely passively to the external world, as must be the ideal of the natural scientist — when he also sets up the experiments, it must be his ideal — unconscious in thinking remains that which can be called: will. It is precisely the endeavor to eliminate the will from thinking when one conducts research in relation to nature in today's sense. It remains unconscious because one always needs a will when one adds one thought to another – they do not do it themselves, after all – or when one separates one thought from another. Nevertheless, it remains the ideal of natural science to suppress as much as possible of this will that lies in the life of thought. It is therefore quite natural that the scientific ideal, I might say, makes the inner life of the soul die away for the sake of human habit. And it is much more due to this — and I expressly say: justified — scientific ideal that the exclusion of the soul has been able to take place as it has, that one must precisely disregard everything of the soul, exclude everything of the soul, if one wants to follow nature faithfully in the sense of today's natural science. But there is another side to this. And it is extremely important to consider this other side. What is it that man seeks when he seeks knowledge? Well, first of all, when he seeks knowledge, he seeks something that is true apart from him. For if he did not think of truth as something separate from himself, he could create it for himself in every moment. That he does not want to do that is readily admitted. So when man seeks an ideal of knowledge, he seeks to bring to life within himself something to which he contributes as little as possible. Just consider how opposed people are today to self-made concepts, especially in the scientific field! So one strives to have something in one's knowledge that, I might say, reflects external reality, but which has just as little to do with this external reality as a mirror image has with what is reflected. Just as the mirror image cannot change what is reflected, so too should what comes to life in the soul as the content of knowledge not change what takes place outside. But then one must eliminate all soul activity, for then the soul can have no significance for knowledge. And when one strives so hard to eliminate the soul, it is not surprising that in this field the soul cannot be found. Therefore spiritual research must begin precisely where the scientific way of thinking must end. That is to say, thought must be sought in what the will is in thought. And this happens in everything that the soul has to undergo in those inner experiments, as has been mentioned here often enough, everything that the soul has to undergo in inwardly strengthening and intensifying the thinking, so that the will working in the thinking no longer remains unconscious to the thinking , but becomes conscious of this will, so that man really comes to experience himself in such a way that he, as it were, lives and moves in thinking, is directly involved in the life and movement of the images themselves and now no longer looks at the images themselves, but at what he does. And in this, the human being must become more and more, I would say, a technician, acquiring more and more inner practice, living into what happens through himself as the life of the imagination unfolds. And everything that the human being discovers in himself otherwise remains between the lines of life. It always lives in the human being, but it does not rise up into consciousness, the will is suppressed in the life of the imagination. When one develops such inner vitality, such inner liveliness, that one not only has images but enters with one's experience into this surging and ebbing, into this becoming and passing away of the images, and when one can take this so far you no longer bring the content of the ideas into your attention, but only this activity, then you are on the way to experiencing the will in the world of ideas, to really experiencing something in the world of ideas that you otherwise do not experience in life. This means that, if we are to remain true to what the scientific way of thinking itself leads to, we must go completely beyond the way in which natural science conducts research. In a sense, we must not take what natural science investigates, but we must observe ourselves doing natural science. And what is practiced in this way, and what can only lead to success if it is practiced for years – after all, all scientific results are only achieved through long work – what is achieved in this way is a living into a consciousness in a completely different world. What is achieved can only be experienced; it can be described, but it cannot be shown externally, it can only be experienced. For what is achieved in practice is, I would say, what the scientific way of thinking already points to. This scientific way of thinking tells us: If I go on my way, I come to a limit. I go as far as I can still find something human. There I do not find a world in which there is will and feeling. But this world, where feeling and will are discovered just as objectively as plants and minerals are otherwise discovered here, this world can be found if one can make this inner experience of the ideas effective in the soul between the lines of the rest of the imaginative life. Only now one experiences that which one can otherwise only sense. Today, the natural scientist will already be more or less inclined to say: It is blind superstition when someone claims that what is known in the physical world as thinking, as imagining, can somehow take place without a thinking apparatus, without a brain, without a nervous system. The natural scientist asserts this on the basis of his theory. One could easily believe — and laymen in relation to this spiritual research do believe — that spiritual research must disprove the scientist's assertion. This is not the case. On the contrary, in as far as this assertion can be well derived from the facts of natural science, the spiritual researcher is standing firmly on the ground of natural research in this field. Only he actually experiences what the scientist deals with on the basis of theory. For when one experiences this weaving and living, as I have indicated, in the world of ideas, then one knows: now one has arrived at the point where the thinking apparatus can give one nothing more. All thinking one has done so far is bound to the thinking apparatus. Now one has arrived at that inner experience, that weaving, that is no longer bound to the thinking apparatus. But at the same time, one has arrived at something that, when stated, initially seems outlandish compared to the usual ways of thinking in the present day. But everything that has ever appeared in science and had to be incorporated into the intellectual development of the world was outlandish at first and then taken for granted. At first it seems strange, but it is a truth. By awakening this inner life and activity, one leaves the world one experiences between birth or, let us say, between conception and death here on earth. One leaves it and enters a world that one cannot experience in the physical body. Rather, one is in the world to which one belonged before birth or, let us say, when the spiritual soul was just beginning to adapt to what it had been given of the physical by the hereditary current, or what it gave itself. We are dealing with forces that do not use the thinking apparatus to develop an imaginative life, but forces that first form and fully develop the thinking apparatus only in the course of life after birth. For the inner nervous life, the inner nervous web, is only chiseled out and plasticized in the course of the first years and long beyond, when we have entered our physical existence. One is in the forces that shape the human being inwardly as plastic forces, so that he can become what he is; so that he is a creature of his spiritual and soul self. But one must not believe that one should not take this existence to the full, and I now mean, in practical earnest. For you see, out of a natural weakness of human nature, the spiritual researcher will always be asked to recognize first of all that which is the immediate present, which is, I might say, more the confused spiritual of the physical-sensual world. Here in the physical-sensual world, one gets to know things with the senses. But that which has formed these senses themselves, that which underlies these senses as the architect, that one gets to know, if one knows how to transport oneself out of the physical lifetime into the time that preceded the physical life and will follow the physical life, in the way it has been described. One gets to know a world with which this world here has basically no similarity. And in what I have described as the inner experience of the thinking activity instead of the thoughts, a real spiritual world opens up, in which the world really opens up, in which the human being is with other spirit beings when he is not embodied in the physical body. This world is just as concrete and just as vividly inwardly visualized as the external, real, physical world. Only, as I have already explained here, something else must be added. We see that in the path taken by thinking, everything comes down to strengthening, to intensifying thinking, to an inward powerful experience of thinking. So it comes down to the fact that ultimately, before this inward powerful experience, the content of thinking lies, of course, only in consciousness, and the soul can truly experience itself in the weaving of the imagination. But there must be added, as a parallel experiment, I might say, to our life a culture, a development of the will element, of the will and feeling element. Now, while everything depends on inwardly strengthening this thinking, I might say, on becoming it, in the development of thinking into the spiritual world, everything in the other development of the will depends on develop the opposite qualities: calmness of soul, composure; that one becomes capable of confronting what we call our actions, the unfoldings of our will, in the way one can learn from the study of nature. Not that one becomes a cold person, sucked dry like a lemon; one does not become that. On the contrary, everything that otherwise often remains unused by the deeper-lying 'temperament and affects comes to the soul when it is subjected to the observation that comes from composure and calmness. If one first trains oneself, then trains, as Goethe, for example, trained himself in observing the types of plants and animals, if one first trains oneself to observe the outside world in such a way that one really practices self-denial and then does not transfer this pedantically and theoretically to self-observation, but acquire the appropriate reinforcement and then turn the view that you have sharpened on nature back to yourself, then you will find the possibility to observe your own soul life, insofar as it develops from will and from feeling, from sympathies and antipathies and flows into actions as will impulses. you gain the opportunity to observe this life of the soul in such a way that you now do not stand beside yourself in the figurative sense, but really stand beside yourself and consciously look at this person, as one can look at another person, or, as I said eight days ago: as one also bears one's own life of yesterday in one's memory, because one also does not change it. One looks at this by bringing an awareness out of the ordinary awareness. You really come to the possibility of saying to yourself: you keep still within the otherwise flowing stream of soul experiences that arise from feeling and will. By keeping still yourself, by attaining complete inner peace, by really standing still, not going along with the affects, not going along with the will impulses and so on, but just standing still with the soul, you naturally duplicate yourself. For it would be a bad thing if, as I said, one became an expressionless human being, if one did not remain completely within the whole of the temperament of the person who goes further; if one could not live with all his feelings and temperaments. But the other person, whom I called the spectator in the previous lecture, remains standing: This makes him stay there, and one's own soul life really begins to move around him, as the planets move around the sun. All a spiritual process! It is difficult to learn to stand still, but one cannot observe the life of the will if one cannot stand still. If one goes with the flow of the life of the will, one is always in the middle of everything. When you stop, you can observe it because, to use a crude expression, it rubs against you as it passes by and moves away from you. But all this does not have to remain theory – remaining in theory is of no use – but it must really become an inner practice of life. Then it is not an image, but reality, that a second person emerges from the first and unites with it. Just as under certain conditions oxygen unites with hydrogen, so too, as I have just described, the second person unites with the person who has been seized, who lives and weaves with the life of ideas. And this is now really a person who lives outside of ideas. While in the past one discovered in the images a spiritual, concrete world in which there are spiritual beings, just as there are animals and minerals here on earth, when what I have just described is added, through the second person being at rest in the face of the will impulses, one discovers in fact that that which out of this spiritual world always develops into the physical world, always finds its way into the physical world; that which in the spiritual world always strives to find physical expression either through union with the physical, as is the case with human or animal life, or through direct manifestation, as is the case, for example, with crystals. And now what is often regarded as madness by people today is beginning to be experienced inwardly; what Lessing said, what he expresses so beautifully in his “Education of the Human Race”, is now beginning to be experienced. Now the human being knows – by having achieved this inner stillness in the face of the impulses of the will – that something lives in him that once wanted to unite with this body because it developed such powers earlier, as it is now developing again, as they are now showing themselves, and as they live in this body, just as the germ lives in the plant. And just as the germ in the plant is the source of a new plant, so that which is now being grasped in man is the source of a future life, which will be grasped when the time between death and birth or a new conception is completed. The repeated lives on earth become a thought, which is a real continuation of the scientific idea of development. And only someone who cannot take his thinking far enough to see that what lives in man really lives in this man, insofar as he is a physical being, as the plant germ lives physically in the plant for a new plant, that a spiritual-soul man lives, that this spiritual-soul man, I would like to say, , has its cover in the physical body, but the germinal development is for a following earth life. Only the one who cannot think sharply enough, who cannot really think out the thoughts that are already there today and that are also used in natural science, can escape the necessity of searching for these eternal powers of the human soul from the natural scientific way of thinking. of the human soul, which are sought entirely scientifically, by first simply, I would say seriously, taking science at its word: that it must stand still in the face of emotional and will life, but then it will reach precisely into this emotional and will life, by seeking it where it would otherwise remain unconscious: in thinking. And on the other hand, thinking is sought out where it otherwise hides; for in the will, where it flows in, this thinking hides. But precisely because this natural science is taken very seriously, these eternal powers of the human soul are discovered, which cannot be reached by observing man in the abstract and saying, “There must be something eternal in this man too”; for it is not so that one can reach this eternal something by extending the lines backwards and forwards as one likes, because it is not so. These lines are not straight, continuous lines. Just as, when I have a plant in front of me, this plant forms the germ and in the germ is the disposition for the new plant, I have to go from plant to plant, adding one link to the next. In the same way, when we achieve this second thing, calmness in the life of the will, I would say that we find another memory that lights up, the memory of earlier earthly lives. And in the same way, when we achieve this second thing – peace in the life of the will – I would say that we find, as if a memory were lighting up, a review of earlier earthly lives. Admittedly, most people will give up quite early on if they are to undertake research that is not as convenient as the study of the natural world. There you have the object or the experiment in front of you, you surrender passively, you observe. No, the spiritual world cannot be observed in this way! The spiritual world can only be grasped if you really change your inner being, bring it to life for the spiritual world. For the physical world, we have hands; for the spiritual world, we must first develop the ability to grasp ideas, which, like inner hands, like inner grasping organs, can grasp the spiritual world. The researcher is always active and engaged when he is truly immersed in the spiritual world. But now I said, one usually stops early, one will not easily lead the way, which is a laborious one, to a successful end. Indeed, the desires that can be fulfilled in this exploration of the eternal powers of the human soul, these desires are certainly shared by many people – because it is not true, “beautiful”, “infinitely beautiful” it is to look back on past lives on earth! You experience it again and again, how people find it beautiful. Those who have had a little taste of what spiritual research is, and then call themselves spiritual researchers, we experience it again and again with them, that they look back on their previous lives on earth. These earlier lives are, of course, the lives of people who were important, and who can be found in history here and there. I once participated – as I have mentioned before – in a café in an Austrian city. The following people were present: Seneca, no – Marcus Aurelius, the Duke of Reichstadt, the Marquise Pompadour, Marie Antoinette, Emperor Joseph and Frederick the Great. And all these people really believed in their flashback to past lives on Earth! In the real flashback there is something unpleasant for ordinary desires. This flashback really satisfies nothing but knowledge. And one must have a pure striving for knowledge if one wants to achieve anything at all in this field. If one does not have this pure striving for knowledge, then one can achieve nothing. One can achieve nothing in relation to outer nature if one cannot develop that selflessness in the good and bad sense of which I have spoken. But this must be increased if one now wants to develop, for instance, the ability to look back into earlier earth lives. And when this ability to look back arises in one's own experience, it is usually disappointing in the sense that it has now been interpreted. But it can never arise — and this is an empirical law — if one could somehow use what one learns from it in this earth life. I say: arise in oneself. So every time a review of earlier earth-lives really occurs within oneself, it can only satisfy one's knowledge. It can never help one in any way to satisfy any wishes in the earth-life in which one is living. If anyone believes that he must know his past lives in order to appreciate his position in the world, he will go very far astray if he tries to learn about these past lives by his own research. And in many other respects, too, the wishes that anyone may have are very seldom satisfied in any way by real, genuine spiritual research. With regard to these desires, the following must be noted, for example: First of all, it is the case that anyone who enters into spiritual research more as a layman or as an amateur – but of course anyone can do that, you can read about it in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” — who enters into it as a layman, he aspires above all to see a great deal, to see a great deal in the spiritual world. That is natural and understandable. And so he might believe that the experienced spiritual researcher is advising him to occupy himself with it a great deal and to devote all the time he has to spiritual research. A spiritual researcher who is aware of his responsibility and knowledgeable will not do that at all. He will not do it himself either, but he knows that it is very bad to withdraw one's ordinary thinking, the thinking one must apply in the outer world, from the outer world after becoming a spiritual researcher; that it is bad to withdraw one's thinking, which is directed towards the outer world, and no longer want to know anything about the outer world. If you become a mental ascetic for my sake and use all your thinking only to delve into the spiritual world, you will achieve nothing in reality. You will become a dreamy brooder. You will experience something within yourself that could border on, I would say, some kind of religious madness. But if you really want to become a spiritual researcher, it is necessary to take every precaution into account – and you will find them all listed in my book 'How to Know Higher Worlds' – in order to remain a reasonable person, the same reasonable person, as I said today eight days ago, who one was before one entered into spiritual research – at least no less reasonable. And to achieve this, the spiritual researcher tries to keep his interest aroused for everything that can arouse his interest in the outside world. Indeed, when one is in the process of developing as a spiritual researcher and is doing so as a rational human being, one will feel an ever-increasing need to broaden, not narrow, one's horizons in terms of observing and living with the world, to occupy oneself with as much as possible that is connected with experiences, observations and happenings in the external physical world. Because the more you are distracted from what you are trying to achieve, the better. In this way one achieves that thinking is again and again, I would like to say, disciplined by the outer, physical world and does not go on the free flight path, on which the soul can easily go, when it now withdraws from the outer world and buries itself as much as possible only into that, in which it believes to live as in a spiritual extended one. So, interest is what belongs to spiritual research like an external practical support. Therefore, the beginner in spiritual research in particular will have to be advised not to change his usual way of life significantly, but to enter into spiritual research without attracting attention to this external way of life, so to speak. If one changes one's external way of life too much, then the contrast between one's inner experience and one's experience with the outer world is not great enough – and it must be great. All the things that people strive for today, who seek their salvation in, well, how should I put it, withdrawing from the world, founding colonies, wearing long hair when they have worn it short before, or wearing it short when they have worn it long before, or putting on special clothes and so on, and also acquiring different habits, all this is evil. This is bad because one is demanding two things of oneself: to adapt to a new way of life and at the same time to adapt to the spiritual world. But what I said here eight days ago must be emphasized: While in any pathological state that develops in consciousness, this pathological state is there and the rational human being is gone, when developing self-awareness for spiritual research, the old human being must remain entirely as he is, and alongside that, the other consciousness must stand. The two must always be there side by side. One can say, in trivial terms: In the case of the spiritual researcher, the developed consciousness, the experience in another world, stands completely separate from what he otherwise is in the world. Nothing has changed in what one is in the world, other than what was previously. And one looks at what one was in the world, as one looks at one's experiences of yesterday. And just as one can no longer touch these yesterday's experiences, one does not touch what one was before entering the spiritual world. If you are a crazy person or a hypnotized person or a person who can somehow be considered pathological, then that is what you are and you cannot also be a reasonable person. Because you will never discover that someone is reasonable and a fool at the same time. That is precisely what matters, that one can say: the pathological consciousness is an altered consciousness; the consciousness has undergone a metamorphosis. If one is truly at home in the spiritual world, there has been no metamorphosis at all, but the new consciousness has taken its place alongside the old one. And that is the essential thing, what matters, so that man can really fully grasp the two consciousnesses. A further, I might say, uncomfortable aspect of attaining such spiritual goals as those indicated arises from the fact that the natural scientist naturally becomes accustomed to remaining in his field and world with what results from his field; that he therefore rejects - if he did it only for himself, it would not matter - as a world view that which lives just beyond his world view. All greatness of ordinary life, even of practical life, all greatness of natural science, too, is based on the way of thinking that has developed over the last three to four centuries. And usually, spiritual science does not regard what science achieves for life, even for external life, with less respect, but often with more; it is fully recognized by spiritual science. But precisely this spiritual science also knows that scientific thinking is easy — forgive me for using a trivial expression again — if you reject what you need as a thought. Indeed, today it is already the case that inventing an experiment involves much more than observing what comes to light through the experiment. Reading the mind of nature is easy and convenient. For this, little inner activity is needed. This activity cannot be compared at all with that which is needed if one wants to develop within oneself what has been discussed today. And so it happens that those who, in their consciousness, stand on the strict ground of science, but who, in their instincts, abandon themselves to the comfort of read thoughts, say quite naturally: Well, yes, that is something so contrived and fanciful that comes from this spiritual science. But there is something that one must perhaps admit without arrogance and pride: a more astute thinking is needed to recognize spiritual-scientific truths. But they do present themselves to astute thinking, for example, even if the person to whom they are to present themselves has not become a spiritual scientist. Today, people do not want to believe in authority; but, hand on heart - I have said this often enough: How many people believe, despite never having seen the corresponding experiment, that water can be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen, or other things! If you get to the bottom of things, there has never been a time as steeped in a belief in authority as the present day, and never a time as subject to dogmas as the present day. Only today one can say, as I stated decades ago in my introduction to Goethe's scientific writings, that people believe the dogma of experience, whereas in the past people accepted the dogma of authority. Just as one can apply in practical life, without having been in the laboratory oneself, what comes from the laboratory, so one can apply to one's world view, through corresponding really strenuous thinking, what the spiritual researcher brings to light and of which he knows that he has really discovered it in the spiritual world. These are the inconveniences in relation to spiritual research; but many such inconveniences could be enumerated. The main thing is this, that people very easily shrink from what must arise as a kind of soul mood when the path into the spiritual world is taken. First of all – and I would like to develop what I have to say historically, so to speak – it is a matter of historical development. Most people say, for example: Oh, there have been so many philosophers and philosophies in the world, and they have all claimed different things. Oh, it is best not to deal with these philosophers and philosophies at all! But such a judgment arises only under the influence of the belief that one can grasp a philosopher only if one understands him as a dogmatist and not, I might say, as an inner artist of thoughts. You can understand him as an inner artist of thought, and then you will get a great deal out of him, especially if you study him very closely, let him have a very intimate effect on you and believe nothing of it, then go to the other and see again a serious endeavor that lives in the pursuit of truth, and you will become versatile. And precisely through this one acquires a sense for being at home in the spiritual world. Indeed, one then experiences that one becomes clear about this, especially when one genuinely follows the paths in the presence of nature research: everything one gets from observation and experiment is basically inner experience, and the outer should never be called a natural law or something like that, but — Goethe has already chosen the magnificent expression — archetypal phenomenon, archetypal appearance. And when more is experienced in the external sense world, it is experienced through the activity of the inner. Thought must reach under the phenomenon. You cannot get down under the phenomenon without thinking. This requires an inner strengthening of thought, a real inner powerful experience and continuation of the line of thought. Under the influence of the scientific way of thinking, one does not want this. Therefore, from this point of view, the scientific way of thinking today still has something of the last remnant of ancient magic, as paradoxical as that may sound. Here it becomes clear to us that what we today call scientific experimentation and observation has developed in a straight line from ancient magic, where it was believed that through events — in the course of events through the ceremonial that was used as a basis — one could learn something that one did not experience inwardly. They shuddered at the thought of inner experience. They did not want to delve into things and wanted to be dictated to by the spirits outside, who magically live in the phenomena, that which one can only find by allowing one's inner experience to flow into the outer. But all such things are just as if someone were to say: The hands of the clock move forward because a little demon sits inside it, a little elemental spirit. Today, this is only noticed in a subtle way, but in the scientific experiment, or when the physiologists come and cut up small frog corpses to see the internal parts, you still have in mind that shudder at the secrets of nature that was present in ancient magic. This must also come out! One must not faint when one is called upon to extend one's thinking to include nature. One must have the strength to truly grasp natural phenomena. Among modern achievements — and all achievements, of course, are such — this particular weakness shows us what is commonly known as wanting to explore the spirit through external events, in that people get ready to sit around a table, for example, to seek the spirit through all kinds of mechanical, again external events, not by immersing one's own spirit in the essences of the world, but by external events. Of course, they only seek, well, let's say, in knocking tones or something else, the spirit. They don't think that they could find it much closer if they thought about the fact that when eight people are sitting around the table, there are eight embodied spirits that can be perceived differently than just the spirit that is knocking on the table through all sorts of nonsense. And so, like the other side, like a grotesque side, the counter-image of experimentation has become the order of the day, where one really wants to seek the spirit in the most crude way through things that one has to overcome. But then there is another side to this, which today is often called a worldview in the popular sense. It is quite natural that little by little, I would say, a shyness has developed to really develop this inner soul activity, because it is considered to be something really subjective. One believes that one is merely working out a subjective thing. One only becomes aware that one can find the objective under the subjective when one really penetrates into the matter. One shies away from really developing the inner being. It would be just as if one shrank from developing arms and legs before birth, because one would believe that one would thereby bring something subjective into the world and that arms and legs could never perceive anything objective. One shrinks back, one does not want to develop the inner being. One wants to develop only that which, as we have said, is rightly linked to the mere thinking apparatus. That is to say, one only wants to let the thinking apparatus work in oneself; one really withdraws into the inactive life of imagination. And the consequence of this is that all kinds of world views develop, about which one could certainly agree with the modern psychiatrist if one only takes an entirely objective, unbiased point of view. One can certainly agree with the modern psychiatrist, for example, about what is called monism today. It is clear to both of us that those people who are monists in today's crude materialistic sense do not have the courage to develop their inner activity, that they only allow their thinking apparatus to function and that they can naturally only receive a reflection of the external physical world from their thinking apparatus. If you open a psychiatric book at random, you will find the definition of this state of mind: A set of ideas arises which the person concerned considers to be correct because he is not aware that they only come from the thinking apparatus; he considers these ideas to be correct in the absolute sense. In the psychiatric sense, this is called delusional ideas as opposed to obsessive ideas. Many delusional ideas today are worldviews! If you look at the spiritual-scientific world view, you will see that it cannot fall into either of these errors, neither into the superstition of the external view of nature, which is still based on something of magic, that is, superstition , nor can it play into the realm of delusions, because the spiritual researcher is very clear about the fact that he himself creates and brings forth what he inwardly generates for the purpose of exploring the world, and he also knows: He is allowed to create and bring forth it himself. Then it can touch the outer world. Thus he can never fall into a world view that would be nothing but a delusion. But, as has often been suggested, the things that have been discussed again today arise when the scientific way of thinking, as it has developed over the past three to four centuries, is continued. But it must be continued in such a way that truth is not merely observed, but experienced. Therefore, a certain artistic feeling that goes into the most spiritual life is a much better preparation for spiritual-scientific experience than any other preparation. And therefore one will always find that the ascetic withdrawal from art, as it is so often noticeable in people who have aspirations of spiritual exploration of things, is of great evil, that in fact the spiritual research also broadens the horizon of the human being through the study of this artistic field. Hegel, for example, could not find a metaphysical meaning in art. For him, art was only the highest flowering of that which develops here in the physical world. But for the one who truly penetrates into the spiritual world, it is clear: that which must remain imagination here, as long as it moves on the physical plane as a human soul power, that is nevertheless born out of the spiritual, that is the physical image for the spiritual, that is the messenger that comes from the spiritual world. And if we can only grasp this supersensible mission of art, then we already have, I would say, a beginning for a truly living, atmospherically living penetration of the spiritual world. Otherwise, however, this spiritual science will continue to be treated as every spiritual impulse has been treated that has had to fit into the spiritual development of humanity. I have often pointed out here that by far the greatest number of people were hostile to the Copernican world view, understandably so, because it contradicted all habits of thought. Until then, people had thought: the earth stands still, one stands firmly on the stationary earth, the sun moves, the stars move. Now, all at once, one was supposed to rethink everything. And it cannot even be said that this Copernicanism became great precisely because, as monism demands today, it only looked at the external senses; for the external senses are precisely in line with what was thought earlier. The external sense world shows us, for this sense world itself, that the earth stands still and the sun moves. Copernicanism arrived at something new precisely by contradicting the sensory perception. And today one must arrive at something new by contradicting the usual conception of the soul as a matter of course, by contradicting precisely that which one would so easily believe is something in itself, namely what can be described as the eternal power of the human soul, namely thinking, feeling and willing, that one describes precisely that which now proves to be an inner semblance, an inner reflection of the truly eternal, and that the truly eternal, the truly eternal powers of the human soul, lie beneath this semblance. And only when one deepens one's imagination and thinking to such an extent that one goes beyond ordinary thinking to active thinking, where thinking becomes will – but will that is experienced, not merely observed as in the case of Schopenhauer – and where volition becomes thinking in that one can interpret it calmly, only then does one discover the eternal powers of the human soul, and one becomes aware that one is this physical human being, I would say, entirely according to a natural law, only conceived in a higher sense. One is this physical human being because one is transformed out of spiritual forces. In natural science, everyone knows: when you stroke the table in this way, warmth arises. There he believes in the transformation of forces. Today this is called the transformation of energies. Transformation of energies, transformation of forces, also exists in the spiritual world. What we are otherwise spiritually, transforms into the physical. This transformation of the spiritual is just as when heat is generated by friction. All that is needed is a change in thinking habits. This is difficult for some people. Not only do they have thinking habits that they cannot let go of, but these thinking habits have even hardened into concepts. And when someone speaks today of the continuation of natural science, of the living continuation as it is meant here, then those who are so very much inside, stick-thick inside the habits of thinking, will look and say: He wants to found a new religion, that is quite clear, he wants to found a new religion! All this must be understood, must be taken for granted. And it will be understood if one allows the soul's gaze to wander a little over the course of the development of the human mind. But from a certain point of view, spiritual science does give a certain satisfaction for what the best of people have striven for. Not an easy satisfaction. Even people are afraid of this slight satisfaction, which is also something that is opposed to spiritual science. There is someone who once objected: Yes, this spiritual science wants to answer the questions, the secrets of the world. Oh, how dull life will be when all questions have been answered, because the fact that one can have questions is what life is all about. Such people, who think this way, would be surprised at what happens to them when they enter into real spiritual science! Indeed, the lazy person believes that spiritual science is something like a spiritual morphine to calm him down. That is not what it is at all. The questions do not become fewer, the riddles do not become fewer, but rather they increase. New riddles and mysteries are constantly arising. And if, as an ordinary materialist, you pick up Haeckel's “Welträtsel” (World Riddles) or his better works, then you will have answers! For the spiritual researcher, only the questions arise; only the questions leap out. And he knows that the questions that arise for him are not answered by theories, but by experience. He is looking at a development of infinite perspective. And by raising questions, he is precisely reviving the life of the soul, preparing it for the answers that are given by ever new and new events. Life becomes richer and infinitely richer as more and more questions are raised. Again, this is an inconvenience for many who seek comfort and not knowledge. But on the whole, spiritual science is something that even the best people have sought, and what young Goethe already had in mind when he repeated to a wise man, whom he kept so hidden,:

Yes, one must only find it, this dawn! He who seeks it from the bottom because he is afraid of the sun will not find this dawn in the right sense. And this is the one who, as a spiritual researcher, would be afraid of the whole, full, living human existence. He who now wants to withdraw into some aesthetic cloud-cuckoo-land in order to find the spiritual world is like a person who seeks the dawn because he is afraid of the sun, of the full shining sun. But one can also seek the dawn in another sense, in the sense that it is the afterglow of the sun, which always shines and which also shone before it rose for us for our day, for other areas. If one seeks the spiritual dawn in this way, then the opened spiritual knowledge becomes becomes a means, a tool for the realm from which one came before the transformation into the physical human existence and to which one returns after the transformation of the physical human existence, to that spiritual power with which one truly scientifically reveals to oneself the law of repeated earth lives. Spiritual science then becomes the dawn that one experiences as a reflection of the sun's activity, which one cannot have directly by observing the sun's radiance that is assigned to one in the realm in which one will one day stand here in the physical world, to that sun's radiance that spreads out in the spiritual world, into which one enters by that one has precisely the courage and strength to step out of the sensual-physical world in order to enter another, and in this other world, which one can experience, in the sense that Hegel now in turn correctly sensed when he said: Oh, how miserable is the thought that seeks immortality only beyond the grave. If you seek the immortal, if you seek the eternal powers of the human soul, you can find them. But they must be sought. Because man is such a dual creature, he can truly find the other side of his nature. And for those who, from the standpoint of ordinary monism, disapprove of the search for the eternal powers of the human soul because it tears the soul apart into two parts, for them it must always be true that one says: Yes, one is no longer a monist when one admits that monon water breaks down and must break down into hydrogen and oxygen for knowledge, if one wants to learn to recognize it? One is truly no less a monist if one admits that true knowledge of the actual spiritual essence must be sought from that out of which the monon, the unity, the wholeness of man, becomes. But those who take such paths, as they have been tried to be characterized today, are certain that they lose nothing of what the world is to them and what they can be to themselves in the world by entering the spiritual world; that it is not a impoverishment of life that occurs, but an enrichment of life, and from this point of view, a higher satisfaction of life. Something new throbs through mind and soul, through thinking and heart, when that which can be aroused by the absence of fear of powerlessness, by the absence of shyness of courage, now permeates mind and soul, thinking and heart, in order to inwardly rise above oneself. And that is basically what the best have striven for. But just as everything in the development of the spirit could only come into being at a certain point in time, so too could spiritual science only come into being at a certain point in time. But however it is viewed, however it is regarded, however it is ridiculed and mocked, it will live on just as truly as other things have survived that were ridiculed and mocked. When someone first said, “All life comes from life,” he was expressing something for which, in those days, he was condemned to suffer the same fate as Giordano Bruno. Today it is taken for granted. Thus in the world, truths are transformed into human conceptions, from craziness to self-evidence. For many, spiritual science is a craziness today. In the future, it will also fall prey to this fate of becoming a matter of course. |

| 70a. The Human Soul, Fate and Death: The Rejuvenating Power of the German National Soul

18 Feb 1915, Hanover Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| And if we now look over to the East, to the Russian people. In Russia, much attention has been paid to Kant, to Hegel, Belinsky. But all this shows a very particular peculiarity: the thoughts of Central Europe become strangely ghostly in the East. |

| One of the keys to understanding the period is the fact that, while in England and France the poetic, philosophical, and scientific movements flowed mostly in separate channels, in Germany they touched or merged completely. Wordsworth sang and Bentham calculated; but Hegel caught the genius of poetry in the net of his logic; and the thought that discovers and explains, and the imagination that creates, worked together in fruitful harmony in the genius of Goethe. |

| 70a. The Human Soul, Fate and Death: The Rejuvenating Power of the German National Soul

18 Feb 1915, Hanover Rudolf Steiner |

|---|