| 272. Faust, the Aspiring Human: A Spiritual-Scientific Explanation of Goethe's “Faust”: “Faust”, the Greatest Work of Striving in the World, the Classical Phantasmagoria

30 May 1915, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In this way, I tried to throw a thought into the hustle and bustle of philosophy, and it will be interesting to see whether it will be understood or whether such a very plausible thought will be met again and again with the foolish objection: “Yes, but Kant has already proved that knowledge cannot approach things.” He proved it only from the point of view of knowledge, which can be compared to the consumption of grains of wheat, and not from the point of view of knowledge that arises with the progressive development that is in things. |

| 272. Faust, the Aspiring Human: A Spiritual-Scientific Explanation of Goethe's “Faust”: “Faust”, the Greatest Work of Striving in the World, the Classical Phantasmagoria

30 May 1915, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

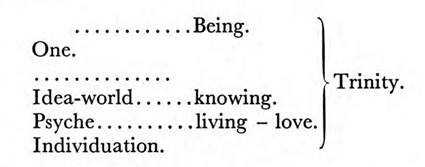

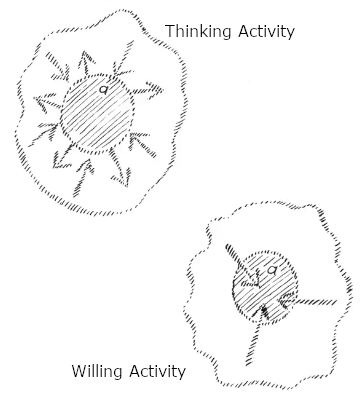

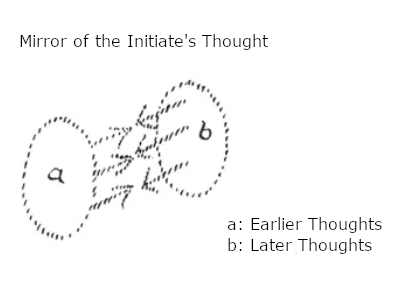

If you combine the reflections I presented here yesterday with the other lectures I gave here a week ago, you will, to a certain extent, gain an important key to much of spiritual science. I will only mention the main thoughts that we need for our further considerations, so that we can orient ourselves. About a week ago I pointed out the significance of the processes that, from the point of view of the physical world, are called processes of destruction. I pointed out that, from the point of view of the physical world, one actually only sees the real in what arises, what, as it were, emerges from nothingness and comes into noticeable existence. Thus, one speaks of the real when the plant struggles up from the root, developing leaf by leaf until it blossoms, and so forth. But one does not speak of the real in the same way when one looks at the processes of destruction, at the gradual withering, the gradual fading, the ultimate flowing away, one might say, to nothingness. But for anyone who wants to understand the world, it is eminently necessary that he also looks at the so-called destruction, at the processes of dissolution, at that which ultimately results for the physical world like flowing into nothingness. For consciousness can never develop in the physical world where mere sprouting and sprouting processes are taking place, but consciousness begins only where that which has sprouted in the physical world is in turn worn away and destroyed. I have pointed out how those processes that life evokes in us must be destroyed by the soul-spiritual if consciousness is to arise in the physical world. It is indeed the case that when we perceive anything external, our soul-spiritual must instigate processes of destruction in our nervous system, and these processes of destruction then mediate consciousness. Every time we become aware of something, the processes of consciousness must arise out of processes of destruction. And I have indicated how the most significant process of destruction, the process of death, is precisely the creator of consciousness for the time we spend after death. Through the fact that our soul and spirit experiences the complete dissolution and detachment of the physical and etheric bodies, the absorption of the physical and etheric bodies into the general physical and etheric world, our soul and spirit draws the strength – from the process of death our soul and spirit draws the strength to be able to have processes of perception between death and a new birth. The saying of Jakob Böhme: 'Thus, then, death is the root of all life' acquires through this a higher significance for the whole context of world phenomena. Now you will often have asked yourselves: What actually is the time that passes for the human soul between death and a new birth? It has often been pointed out that for the normal human life this time is a long one in relation to the time we spend here in the physical body between birth and death. It is short only for those people who use their lives in a way that is contrary to the world, who, I will say, come to do only that which in a real and true sense can be called criminal. Then there is a short lapse of time between death and a new birth. But for people who have not fallen prey to selfishness alone, but live their lives in a normal way between birth and death, there is usually a relatively long period of time between death and a new birth. But the question must, I would say, burn in our souls: What determines whether a human soul returns to a new physical embodiment at all? The answer to this question is intimately connected with everything that can be known about the significance of the destructive processes I have mentioned. Just think that when we enter physical existence with our souls, we are born into very specific circumstances. We are born into a certain age, driven to certain people. So we are born into very specific circumstances. You must realize very thoroughly that the content of our life between birth and death is actually filled with everything we are born into. What we think, what we feel, what we sense, in short, the whole content of our life depends on the time into which we are born. But now you will also easily be able to understand that what surrounds us when we are born into physical existence depends on the preceding causes, on what has happened before. Suppose, if I am to draw this schematically, we are born at a certain point in time and walk through life between birth and death. (It was drawn.) If you add what surrounds you, you do not stand there in isolation, but are the effect of what has gone before. What I mean is: you are brought together with what has gone before, with people. These people are children of other people, who in turn are children of other people, and so on. If we consider only these physical relationships of succession in generations, you will say: When I enter into physical existence I take something on from the people around me; during my education I take on much from the people around me. But these people, in turn, have also taken on very much from their ancestors, from the acquaintances and relatives of their ancestors, and so on. You could say that people have to search ever higher up to find the causes of what they themselves are. If you then let your thoughts go further, you can say that you can follow a certain current upwards through your birth. This current has, as it were, brought with it everything that surrounds us in the life between birth and death. And if we continue to follow this current upwards, we would then come to a point in time where our previous incarnation lay. So by following the time upwards, before our birth, we would have a long time in which we dwelled in the spiritual world. During this time, many things have happened on earth. But what has happened has brought with it the conditions in which we live, into which we are born. And then, in the spiritual world, we finally come to the time when we were on earth in a previous incarnation. When we talk about these circumstances, we are definitely talking about average circumstances. Of course, there are many exceptions, but they all lie, I would say, in the line I indicated earlier for natures that come to earthly embodiment more quickly. What determines whether we are born here again after a period of time has passed? Well, if we look at our previous embodiments, we were also surrounded by circumstances during our time on earth, and these circumstances had their effects. We were surrounded by people, these people had children, and passed on to the children their feelings and ideas. But if you follow the course of historical life, you will say to yourself: there will come a time in the course of evolution when you will no longer be able to recognize anything truly the same or even similar in the descendants as in the ancestors. All this is transferred, but the basic character that is present at a particular time appears in the children in a weakened form, in the grandchildren even more weakened and so on, until a time approaches when there is nothing left of the basic character of the environment in which one was in the previous incarnation. So that the stream of time works to destroy what the basic character of the environment once was. We watch this destruction in the time between death and a new birth. And when the character of the earlier age has been erased, when there is nothing left of it, when what it was like in an earlier incarnation has been destroyed, then the time comes when we enter earthly existence again. Just as the second half of our life is actually a kind of wearing down of our physical existence, so between death and a new birth there must be a kind of wearing down of earthly conditions, a destruction, a annihilation. And new conditions, new surroundings, into which we are born, must be there. So we are reborn when all that for the sake of which we were born before has been destroyed. So this idea of destruction is connected with the successive return of our incarnation on earth. And what our consciousness creates at the moment of death, when we see the body fall away from our spiritual and mental self, is strengthened at this moment of death, at this contemplation of destruction for the contemplation of the process of destruction that must take place in the circumstances on earth between our death and a new birth. Now you will also understand that someone who has no interest at all in what surrounds him on earth, who basically is not interested in any person or any being, but is only interested in what is good for himself, and simply steals from one day to the next, that he is not very strongly connected to the conditions and things on earth. He is also not interested in following their slow erosion, but comes very soon to repair them, to really live with the conditions with which he must live, so that he learns to understand their gradual destruction. He who has never lived with earthly conditions does not understand their destruction, their dissolution. Therefore, those who have lived very intensely in the basic character of any age, have absorbed themselves in the basic character of any age, will, above all, tend, if nothing else intervenes, to bring about the destruction of that into which they were born, and to reappear when a completely new one has emerged. Of course, I would say that there are exceptions at the top. And these exceptions are particularly important for us to consider. Let us assume that one lives one's way into such a movement, as the spiritual-scientific movement is now, at this point in time, where it does not agree with everything that is in the surrounding world, where it is something completely alien to the surrounding world. In this sense, the spiritual-scientific movement is not something we are born into, but something we have to work on, something we want to enter into the spiritual cultural development of the earth. In this case it is a matter of living with conditions that are contrary to spiritual science and then reappearing on earth when the earth has changed so much that the spiritual-scientific conditions can truly take hold of cultural life. So here we have the exception to the upside. There are exceptions downwards and upwards. Certainly, the most earnest co-workers of spiritual science today are preparing to reappear in an earthly existence as soon as possible, by working at the same time during this earthly existence to eliminate the conditions into which they were born. So you see, when you take the last thought, that you are helping, so to speak, the spiritual beings to direct the world by devoting yourself to what lies in the intentions of the spiritual beings. If we consider the conditions of the times today, we have to say: on the one hand, we have something that is heading towards decadence and decline. Those who have a heart and soul for spiritual science have been placed in this age, so to speak, to see how it is ripe for decline. Here on earth they are introduced to that with which one can only become acquainted on earth, but they carry this up into the spiritual worlds, now see the decline of the age and will return when that is to bring about a new age, which lies precisely in the innermost impulses of spiritual striving. Thus the plans of the spiritual guides, the spiritual leaders of earthly evolution, are effectively furthered by what such people, who occupy themselves with something that is, so to speak, not the culture of the time, absorb into themselves. You are perhaps familiar with the accusations that are very often made by people of today to those who profess spiritual science, namely that they deal with something that often appears to be outwardly unfruitful, that does not outwardly intervene in the conditions of the time. Yes, there is really a necessity for people in earthly existence to occupy themselves with that which is of significance for further development, but not immediately for the time. If anyone objects to this, then he should just consider the following. Imagine that these were consecutive years:  We could then go further. Suppose these were consecutive years and that these were the grain crops w w of the consecutive years. And what I am drawing here would always be the mouths > that consume these grains of grain. Now someone may come and say: Only the arrow that goes from the grains of grain to the mouths > is important, because that sustains the people of the following years. And he can say: Whoever thinks realistically only looks at these arrows going from the grain to the mouth. But the grain cares little about this arrow. It does not care at all, but has only the tendency to develop each grain of wheat into the next year. The grain kernels only care about this arrow; they don't care at all about being eaten. That is a side effect, something that arises along the way. Each grain kernel has, if I may say so, the will, the impulse to go over into the next year to become a grain kernel again. And it is good for the mouths that the grains follow this arrow direction, because if all the grains followed this arrow direction, then the mouths here would have nothing more to eat next year! If the grains from the year 1913 had all followed this arrow, then the mouths from the year 1914 would have nothing more to eat. If someone wanted to carry out materialistic thinking consistently, he would examine the grains of corn to see how they are chemically composed so that they produce the best possible food products. But that would not be a good observation; because this tendency does not lie in the grains of corn at all, but in the grains of corn lies the tendency to ensure further development and to develop over into next year's grain of corn. But it is the same with the end of the world. Those truly follow the course of the world who ensure that evolution continues, and those who become materialists follow the mouths that only look at this arrow here. But those who ensure that the course of the world continues need not be deterred in their striving to prepare the next following times, any more than the grains of corn are deterred from preparing those of the following year, even if the mouths here long for the completely different arrows. I pointed this out at the end of Riddles of Philosophy, pointing out that what we call materialistic knowledge can be compared to eating grain seeds, that what happens in world events really happens in the world, can be compared to reproduction, to what happens from one grain seed to the next year's. Therefore, what is called scientific knowledge is just as insignificant for the inner nature of things as eating is without inner significance for the growth of grain fruits. And today's science, which is only concerned with the way in which what can be known about things is received by the human mind, is doing exactly the same as the man who uses the grain for food, because what the grains of corn are when we eat them has nothing to do with the inner nature of the grains of corn, just as the outer knowledge has nothing to do with what develops inside the things. In this way, I tried to throw a thought into the hustle and bustle of philosophy, and it will be interesting to see whether it will be understood or whether such a very plausible thought will be met again and again with the foolish objection: “Yes, but Kant has already proved that knowledge cannot approach things.” He proved it only from the point of view of knowledge, which can be compared to the consumption of grains of wheat, and not from the point of view of knowledge that arises with the progressive development that is in things. But we must familiarize ourselves with the fact that we have to repeat again and again to our age and to the age to come, in all possible forms, only not in hasty forms and not in agitative forms, not in fanatical forms, what the principle and essence of spiritual science is, until it is drummed into us. For it is precisely the characteristic of our age that Ahriman has made the skulls so hard and thick, and that they can only be softened slowly. So no one should shrink, I would say, from the necessity of emphasizing again and again, in all possible forms, what the essence and impulse of spiritual science is. But now let us turn to another conclusion that was drawn here yesterday in connection with a number of assumptions: the conclusion that reverence for the truth must grow in our time, reverence for knowledge, not for authoritative knowledge, but for the knowledge that one acquires. There must be a growing realization that one should not judge out of nothing, but out of one's acquired knowledge of the workings of the world. Now, by being born into a particular age, we are dependent on our environment, completely dependent on what is in our environment. But, as we have seen, this is connected with the whole stream of development, with the whole striving that leads upwards, so that we are born into circumstances that depend on the preceding circumstances. Just consider how we are placed into them. Of course we are placed in it by our karma, but we are still placed in that which surrounds us as something quite definite, as something that has a certain character. And now consider how we thereby become dependent in our judgment. This is not always clearly evident to us, but it is really so. So that we have to ask ourselves, even if it is related to our karma: What if we had not been born at a certain point in time and in a certain place, but fifty years earlier in a different place? How would it be then? Wouldn't we have received the form and inner direction of our judgments from the different circumstances of our environment, just as we have received them from where we were born? So that on closer self-examination we really come to the conclusion that we are born into a certain milieu, into a certain environment, that we are dependent on this milieu in our judgments and in our feelings, that this milieu reappears, as it were, when we judge. Just think how it would be different, I just want to say, if Luther had been born in the 19th century and in a completely different place! So even with a personality who has an enormous influence on their surroundings, we can see how they incorporate into their own judgments that which is characteristic of the age, whereby the personality actually reflects the impulses of the age. And this is the case for every person, except that those for whom it is most the case are the least aware of it. Those who most closely reflect the impulses of their environment, into which they were born, are usually the ones who speak the most about their freedom, their independent judgment, their lack of prejudice, and so on. On the other hand, when we see people who are not as thoroughly dependent as most people are on their environment, we see that it is precisely such people who are most aware of what makes them dependent on their environment. And one of those who never got rid of the idea of dependence on their environment is the great spirit, of whom we have now seen another piece pass before our eyes, is Goethe. He knew in the most eminent sense that he would not be as he was if he had not been born in 1749 in Frankfurt am Main and so on. He knew that, in a sense, his age speaks through him. This moved and warmed his behavior in an extraordinary way. He knew that by seeing certain times and circumstances in his father's house, he formed his judgment. By spending his student days in Leipzig, he formed his judgment. By coming to Strasbourg, he formed his judgment. That is why he wanted to get out of these circumstances and into completely different ones, so that in the 1880s, one might say, he suddenly disappeared into the night and fog and only told his friends about his disappearance when he was already far away, after he could not be brought back under the circumstances at the time. He wanted to break out so that something else could speak through him. And if you take many of Goethe's utterances from his developmental period, you will notice this feeling, this sense of dependence on the environment everywhere. Yes, but what would Goethe have had to strive for if, at the moment when he had truly come to realize that one is actually completely dependent on one's environment, if he had connected his feelings, his perceptions of this dependence with the thoughts we have expressed today? He would have had to say: Yes, my environment is dependent on the whole stream of evolution right back to my ancestors. I will always remain dependent. I would have to transport myself back in thought, in soul experience, to a time when today's conditions did not yet exist, when completely different conditions prevailed. Then, if I could transport myself into these conditions, I would come to an independent judgment, not just judging as my time judges about my time, but judging as I judge when I completely transcend my time. Of course, it is not necessary for such a person, who perceives this as a necessity, to place himself in his own previous incarnation. But essentially he must place himself at a point in time that is connected with an earlier incarnation, where he lived in completely different circumstances. And when he now transfers himself back into this incarnation, he will not be dependent as before, because the circumstances have become quite different, the earlier circumstances have since been destroyed, perished. It is, of course, different if I now transfer myself back to a time when the whole environment, the whole milieu has disappeared. What do you actually have then? Yes, one must say: before, one lives in life, one enjoys life; one is interwoven with life. One can no longer be interwoven with the life that has perished, with the life of an earlier time; one can only relive this life spiritually and mentally. Then one would be able to say: “We have life in its colorful reflection.” Yes, but what would have to happen if such a person, feeling this, wanted to depict this emergence from the circumstances of the present and the coming to an objective judgment from a point of view that is not possible today? He would have to describe it in such a way that he would be transported back into completely different circumstances. Whether this is exactly the previous incarnation or not is not important, but rather the circumstances on earth were completely different. And he would have to strive to fill his soul with the impulses that were there at that time. He would have to, as it were, place himself in a kind of phantasmagoria, identify with this phantasmagoria and live in it, live in a kind of phantasmagoria that represents an earlier time. But that is what Goethe strives for by continuing his “Faust” in the second part. Consider that he has initially brought his Faust into the circumstances of the present. There he lets him experience everything that can be experienced in the present. But in spite of all this, he has a deep inner feeling: “This cannot lead to any kind of true judgment, because I am always inspired by what is around me; I have to go out, I have to go back to a time when the circumstances have been completely changed up to our time, and so they cannot affect the judgment.” Goethe therefore allows Faust to go all the way back to classical Greek times and to enter, to come together with the classical Walpurgis Night. That which he can experience in the deepest sense in the present has been depicted in the Nordic Walpurgis Night. Now he must go back to the classical Walpurgis Night, because from the Nordic Walpurgis Night to the classical Walpurgis Night, all conditions have changed. What was essential in the classical Walpurgis Night has disappeared, and new conditions have arisen, which are symbolized by the Nordic Walpurgis Night. There you have the justification for Faust's return to Greek times. The whole of the second part of “Faust” is the realization of what one can call: “In the colored reflection we have life.” First, there is still a passage through the conditions of the present, but those conditions that are already preparing destruction. We will see what is developing at the “imperial court,” where the devil takes the place of the fool and so on. We see through the creation of the homunculus how the emergence from the present is sought, and how in the third act of “Faust” the classical scene now occurs. Goethe had already written the beginning around the turn of the 18th century; the most important scenes were not added until 1825, but the Helena scene was already written (800) and Goethe calls it a “classical phantasmagoria” to suggest through the words that he means a return to conditions that are not the physical, real conditions of the present. That is the significant thing about Goethe's Faust poetry, that it is, I would say, a work of striving, a work of wrestling. I have really emphasized clearly enough in recent times that it would be nonsense to regard Goethe's Faust poetry as a completed work of art. I have done enough to show that it cannot be considered a finished work of art. But as a work of striving, as a work of wrestling, this Faust epic is so significant. Only then can one understand what Goethe intuitively achieved when one opens oneself to the light that can fall from our spiritual science on such a composition and sees how Faust looks into the classical period, into the milieu of Greek culture, where within the fourth post-Atlantic period very different conditions existed than in our fifth post-Atlantic period. One is truly filled with the greatest reverence for this struggle when one sees how Goethe began to work on this Faust in his early youth, how he abandoned himself to everything that was accessible to him at the time, without really understanding it very well. Truly, when approaching Faust, one must apply this point of view of spiritual science, for the judgments that the outer world sometimes brings are too foolish in relation to Faust. How could it escape the attention of the spiritual scientist when, time and again, people who think they are particularly clever approach and point out how magnificently the creed is expressed by this Faust, and say: Yes, compared to what so many people say about some confession of faith, one would have to remember more and more the conversation between Faust and Gretchen:

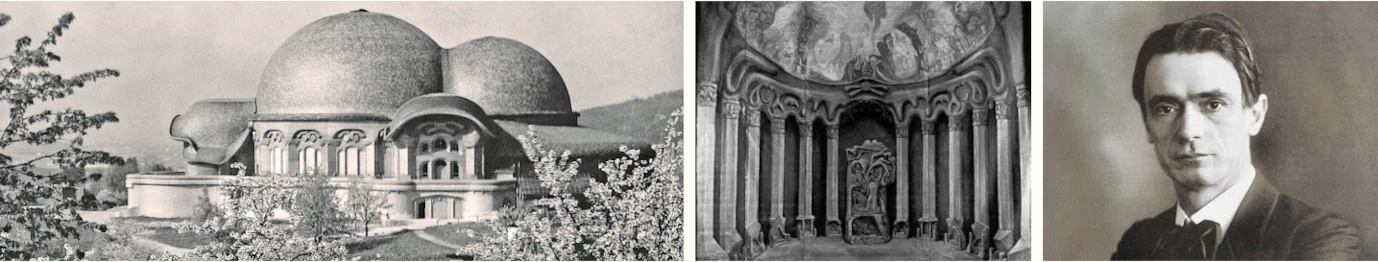

Well, you know what Faust is discussing with Gretchen, and what is always mentioned when someone thinks they have to emphasize what should not be seen as religious reflection and what should be seen as religious sentiment. But what is not considered is that in this case, Faust was formulating his religious creed for the sixteen-year-old Gretchen, and that all the clever professors are then demanding that people never progress beyond the Gretchen point of view in their religious understanding. The moment you present that confession of Faust to Gretchen as something particularly sublime, you demand that humanity never rise above the Gretchen point of view. That is actually easy and convenient to achieve. It is also very easy to boast that everything is feeling and so on, but you don't realize that it is the Gretchen point of view. Goethe, for his part, strove quite differently to make his Faust the bearer of an ongoing struggle, as I have now indicated again with reference to this placing himself in a completely earlier age in order to get at the truth. Perhaps at the same time or a little earlier when Goethe wrote this “classical-romantic phantasmagoria”, this placing of Faust in the world of the Greeks, he wanted to make clear to himself once again how his “Faust” should actually proceed, what he wanted to present in “Faust”. And so Goethe wrote down a scheme. At that time, there was a version of his “Faust” available: a foundation, a number of scenes from the first part and probably also the Helena scene. Goethe wrote down: “Ideal pursuit of influence and empathy in all of nature.” So, as the century drew to a close, Goethe took up, as he said, “the old thread, the barbaric composition”, at Schiller's suggestion. That is how he rightly described his “Faust” at the end of the century, because it was written scene by scene. Now he said to himself: What have I actually done there? And he stood before the soul of this striving Faust: out of erudition, closer to nature. He wrote down: “I wanted to set forth 1. Ideal striving for influence and empathy in all of nature. 2. Appearance of the spirit as a world and deed genius. This is how he sketches the appearance of the earth spirit. Now I have shown you how, according to the appearance of the earth spirit, it is actually the Wagner who appears, and who is only a means to the self-knowledge of Faust, which is in Faust himself, a part of Faust. What is arguing in Faust? What is Faust doing now that something is arguing in him? He realizes: Until now you have only lived in your environment, in what the outer world has offered you. He can see this most clearly in the part that is within him, in Wagner, who is quite content. Faust is in the process of attaining something in order to free himself from what he is born into, but Wagner wants to remain entirely as he is, to remain in what he is on the outside. What is it that lives out itself outwardly in the world from generation to generation, from epoch to epoch? It is the form into which human striving is molded. The spirits of form work outside in that which we are to live in. But man must always, if he does not want to die in the form, if he really wants to progress, strive beyond this form. “Struggle between form and formlessness,“ Goethe also writes. ”3. Struggle between form and formlessness." But now Faust looks at the form: the Faust in Wagner in there. He wants to be free of this form. This is a striving for the content of this form, a new content that can arise from within. We could also have looked at all possible forms and studied all possible styles and then built a new building, as many architects of the 19th century did, as we find it everywhere outside. We would not have created anything new from the form that has come about in the evolution of the world: Wagner nature. But we preferred to take the 'formless content'. We have sought to take the spiritual science that is vividly experienced from what is initially formless, what is only content, and to pour it into new forms. This is what Faust does by rejecting Wagner:

“4. Preference for formless content,” Goethe also writes. And that is the scene he has written, in which Faust rejects Wagner: “Preference for formless content over empty form.” But over time, the form becomes empty. If, after a hundred years, someone were to perform a play exactly as we are performing it today, it would again be an empty form. That is what we must take into account. That is why Goethe writes: “5. Content brings form with it.” That is what I want us to experience! That is what we want to achieve with our building: form brings content with it. And, as Goethe writes, “Form is never without content.” Of course it is never without content, but Wagnerian natures do not see the content in it, which is why they only accept the empty form. The form is as justified as it can possibly be. But the point is to make progress, to overcome the old form with the new content. “6. Form is never without content.”

And now a sentence that Goethe writes down to give his “Faust”, so to speak, the impulse, a highly characteristic sentence. For the Wagnerian natures, they think about it: Yes, form, content - how can I concoct that - how can I bring it together? — You can very well imagine a person in the present day who wants to be an artist and who says to himself: Well, spiritual science, all right. But it's none of my business what these tricky minds come up with as spiritual science. But they want to build a house that, I believe, contains Greek, Renaissance, Gothic styles; and there I see what they are thinking in the house they are building, how the content corresponds to the form. One could imagine that this will come. It must come, if people think about eradicating contradictions, while the world is precisely composed of contradictions, and it is important that you can put the contradictions next to each other. So Goethe writes: "7. These contradictions, instead of uniting them, are to be made more disparate. That is, he wants to present them in his “Faust” in such a way that they emerge as strongly as possible: “These contradictions, instead of uniting them, make them more disparate.” And to do that, he juxtaposes two figures again, where one lives entirely in form and is satisfied when he adheres to form, greedily digs for treasures of knowledge and is happy when he finds earthworms. In our time, we could say: greedily striving for the secret of becoming human and glad when he finds out, for example, that the human being has emerged from an animal species similar to our hedgehogs and rabbits. Edinger, one of the most important philosophers of the present day, recently gave a lecture on the emergence of the human being from a primal form similar to our hedgehog and rabbit. The theory that the human race descended from apes, prosimians, and so on, is no longer accepted by science; we have to go further back, to an earlier point of divergence between the animal species. Once upon a time there were ancestors that resembled the hedgehog and the rabbit, and on the other hand we have man as our ancestor. It is not true that because man is most similar to the rabbit and the hedgehog in certain things in terms of his brain formation, he must have descended from something similar. These animal species have survived, everything else has of course died out. So dig greedily for treasures and be glad if you find rabbits and hedgehogs. That is one striving, striving only in form. Goethe wanted to place it in Wagner, and he knows well that it is a clever striving; people are not stupid, they are clever. Goethe calls it: “Bright, cold, scientific striving.” “Wagner,” he adds. “8. Bright, cold, scientific striving: Wagner.” The other, the disparate, is what one wants to work out with all the fibers of the soul from within, after not finding it in the forms within. Goethe calls it “dull, warm, scientific striving”; he contrasts it with the other and adds “student” to it. Now that Wagner has been confronted with Faust, the student also confronts him. Faust remembers how he used to be a student, what he took in as philosophy, law, medicine and, unfortunately, theology. What he said to himself when he was still like the student: “All of this makes me feel as stupid as if a mill wheel were turning in my head.” But that's over. He can no longer put himself back in that position. But it all had an effect on him. So: “9. Dull, warm, scientific striving: schoolboy.” And so it continues. From this point onwards, we actually see Faust becoming a schoolboy and then once again delving into everything that allows one to grasp the present. Goethe now calls the rest of Part One, insofar as it was already finished and was still to be finished: “10. The enjoyment of life as seen from the outside; in dullness and passion, first part.” Goethe is clear about what he has created. Now he wants to say: how should Faust really come out of this enjoyment of life into an objective worldview? — He must come to the form, but he must now grasp the form with his whole being. And we have seen how far he must go back, to where completely different conditions exist. There the form then meets him as a reflection. There the form meets him in such a way that he now absorbs it by becoming one with the truth that was justified at that time, and discards everything that had to happen at that time. In other words, he tries to put himself in the position of the time insofar as it was not permeated by Lucifer. He tries to go back to the divine point of view of ancient Greece. And when you immerse yourself in the outside world in such a way that you enter it with your whole being, but take nothing from the circumstances into which you have grown, then you arrive at what Goethe describes as beauty in the highest sense. That is why he says: “Enjoyment of the deed”. Now no longer: enjoyment of the person, enjoyment of life. Enjoyment of the deed, going out, gradually moving away from oneself. Settling into the world is enjoyment of the deed outwards and enjoyment with consciousness. “ii. Enjoyment of the deed outwards and enjoyment with consciousness: beauty, second part.” What Goethe was no longer able to achieve in his struggle because his time was not yet the time of spiritual science, he sketches out for himself at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century. For Goethe has very significant words at the end of this sketch, which he wrote there, and which was a recapitulation of what he had done in the first part. He had already planned to write a kind of third part to his “Faust”; but it only became the two parts, which do not express everything Goethe wanted, because he would have needed spiritual science to do so. What Goethe wanted to depict here is the experience of the whole of creation outside, when one has emerged from one's personal life. This whole experience of Creation outside, in objectivity in the world outside, so that Creation is experienced from within, by carrying what is truly within outwards, that is sketched out by Goethe, I would say, stammering with the words: 'Enjoyment of Creation from within' - that is, not from his standpoint, by stepping out of himself. “12. Enjoyment of Creation from Within.” With this “Enjoyment of Creation from Within,” Faust had now entered not only the classical world, but the world of the spiritual. Then there is something else at the end, a very strange sentence that points to the scene that Goethe wanted to do, did not do, but did want to do, that he would have done if he had already lived in our time, but that shone before him. He wrote: "13. Epilogue in Chaos on the Way to Hell. I have heard very clever people discuss what this last sentence: “Epilogue in Chaos on the Way to Hell” means. People said: So, in 1800, Goethe really still had the idea that Faust goes to hell and delivers an epilogue in the chaos before entering hell? So it was only much, much later that he came up with the idea of not letting Faust go to hell! I have heard many, many very learned discussions about this, as well as many other discussions! It means that in 1800 Goethe was not yet free from the idea of letting Faust go to hell after all. But they did not think about the fact that it is not Faust who delivers the epilogue, but of course Mephistopheles, after Faust has escaped him in heaven! The epilogue would be, as we would say today, Lucifer and Ahriman on their way to hell; on their way to hell, they would discuss what they had experienced with the striving Faust. I wanted to draw your attention to this recapitulation and to this exposition by Goethe once again because it shows us in the most eminent sense how Goethe, with all that he was able to gain in his time, strove towards the path that leads straight up into the realm of spiritual science. We shall only be able to view Faust aright if we ask ourselves: Why has Faust, in its innermost core, remained an incomplete work of literature, despite being the greatest work of striving in the world, and why is Faust the representative of all humanity in that he strives out of his environment and is even carried into an earlier age? Why has this Faust nevertheless remained an unsatisfactory work of literature? Because it represents the striving for what spiritual science should incorporate into human cultural development. It is good to focus attention on this fact: that at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century, a work of literature was created in which the figure of Faust, who forms the center of this work, was to be lifted out of all the restrictive limitations that must surround human beings, by having him go through his life in repeated lives on earth. The significance of Faust lies in the fact that, however intensely he has outgrown his nationality, he has nevertheless outgrown nationality and grown into the universal human condition. Faust has nothing of the narrow limitations of nationality, but strives upward to the general humanity, so that we find him not only as the Faust of modern times, but in the second part as a Faust who stands as a Greek among Greeks. It is a tremendous setback in our time, when in the course of the 19th century people began to place the greatest emphasis on the limits of human development again, and even see in the “national idea” an idea that could somehow still be a cultural force for our era. Mankind could wonderfully rise to an understanding of what spiritual science should become, if one wanted to understand something like what is secretly contained in “Faust”. It was not for nothing that Goethe said to Eckermann, when he was writing the second part of his “Faust”, that he had secretly included in the “Faust” much that would only come out little by little. Hermann Grimm, whom I have often spoken to you about, has pointed out that it will take a millennium to fully understand Goethe. I have to say: I believe that too. When people have delved even deeper than they have in our time, they will understand more and more of what lies within Goethe. Above all, what he strove for, what he struggled for, what he was unable to express. Because if you were to ask Goethe whether what he put into the second part of 'Faust' was also expressed in his 'Faust', he would say: No! But we can be convinced that if we were to ask him today: Are we on the same path of spiritual science that you strove for at that time, as it was possible at that time? - he would say: That which is spiritual science moves in my paths. And so it will be, since Goethe allowed his Faust to go back to Greek times in order to show him as one who understands the present, it will be permissible to say: reverence for truth, reverence for knowledge that struggles out of the knowledge of the environment, out of the limitations of the surroundings, that is what we must acquire for ourselves. And it is truly a warning of the events of the times, which show us how humanity is heading in the opposite direction, towards judging things as superficially as possible, and would prefer to stop at the events of 1914 in order to explain all the terrible things we are experiencing today.But anyone who wants to understand the present must judge this present from a higher vantage point than this present itself is. That is what I have tried to put into your souls as a feeling in these days, a feeling that I have tried to show you follows from a truly inner, living understanding of spiritual science, and how it has been striven for by the greatest minds of the past, of whom Goethe is one. Only by not merely absorbing what arises in our soul in these contemplations as something theoretical, but by assimilating it in our souls and letting it live in our soul's meditations, does it become living spiritual science. May we hold it so with this, with much, indeed with all that passes through our soul as spiritual science. |

| 4. The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity (1986): The Idea of Spiritual Activity

Tr. William Lindemann Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| [ 44 ] When Kant says of duty: “Duty! You great and sublime name! You who include within yourself nothing beloved which bears an ingratiating character, but demand submission,” you who “set up a law ..., before which all inclinations grow silent, even though they secretly work against it,”5 then, out of the consciousness of the free spirit, the human being replies, “Freedom! |

| 4. The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity (1986): The Idea of Spiritual Activity

Tr. William Lindemann Rudolf Steiner |

|---|