| 220. Man and Cosmos

07 Jan 1923, Dornach Tr. Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The things mentioned above are facts evident to the ordinary human consciousness. But if you study the anthroposophical literature, you will find that there are other possibilities of consciousness differing from those which exist for the earthly human being in ordinary life. |

| There are, however, other possibilities of consciousness, which remain more unconscious in the earthly human being and are pushed into the depths of his soul life; yet they are just as important, and frequently far more important in human life than the facts of consciousness which exhaust themselves in what I have described so far. |

| For we really perceive something with each organ. The human being is in every way a great sense organ, and as such, he has differentiated, specified sense organs in the single organs of his body. |

| 220. Man and Cosmos

07 Jan 1923, Dornach Tr. Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Within this course of lectures I intend to speak of things which are connected with the preceding lectures, but which bring results of spiritual science drawn from a deeper source and show how the human being is placed in the universe. We speak of man in such a way that we envisage, to begin with, his physical organization and his etheric or vital body revealed to spiritual investigation; and then we speak of the astral body and of the Ego organization. But we do not yet grasp man's structure if we simply enumerate these things in sequence, for each of these members has a different place in the universe. We are able to grasp man's position in the cosmos only if we understand how these different members are placed in the universe. When we study the human being, as he stands before us, we find that these four members of human nature interpenetrate in a way which cannot at first be distinguished; they are united in an alternating activity, and in order to understand them we must first study them separately, as it were, and consider each one in its special relation to the universe. We can do this in the following way, by setting out, not from a more general aspect, but from a definite standpoint. Bear I mind, to begin with, the more peripheric aspect of man, the external boundary, what is outside him. From other anthroposophical studies we know that we discover certain senses only when we penetrate, as it were, below the surface of the human form, into man's inner life. But essentially speaking, also the senses which transmit us a knowledge of our own inner being, have to be sought in regard to their starting point, and to begin with in a very unconscious way, on the inner side of the surface of man's being. We may therefore say: Everything in man existing in the form of senses should be looked for on the surface. It suffices to bear in mind one of the more prominent senses; for example, the eye or the ear—these show that the human being must obtain certain impressions from outside. How matters really stand in regard to these senses should, of course, be studied more deeply, by a more profound research. This has already been done here for some of the human senses. But the way in which these things appear in ordinary life induces us to say: A sense organ—for example, the eye or the ear—perceives things through impressions coming from outside. Man's position on earth easily enables us to see that the chief direction which determines the influences enabling him to have sensory perceptions can approximately be described as “horizontal.” A more accurate study would also show us that this statement is absolutely correct; for when perceptions apparently come from another direction, this is an illusion. Every direction relating to perception must in the end follow the horizontal. And the horizontal is the line which runs parallel to the surface of the earth. If I now draw this schematically, I would therefore have to say: If this is the surface of the earth, with the perceiving human being upon it, the chief direction of his perceptions is the one which runs parallel to the earth. All our perceptions follow this direction. And when we study the human being, it will not be difficult to say that the perceptions come from outside; they reach, as it were, man's inner life from outside. What meets them from inside? From inside we bring towards them our thinking, the power of forming representations or thoughts. If you consider this process, you cannot help saying: When I perceive through the eye, I obtain an impression from outside, and my thinking power comes from inside. When I look at the table, its impression comes from outside. I can retain a picture of the table in my memory through the representing or thinking power which comes from within. We may therefore say: If we imagine a human being schematically, the direction of his perceptions goes from the outside to the inside, whereas the direction of his thinking goes from the inside to the outside. What we thus envisage, is connected with the perceptions of the earthly human being in ordinary life, of the earthly human being appearing to us externally in the present epoch of the earth's development. The things mentioned above are facts evident to the ordinary human consciousness. But if you study the anthroposophical literature, you will find that there are other possibilities of consciousness differing from those which exist for the earthly human being in ordinary life. I would now ask you to form, even approximately and vaguely, a picture of what the earthly human being perceives. You look upon the colours which exist on earth, you hear sounds, you experience sensations of heat, and so forth. You obtain contours of the things you perceive, so that you perceive their shape, and so forth. But all the things in our environment, with which we have thus united ourselves, only constitute facts pertaining to our ordinary consciousness. There are, however, other possibilities of consciousness, which remain more unconscious in the earthly human being and are pushed into the depths of his soul life; yet they are just as important, and frequently far more important in human life than the facts of consciousness which exhaust themselves in what I have described so far. For the human constitution which man has here on earth, the things below the surface of the earth are just as important as those which exist in the earth's circumference. The circumference of the earth, what exists around the earth, may be perceived by the ordinary senses and grasped by the representing capacity which meets sense perception. This fills the consciousness of the ordinary human being living on the earth. But let us consider the inside of the earth. Simple reflection will show you that the inside of the earth is not accessible to ordinary consciousness. We may, to be sure, make excavations reaching a certain depth and in these holes—for example in mines—observe things in the same way in which we observe them on the earth's surface. But this would be the same as observing a human corpse. When we study a corpse, we study something which no longer constitutes the whole human being, but only a residue of man as a whole. Indeed, those who are able to consider such things in the right way must even say: We are then looking upon something which is the very opposite of man. The reality of earthly man is the living human being walking around, and to him belong the bones, muscles, etc. which exist in him. The bone structure, the muscular structure, the nerve structure, the heart, lungs, etc. correspond to the living human being and are as such true and real. But when I look upon the corpse, this no longer corresponds to the living human being. The form which lies before me as corpse, no longer requires the existence of lungs, of a heart, or of a muscular system. Consequently these decay. For a while they maintain the form given to them, but a corpse is really an untruth, for it cannot exist in the form in which it lies before us; it must dissolve. It is not a reality. Similarly the things I perceive when I dig a hole into the earth are not realities. The closed earth influences the human being standing upon it, differently from the things which exist in such a way that when the human being stands upon the earth, he beholds them through his senses, as the earth's environment. If, to begin with, you consider this from the soul aspect, you may say: The earth's environment is able to influence man's senses and it may be grasped by the thinking or representing capacity pertaining to ordinary human consciousness. Also what is inside the earth exercises an influence upon man, but it does not follow the horizontal direction; it rises from below. In our ordinary state of consciousness, we do not perceive these influences rising from below in the same way in which we perceive the earth's environment through the ordinary senses. If we could perceive what rises up from the earth in the same way in which we perceive what exists in the earth's environment, we would need a kind of eye or organ of touch able to feel into the earth, without our having to dig a hole into it, so that we could reach or see through (durchgreifen) the earth in the same way in which we see through air when we behold something. When we look through air, we do not dig a hole into it; if we first had to dig a hole into air, in order to look at it, we would see our environment in the same way in which we would see the earth in a coal mine. Hence, if it were not necessary to dig a hole into the earth in order to see its inside, we would have to have a sense organ able to see without the need of digging holes into the earth, an organ for which the earth, such as it is, would become transparent to sight or touch. In a certain way this is the case, but in ordinary life these perceptions do not reach human consciousness. For what the human being would then perceive are the earth's different kinds of metals. Consider how many metals are contained in the earth. Even as you have perceptions in your air-environment—if I may use this expression—even as you see animals, plants, minerals, artistic objects of every kind, so perceptions of the metals rise up to you from the earth's inside. But if perceptions of the metals could really reach your consciousness, they would not be ordinary perceptions, but imaginations. And these imaginations continually reach man, by rising up from below. Even as the visual impressions come, as it were, from the horizontal direction, so the radiations of metals continually reach us from below; yet they are not visual perceptions of the minerals, but something pertaining to the inner nature of minerals, which works its way up through us and takes on the form of imaginations or pictures. But the human being does not perceive these pictures; they are weakened. They are suppressed, as it were, because man's earthly consciousness is not able to perceive imaginations. They are weakened down to feelings. If, for example, I imagine all the gold existing in some way in the caverns of the earth, and so forth, my heart really perceives an image which corresponds to the gold in the earth. But this picture is an imagination, and for this reason ordinary human consciousness cannot perceive it, for it is dulled down to a life feeling, an inner vital feeling, which cannot even be interpreted, less still perceived, in its corresponding image. The same applies to the other organs, for the kidneys perceive in a definite image all the tin which exists in the earth, and so forth. All these impressions are subconscious and they do not appear in the general feelings that live in the human being. You may therefore say: The perceptions coming from the earth's environment follow a horizontal direction and are met from within by the thinking or representing power; from below come the perceptions of metals—above all, of metals—and they are met by feeling, in the same way in which ordinary perceptions are met by the thinking capacity. This process, however, remains chaotic and unreal to the human beings of the present time. From these impressions they only derive a general life-feeling. If the human being on earth had the gift of imagination, he would know that his nature is also connected with the metals in the earth. In reality, every human organ is a sense organ, and although we use it for another purpose, or apparently do so, it is nevertheless a sense organ. During our earthly life, we simply use our organs for other purposes. For we really perceive something with each organ. The human being is in every way a great sense organ, and as such, he has differentiated, specified sense organs in the single organs of his body. You therefore see that from below, the human being obtains perceptions of metals and that he has a life of feeling corresponding to these perceptions. Our feelings exist in contrast to everything coming to us from the earth's metals, even as our thinking or representing power exists in contrast to everything which penetrates into our sense perceptions from the earth's environment. But in the same way in which the influences of the metals reach us from below, so we are influenced from above by the movements and forms of the celestial bodies in the world's spaces. We have sense perceptions in our environment, and similarly we have a consciousness which would manifest itself as inspired consciousness, as inspirations coming from every planetary movement and from every constellation of fixed stars. Even as our thinking capacity streams towards our ordinary sense perceptions, so we send out to the movements of the celestial bodies a force which is opposed to the impressions derived from the stars, and this force is our will. What lies in our will power, would be perceived as inspiration, if we were able to use the inspired state of consciousness. You therefore see that by studying man in this way, we must say to ourselves: In his earthly consciousness we find, to begin with, the condition in which he is most widely awake: his life of sensory perceptions and of thoughts. During our ordinary, earthly state of consciousness, we are completely awake only in this life of sensory perceptions and thoughts. Our feeling life, on the other hand, only exists in a dreaming state. There, we only have the intensity or clearness of dreams, but dreams are pictures, whereas our feeling life is the general soul constitution determined by life; that is to say, feeling. But at the foundation of feeling lie the metal influences coming from the earth. And the consciousness based on the will lies still deeper. I have frequently explained this. Man does not really know the will that lives in him. I have often explained this by saying: The human being has the thought of stretching out his arm, or of touching something with his hand. He can have this thought in his waking consciousness and may then look upon the process of touching something. But everything that really lies in between, the will which shoots into his muscles, etc., all this remains concealed to our ordinary consciousness, as deeply hidden as the experiences of a deep slumber without dreams. We dream in our feelings and we sleep in our will. But the will which sleeps in our ordinary consciousness responds to the impressions coming from the stars, in the same way in which our thoughts respond to the sense impressions of ordinary consciousness. And what we dream in our feelings is the counter-activity which meets the influences coming from the metals of the earth. In our present waking life on earth, we perceive the objects around us. Our thinking capacity counteracts. For this we need our physical and etheric body. Without the physical and etheric body we could not develop the forces which work in a horizontal direction—the perceptive and thinking forces. If we imagine this schematically we might say: As far as our daytime consciousness is concerned, the physical and etheric bodies become filled with sense impressions and with our thinking activity. When the human being is asleep, his astral body and his Ego organization are outside. They receive the impressions which come from below and from above. The Ego and the astral body really sleep in the metal streams rising up from the earth, if I may use this expression, and in the streams descending from the planetary movements and the constellations of fixed stars. What thus arises in the earth's environment exercises no influence in a horizontal direction, but exists in form of forces which descend from above, and in the night we live in them. If you could attain the power of imagination by setting out from your ordinary consciousness, so that the imaginative consciousness would really exist, you would have to achieve this in accordance with the demands of the present epoch of human development; namely, in such a way that every human organ is seized by the imaginative consciousness. For example, it would have to seize not only the heart, but every other organ. I have told you that the heart perceives the gold which exists in the earth. But the heart alone could never perceive the gold. This process takes place as follows: As long as the Ego and astral body are connected with the physical and etheric bodies, as is normally the case, the human being cannot be conscious of such a perception. Only when the Ego and the astral body become to a certain extent independent, as is the case in imagination, so that they do not have to rely on the physical and etheric bodies, we may say: The astral body and the Ego organization acquire, near the heart, the faculty of knowing something about these radiations coming from the metals in the earth. We may say: The center in the astral body for the influences which come from the gold radiations, lies in the region of the heart. For this reason we may say: The heart perceives—because the real perceptive instrument in the astral body pertaining to this part, to the heart—not the physical organ, but the astral body, perceives. If we acquire the imaginative consciousness, the whole astral body and also the whole Ego organization must enable the parts corresponding to every human organ to perceive. That is to say, the human being is then able to perceive the whole metal life of the earth—differentiated, of course. But details in it can only be perceived after a special training, when he has passed through a special occult study, enabling him to know the metals of the earth. In the present time, such a knowledge would not be an ordinary one. And today it should not be applied to life in a utilitarian way. It is a cosmic law that when the knowledge of the earth's metals is used for utilitarian purposes in life, this would immediately entail the loss of the imaginative knowledge. Last part—It may, however, occur that owing to pathological conditions, the intimate connection which should exist between the astral body and the organs is interrupted somewhere in man's being, or even completely, so that the human being sleeps, as it were, quite faintly, during his waking condition. When he is really asleep, his physical body and his etheric body on the one hand, and his astral body and his Ego on the other, are separated; but there also exists a sleep so faint that a person may walk about in an almost imperceptible state of stupor—a condition which may perhaps appear highly interesting to some, because such people have a peculiarly “mystical” appearance; they have such mystical eyes and so forth. This may be due to the fact that a very faint sleeping state exists even during the waking condition. There is always a kind of vibration between the physical and etheric body and the Ego organization and astral body. There is an alternating vibration. And such people can be used as metal feelers—they feel the presence of metals. But the capacity to feel the presence of special metal substances in the earth is always based on a certain pathological condition. Of course, if these things are only viewed technically and placed at the service of technical-earthly interests, it is, cruelly speaking, quite an indifferent matter whether people are slightly ill or not; even in other cases, one does not look so much at the means for bringing about this or that useful result. But from an inner standpoint, from the standpoint of a higher world conception, it is always pathological if people can perceive not only horizontally, in the environment of the earth, but also vertically, in a direct way, not through holes. What thus comes to expression, must, of course, be revealed in a different way. If we take a pen and write down something, this is contained in the ordinary life of thought; this must be lifeless. But the ordinary life of thought drowns in light (“verleuchtet”)—if I may use this expression in contrast to “darkens” (“verdunkelt”)—the perception coming from below; consequently, it is necessary to use different signs from those we use, for example, when we write or speak; different signs must be used when specific metal substances in the earth are perceived through a pathological condition. I observe, for example, that also water is a metal. Pathological people may actually be trained, not only to have unconscious perceptions, but also to give unconscious signs of these perceptions—for example, they can make signs with a rod placed in their hand. What is the foundation of all this? It is based on the fact that there is a faint interruption between the Ego and astral body on the one hand, and the physical and etheric body on the other, so that the human being does not only perceive what is, approximately speaking, at his side, but by eliminating his physical body he becomes a sensory organ able to perceive the inside of the earth, without having to dig holes into it. But when this direction exercises its influence, a direction which is normally that of feeling, then one cannot use the expressions which correspond to the thinking capacity. These perceptions are not expressed in words. They can only be expressed, as already indicated, through signs. Similarly, it is possible to stimulate perceptions descending from above. They have a different inner character; they are no longer a perception of metals, but inspiration, conveying the movements or the constellation of the stars. In the same way in which the human being perceives the earth's constitution as rising up from below, he now perceives, descending from above, something which again arises through pathological conditions, when the Ego is in a more loose connection with the astral body. He then perceives, descending from above, something which really gives the world its division of time, the influence of time. This enables him to look more deeply into the world's course of events, not only in regard to the past, but also in connection with certain events which do not flow out of man's free will, but out of the necessity guiding the world's events. He is then able to look, as it were, prophetically into the future. He casts a gaze into the chronological order of time. With these things I only wished to indicate that through certain pathological conditions it is possible for man to extend his perceptive capacity. In a s o u n d and h e a l t h y way this is done through imagination and inspiration. Perhaps the following may explain what constitutes sound and unsound elements in this field. For a normal person it is quite good if he has—let us say—a normal sense of smell. With a normal sense of smell he perceives objects around him through smell; but if he has an abnormal sense for any smelling object in his environment, he may suffer from an idiosyncrasy, when this or that object is near him. There are people who really get ill when they enter a room in which there is just one strawberry; they do not need to eat it. This is not a very desirable condition. It may, however, occur that someone who is not interested in the person, but in the discovery of stolen strawberries, or other objects which can be smelled, might use the special capacity of that person. If the human sense of smell could be developed like that of dogs, it would not be necessary to use police dogs, for people could be used instead. But this must not be one. You will therefore understand me when I say that the perceptive capacity for things coming from below and from above should not be developed wrongly, so as to be connected with pathological conditions, for these are positively destructive for man's whole organization. To train people to sense the presence of metals would therefore be the same as training them to be bloodhounds, police dogs, except that here—if I may use this expression—the humanly punishable element is far more intensive. For only through pathological conditions can such things appear in this or that person. All the things which generally come towards you in an ignorantly confused and nebulous way, will be understood in regard to their theory, and also by judging them as they have to be judged, within man's whole connection with the world. This is one aspect of the matter. The other aspect is that there is also a right application of such a knowledge. A person who is endowed with the imaginative power of knowledge, must not use the imaginative forces of the astral body, located in the region of the heart, to procure gold. He may, however, apply these forces to recognize the construction, the true tasks, the inner essence of the heart itself. He may apply them in the meaning of human self-knowledge. In physical life this also corresponds to the right application of—let us say—the sense of smell, of sight, and so forth. We learn to know every organ in man when we are able to put together what we discern as coming from below or from above. For example, you learn to know the heart when you recognize the gold contained in the earth, which sends out streams that may be perceived by the heart, and when, on the other hand, you recognize the current of will descending from the sun; that is to say, when you recognize the counter-current of the sun current in the will. If you unite these two streams, the joint activity of the sun's current from above, streaming down from the sun's zenith, and of the gold perceived below—if the gold contained in the earth stirs your imagination, and the sun your inspiration, you will obtain knowledge of the human heart, heart knowledge. In a similar way it is possible to gain knowledge of the other organs. Consequently, if the human being really wants to know himself, he must draw the elements of this knowledge from the influences coming from the cosmos. This leads us to a sphere which indicates even more concretely than I have done on previous occasions man's connection with the cosmos. If you add to this the lectures which I have just concluded on the development of natural science in more recent times, you will gather, particularly from yesterday's lecture, that on the present stage of natural science man learns to know essentially lifeless substance, dead matter. He does not really learn to know himself, his own reality, but only his lifeless part. A true knowledge of man can only arise from the joint perception of the lifeless organs which we recognize in man, the organs in their lifeless state, and all we are able to recognize from below and from above in connection with these organs. This leads to a knowledge based on full consciousness. An earlier, more instinctive knowledge was based upon an interpolation of the astral body which was different from that of today. Today the astral body is interpolated in such a way that man, as an earthly human being, may become free. This entails that he should recognize in the first place what is dead, and this pertains to the present, then the life foundation of the past through that which rises up from below—from the earth's metals—and finally the life-giving forces descending from above as star influences and star constellations. A true knowledge of man will have to seek in every organ this threefold essence: the lifeless or physical, the basis of life or the psychical, and the life-giving, vitalizing forces, or the spiritual. Everywhere in human nature, in every detail connected with it, we shall therefore have to seek the physical-bodily, the psychical, and the spiritual. Logically, its point of issue will have to be gained from a true estimate of the results so far obtained in the field of natural science. It is necessary to see that the present stage of natural science leads us everywhere to the grave of the earth and that the living essence must be discovered and lifted out of the earth's grave. We discover this by perceiving that modern spiritual science must endow old visions and ideas (Ahnungen) with life. For these always existed. In these days I have given advice to people working in different spheres; I would advise those studying history of literature that when they speak of Goetheanism, they should keep to Goethe's ideas expressed in the second part of “Wilhelm Meister”, in “Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahren”, where we find the description of a woman who is able to participate in the movements of the stars, owing to a pathological condition of soul and spirit. At her side we find an astronomer. And she is confronted by another character, by the woman who is able to feel the presence of metals. And at the side of this woman we find Montanus, the miner, the geologist. This contains a profound foreboding, far profounder than the truths in physics discovered since Goethe's time in the field of natural-scientific development, great as they are, for these natural-scientific truths pertain to man's circumference. But in the second part of “Wilhelm Meister” Goethe drew attention to something pertaining to the worlds with which man is connected—with the stars above, with the earth's depths below. Many things of this kind may be found, both in the useful fields and in the luxury fields of science. But also these things will only be drawn to the surface as real treasures of knowledge, when Goetheanism, on the one hand, and spiritual science on the other, will be taken so earnestly that many things of which Goethe had an inkling will be illumined by spiritual science; and also spiritual science may thus change into something giving us a historical sense of pleasure when we see that Goethe had a kind of idea of things which now arise in form of knowledge, and which he elaborated artistically in his literary works. With all these things, however, I wish to point out that when we speak of scientific strivings within the anthroposophical movement, these should be followed with that deep earnestness which does not bring with it the danger of Anthroposophy being deduced from modern chemistry, or modern physics, modern physiology, and so forth, but which includes the single branches of science in the real stream of living anthroposophical knowledge. One would like to hear of chemists, physicists, physiologists, medical men speaking in an anthroposophical way. For it leads to no progress if specialists succeed in forcing anthroposophy to speak chemically, physically or physiologically. This would only rouse opposition, whereas there should at last be a progress, evident in the fact that Anthroposophy reveals itself as Anthroposophy also to these specialists, and not as something which is taken in accordance with its terminology, so that terminologies are thrown over things which one already knows, even without Anthroposophy. It is the same whether anthroposophical or other terminologies are applied to hydrogen, oxygen, etc., or whether one adheres to the old terminologies. The essential thing is to take in Anthroposophy with one's whole being, then one becomes a true Anthroposophist, also as a chemist, physiologist, physician, etc. In these lectures, in which I was asked to describe the history of scientific thought, I wished to bring, on the basis of a historical contemplation, truths that may bear fruit. For the anthroposophical movement absolutely needs to become fruitful, really fruitful, in many different fields. |

| 11. Atlantis and Lemuria: Our Atlantean Forefathers

Tr. Max Gysi Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| An illustration of this may be given as follows: Let us think of a grain of corn; in it slumbers a force; this force acts in such a way that out of the grain of corn the stalk sprouts forth. |

| Under conditions like these, personal experience won for itself more and more importance in the third sub-race. When one group of human beings severed itself from another group, it brought with it for the foundation of its new community the vivid recollection of what it had experienced in its former surroundings. |

| Thus in the sixth sub-race must be sought the origin of law and legislation. And during the third sub-race the segregation of a group of human beings took place only when in a manner they were compelled to leave, because they no longer felt comfortable within the prevailing conditions, brought about by recollection. |

| 11. Atlantis and Lemuria: Our Atlantean Forefathers

Tr. Max Gysi Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Our Atlantean ancestors differed more from the men of to-day than may be imagined by anyone who is wholly limited to the world of sense for his knowledge. This difference extends not only to the outward appearance, but also to mental capacities. Their science and also their technical arts, their whole civilisation, differed much from that of our day. If we go back to the early times of Atlantean humanity we shall find there a mental capacity altogether different from our own. Logical reasoning, the calculatory combinations upon which all that is produced at the present day is based, were entirely wanting in the early Atlanteans, but in place of these they possessed a highly-developed memory. This memory was one of their most prominent mental faculties. For example, they did not count as we do by the application of certain acquired rules. A multiplication table was something absolutely unknown in early Atlantean times. No one had impressed upon his understanding the fact that three times four were twelve. A person's ability to make such a calculation, when necessary, rested on the fact that he could remember cases of the same or a similar kind. He remembered how this was done on former occasions. Now it must be clearly understood that whenever a new faculty is developed in a being, an old one loses its force and precision. The man of the present day has the advantage over the Atlantean of possessing a logical understanding and an aptitude for combination; but on the other hand his memory power has waned. We now think in ideas, the Atlantean thought in pictures; and when a picture rose in his mind he remembered many other similar pictures which he had formerly seen, and then formed his judgment accordingly. Consequently all education then was quite different from that of later times. It was not intended to provide the child with rules or to sharpen his wits. Rather was life presented to him in comprehensive pictures, so that subsequently he could call to remembrance as much as possible, when dealing with this or that circumstance. When the child had grown up and had reached maturity, he could remember, no matter what he might have to do, that something similar had been shown to him in the days of his instruction. He saw clearly how to act when the new event resembled something already seen. When absolutely new conditions arose, the Atlantean found himself compelled to experiment; while the man of to-day is spared much in this direction, being furnished with a set of rules which he can easily apply in circumstances new to him. Such a system of education gave a strong uniformity to the entire life. Things were done again and again in exactly the same way during very long periods of time. The faithfulness of memory offered no scope for anything at all approaching the rapidity of our own progress. A man did what he had always seen done before; he did not think, he remembered. Not he who had learnt much was held as an authority, but he who had experienced a great deal and could therefore remember much. It would have been impossible in Atlantean times for anyone who had not reached a certain age to be called upon to decide on any affair of importance. Confidence was placed only in one who could look back on a long experience. What is here said does not refer to Initiates and their schools, for they indeed are beyond the average development of their time. And for admission into such schools, age is not the deciding factor, but rather the consideration, whether the candidate in his former incarnations has acquired the ability to assimilate the higher wisdom. The confidence placed in Initiates and their agents in Atlantean times was not based on the extent of their personal experience, but on the age of their wisdom. For an Initiate, his own personality has ceased to have any importance; he is entirely at the service of the Eternal Wisdom, and therefore the characteristics of any period of time have no weight with him. Thus, while the power of logical thinking was still wanting, especially in the earlier Atlanteans, they possessed in their highly developed power of memory something which gave a special character to their whole activity. But other powers are always bound up with the nature of one special human force. Memory is nearer to the deeper foundations laid by Nature in man than is the power of reason; and in connection with the former, other impulses were developed which bore greater resemblance to those lower nature forces than the motive forces of human action at the present day. Thus the Atlantean was master of what is called the Life-Force. Just as we now draw from coal the force of warmth, which is changed into the force of propulsion in our methods of traffic, so did the Atlanteans understand how to use the germinal force of living things in the service of their technical works. An illustration of this may be given as follows: Let us think of a grain of corn; in it slumbers a force; this force acts in such a way that out of the grain of corn the stalk sprouts forth. Nature can awaken this sleeping force in the grain, but the man of to-day cannot do so at will. He must bury the grain in the earth, and leave its awakening to the forces of Nature. The Atlantean could do something more. He knew what to do in order to transform the force in a heap of corn into mechanical power, just as the man of our day can transform into a like power the force of warmth in a heap of coal. In Atlantean times plants were not cultivated merely for use as food, but also in order that the slumbering force in them might be rendered serviceable to their commerce and industry. Just as we have contrivances for transforming the latent force of coal into the power to propel our engines, so had the Atlanteans devices for heating by the use of plant-seeds in which the life-force was changed into a power applicable to technical purposes. In this way were propelled the air-ships of the Atlanteans, which soared a little above the earth. These air-ships sailed at a height rather below that of the mountains of Atlantean times, and they had steering appliances, by means of which they could be raised above these mountains. We must picture to ourselves that with the advance of time all the conditions of our earth have greatly changed. These air-ships of the Atlanteans would be quite useless in our days. Their utility lay in the fact that at that time the atmosphere enveloping our earth was much denser than now. Whether, according to the scientific conceptions of the present day, such an increased density of the air can be easily conceived, need not concern us here. Science and logical thought can never, from their very nature, determine what is possible and what impossible. Their task is only to explain what has been proved by experience and observation. And the density of the air here spoken of is, in occult experience, as much a certainty as any given fact of the world of sense can be to-day. And just as firmly established is the fact—perhaps even more inexplicable to the physics and chemistry of our time—that in those days the water over the whole earth was much more fluid than it is now. And owing to its fluidity, water (being driven by means of the life-force in seeds) could be used by the Atlanteans for technical purposes impossible to-day. On account of the densification of water, it has become impossible to set it in motion and to guide it in the same premeditated manner as was once possible. From this it is sufficiently evident that the civilisation of Atlantean times differed fundamentally from our own, and it will also be readily conceivable that the physical nature of an Atlantean was quite different from that of the contemporary man. Water when drunk by the Atlantean could be worked upon by the life-force within his own body in quite another way than is possible in the physical body of to-day. And thus it arose that the Atlantean could use his physical strength at will, quite otherwise than ourselves. He had, as it were, the means within himself of increasing physical forces when he required them for his own use. It is only possible to picture the Atlanteans correctly when one knows that they had conceptions of fatigue and the loss of strength absolutely different from our own. An Atlantean settlement, as may be gathered from what has already been said, bore a character in no way resembling that of a modern town. But there was a much closer resemblance between it and Nature. We can only give a faint suggestion of the real picture when we say that in early Atlantean times—till about the middle of the third sub-race—a settlement resembled a garden in which the houses formed themselves out of trees whose branches were intertwined in an artistic manner. Whatever the hand of man fashioned at that time grew naturally in like manner. Man, too, felt himself entirely akin to Nature, and so it arose that his social instinct was quite different from our own. Nature is indeed the common property of all men; and whatever the Atlantean built up with Nature for its foundation, he regarded as common property, precisely as the man of to-day thinks it only natural to regard as his own private property that which his acuteness and his reason have produced. Anyone who familiarises himself with the idea that the Atlanteans were endowed with such mental and physical powers as have been depicted, will likewise learn to understand that at still earlier periods mankind presents an aspect which but very faintly reminds us of what we are accustomed to see to-day. And not only man, but Nature which surrounds him, has also changed enormously in the course of time. [With regard to the time-periods at which the conditions shown held sway, something more will be said in the course of these communications. For the present the reader is warned not be surprised if the few figures given him in the previous chapter seem to contradict what he finds elsewhere.] The forms of plant and animal have altered; the whole of terrestrial Nature has undergone a transformation. Regions of the earth which were formerly inhabited have been destroyed, and others have arisen. The forefathers of the Atlanteans lived on a part of the earth which has disappeared, the principal portion of which lay to the south of what is Asia to-day. In Theosophical literature they are called Lemurians. After passing through various stages of evolution the greater number fell into decadence. They became a stunted race, whose descendants, the so-called savages, inhabit certain portions of the earth even now. Only a small number of the Lemurians were capable of advancing in their evolution, and it was from these that the Atlantean Race developed. Still later something similar occurred. The great mass of the inhabitants of Atlantis fell into decadence; and the so-called Âryans, to which race belongs the humanity of our present civilisation, sprang from a small division of these Atlanteans. According to the nomenclature of the “Secret Doctrine,” Lemurians, Atlanteans, and Âryans are Root-Races of humanity. If we think of two such Root-Races preceding the Lemurian, and two following the Âryan in the future, we have altogether seven. The one always arises out of the other in the manner pointed out in the case of the Lemurian, Atlantean, and Âryan Races. And each Root-Race has physical and mental qualities entirely different from those of that which precedes it. While, for example, the Atlantean brought his memory and everything in connection with it to a high degree of development, the duty of the Âryan of the present is to develop thought-power and all that appertains thereto. But each Root-Race itself must pass through different stages, and these again are always sevenfold. At the beginning of a time-period belonging to a Root-Race, its leading characteristics appear in an immature state; they gradually reach maturity, and then at last decadence. Thus, the members of a Root-Race are divided into seven sub-races. However, it must not be imagined that one sub-race immediately disappeared on the development of a new one. On the contrary, every one of them continued to exist for a long time, while others flourished beside it. Thus there are always dwellers on the earth, living side by side, but showing the most varied stages of evolution. The first sub-race of the Atlanteans arose from a portion of the Lemurian Race which was greatly advanced and capable of further evolution. For instance, in this latter race the gift of memory showed itself only in its very earliest beginnings, and even so much did not appear until the latest stages of its evolution. It must be realised that a Lemurian could indeed make images of his experiences, but could not preserve them as recollections; he immediately forgot what he had pictured to himself. That, in spite of this, he lived to a certain extent a civilised life; for instance, that he possessed tools, erected buildings, and so on, was not due to his own imagination, but to an inner mental force which was instinctive. Yet we must not imagine an instinct similar to that which animals possess at the present time, but an instinct of another order. The first sub-race of the Atlanteans is called in Theosophical literature the Rmoahal. The memory of this race was especially derived from vivid sense-impressions. Colours which the eye had seen, tones which the ear had heard, continued to operate long within the soul. This was manifested in the fact that the Rmoahals developed feelings quite unknown to their Lemurian ancestors. For instance, adherence to that which had been experienced in the past constituted part of such feelings. Now the development of speech depended on that of memory. As long as man did not remember the past, there could be no narration of experiences by means of speech. And because the first rudiments of a memory appeared in the latest Lemurian period, it was only then possible that the ability to give names to things heard and seen could begin to appear. It is only those who have the faculty of recollection who can make any use of a name which has been given to an object; and consequently it was in the Atlantean period that speech found its development. And with speech a tie was formed between the human soul and things exterior to man, since he then produced the spoken word from within himself, and this spoken word appertained to the objects of the outer world. Through communication by means of speech a new bond also arose between man and man. All this, indeed, was still in an elementary form at the time of the Rmoahals; but nevertheless it distinguished them profoundly from their Lemurian ancestors. Now the forces in the souls of these first Atlanteans still retained something of the force of Nature. Man was then in a certain manner more nearly related to the Nature-spirits surrounding him than were his descendants. Their soul forces were more Nature forces than are those of the men of the present, and so, too, the spoken word which they uttered had something of the might of Nature. Not only did they name objects, but their words contained a power over things and over their fellow-creatures. The word of the Rmoahal possessed more than mere meaning; it had also power. When we speak of the magic force of words we indicate something which was a far greater reality at that time, and for those men, than it is for men of the present. When a Rmoahal pronounced a word, this word developed a force akin to that of the object designated by it. Hence it is that words had the power of healing at that time, and that they could hasten the growth of plants, tame the rage of animals, and produce other such effects. All this force gradually faded away among the later Atlantean sub-races. It might be said that that fullness of strength which was a product of Nature wasted away little by little. The men of the Rmoahal race regarded such fullness of strength altogether as a gift from mighty Nature herself; and this relation of theirs with Nature bore for them a religious character. Speech was, to them, something especially sacred, and the misuse of certain tones in which dwelt a significant power was to them an impossibility. Every individual felt that such misuse must bring him terrible injury. The magic of such words, they thought, would change into its opposite; that which rightly used would cause a blessing would bring the author to ruin if wrongly employed. In a certain innocence of feeling the Rmoahals ascribed their power less to themselves than to Divine Nature working in them. It was otherwise in the second sub-race (the so-called Tlavatli peoples). The men of this race began to feel their own personal value. Ambition, an unknown quality among the Rmoahals, showed itself in them. We might say that the faculty of memory grew into the comprehension of life in communities. He who could look back on certain deeds demanded from his fellow-men some recognition of his ability. He claimed that his work should be held in remembrance, and it was this memory of deeds that was the basis on which rested the election, by a group of men allied to each other, of a certain one as leader. A kind of kingship arose. Indeed, this recognition extended beyond death. The remembrance, the commemoration of forefathers, or of those who, during life, had one merit, arose in this way, and thus in single family groups there grew up a kind of religious reverence for the dead—in other words, ancestor-worship. This has continued to spread into much later times and has taken the most varied forms. Among the Rmoahals a man was still esteemed only according to the degree in which for the moment he was able to make himself valuable by the greatness of his power. Did anyone want recognition for what he had done in former days, then he must show by new deeds that he still possessed the old power. He must call to remembrance his old achievements by the performance of new ones. That which had once been done was valueless in itself. Not until the second sub-race was the personal character of a man of so much account that his past life was taken into consideration in the estimation of it. A further result of the power of thought in drawing men to live together appeared in the fact that groups of men were formed who were united by the remembrance of deeds done in company. The forming of such groups originally depended wholly upon the forces of Nature, on their common parentage. By his own intelligence man had as yet added nothing to that which Nature had made of him. One mighty personality now enlisted a great company to share in a common undertaking; and the remembrance of this work, being retained by all, built up a social group. This manner of living together in social groups only impressed itself forcibly when the third sub-race (the Toltec) was reached. It was therefore the men of this race who first founded what may be called a commonwealth, the earliest kind of statecraft. The leadership, the government, of this commonwealth passed from ancestors to descendants. That which had formerly continued only in the memory of their fellow-men, the father now transferred to the son. The deeds of their forefathers would be kept in remembrance by the whole race. The achievements of an ancestor continued to be cherished by his descendants. However, we must clearly understand that in those times men really had the power to transfer their gifts to their offspring. Education was based upon the representation of life in comprehensive pictures, and the efficacy of this education depended on the personal force which proceeded from the teacher. It was not an intellectual power which he sought to excite, but rather those gifts which were more instinctive in character. By such a system of education the father's ability was really, in most cases, transferred to the son. Under conditions like these, personal experience won for itself more and more importance in the third sub-race. When one group of human beings severed itself from another group, it brought with it for the foundation of its new community the vivid recollection of what it had experienced in its former surroundings. But all the same, these memories contained something with which they were not in sympathy, something in which they did not feel at ease. In this connection, therefore, they sought something new, and thus conditions improved with every new settlement of the kind. And it was only natural that the improved conditions should find imitators. These were the facts on which rested the foundation of those flourishing commonwealths that arose in the time of the third sub-race, and are described in Theosophical literature. The personal experiences undergone found support from those who were initiated into the eternal laws of mental development. Mighty rulers received initiation in order that personal ability might have its full provision. A man gradually prepares himself for initiation by his personal ability. He must first develop his forces from below upwards, so that enlightenment may then be imparted to him from above. Thus arose the King-Initiates and Leaders of the people among the Atlanteans. In their hands lay a tremendous amount of power, and great, too, was the reverence paid to them. But in this fact lay also the cause of their fall. The development of memory led to enormous personal power. The individual began to wish for influence by means of this power of his; and the greater the power grew, the more did he desire to use it for himself. The ambition which he had developed became selfishness, and this gave rise to a misuse of forces. When we consider what the Atlanteans were able to do by their command of the life-force, we can understand that such misuse must have had tremendous consequences. An enormous power over Nature could be placed at the service of personal self-love. And this was what happened in full measure during the period of the fourth sub-race (the original Turanians). The members belonging to this race, who were instructed in the mastery of the forces mentioned, made manifold use of these to satisfy their wayward wishes and desires. But these forces put to such a use naturally destroy one another in their action. It is as if the feet of a man wilfully moved forwards while at the same time the upper part of his body desired to go backwards. Such destructive action could only be arrested by the cultivation of a higher force in man. This was thought-power. The effect of logical thinking is to restrain selfish personal wishes. We must seek the origin of this logical thought in the fifth sub-race (the original Semites). Men began to go beyond the simple remembrance of the past, they began to compare their various experiences. The faculty of judgment developed, and wishes and desires were regulated according to this discernment. Man began to calculate, to combine. He learnt to work in thoughts. Whereas formerly he had abandoned himself to every wish, he now asked himself whether, on reflection, he approved of the wish. While the men of the fourth sub-race wildly rushed after the satisfaction of their desires, those of the fifth began to hearken to the inner voice. And this inner voice had the effect of checking the desires, even if it could not crush the demands of the selfish personality. Thus did the fifth sub-race implant within the human soul the interior impulses of action. In his own soul man must decide what to do and what to leave undone. But, while man thus gained thought-power inwardly, his command over the external forces of Nature was being lost. The forces of the mineral kingdom can be controlled only by means of this combining thought, not by the life-power. It was therefore at the cost of the mastery of the life-force that the fifth sub-race developed thought-power. But it was just by so doing that they created the germs of a further evolution of humanity. Now it is no longer possible for thought alone, working entirely within the man, and no longer able to command Nature directly, to bring about such devastating results as did the misused forces of earlier times, even if the personality, self-love, and selfishness were ever so great. Out of this fifth sub-race was chosen its most gifted portion, which outlived the destruction of the Fourth Race and formed the nucleus of the Fifth,—the Âryan race, whose task it is to bring to perfection the power of thought and all that belongs thereto. The men of the sixth sub-race—the Akkadian—trained their thought-power still more highly than did the fifth. They distinguished themselves from the so-called original Semites by bringing into use in a wider sense the faculty mentioned. It has been said that the development of thought-power did not indeed allow the demands of the selfish personality to attain such destructive results as were possible in earlier races; but that, nevertheless, these demands were not killed out by it. The original Semites at first regulated their personal affairs as their reason suggested. In place of crude desires and lust, prudence appeared. Other conditions of life presented themselves. Whereas the races of former times inclined to recognize as their leader him whose deeds were deeply engraved in the memory, or who could look back on a life rich in recollections, such a rôle was now rather adjudged to the wise man; and if formerly that was considered decisive which was still fresh in the memory, so now that was regarded as best which appealed most strongly to the reason. Under the influence of thought men once clung to a thing till it was considered insufficient, and then in the latter case it came about naturally that he who had a novelty capable of supplying a want should find a hearing. A love of novelty and a longing for change were, however, developed by this thought-power. Everyone wanted to carry out what his own sagacity suggested; and thus it is that restlessness begins to appear in the fifth sub-race, leading in the sixth to the necessity of placing under general laws the capricious ideas of the single individual. The glory of the states of the third sub-race lay in the order and harmony caused by a common memory. In the sixth this order had to be obtained by deliberately constructed laws. Thus in the sixth sub-race must be sought the origin of law and legislation. And during the third sub-race the segregation of a group of human beings took place only when in a manner they were compelled to leave, because they no longer felt comfortable within the prevailing conditions, brought about by recollection. It was essentially different in the sixth. The calculating power of thought sought novelty as such; it urged men to enterprise and new undertakings. Thus the Akkadians were an enterprising people inclined towards colonization. It was commerce especially that fed the young and germinating power of thought and judgment. In the seventh sub-race—the Mongolian—thought-power also developed; but in them existed qualities of the earlier sub-races, especially of the fourth, in a much greater degree than in the fifth and sixth. They remained true to their sense of memory. And so they came to the conclusion that the most ancient must also be the wisest, must be that which could best defend itself against the attack of thought. They had indeed lost the command of the life-force, but that which developed in them as thought-power had in itself something of the power of this life-force. It is true they had lost the power over life, but never the direct, instinctive belief in the existence of such a power. This force, indeed, became to them their God in Whose service they performed everything which they considered right. Thus they appeared to their neighbours to be possessed of a mystic power, and the latter yielded to it in blind faith. Their descendants in Asia and in some European regions showed, and still show, much of this peculiarity. The power of thought implanted in man could only attain its full value in evolution when, in the Fifth Race, it acquired a new impulse. After all, the Fourth could only place this power at the service of that which had been fostered by the gift of memory. It was not until the Fifth was reached that such forms of life were attained as could find their instrument in the faculty of thought. |

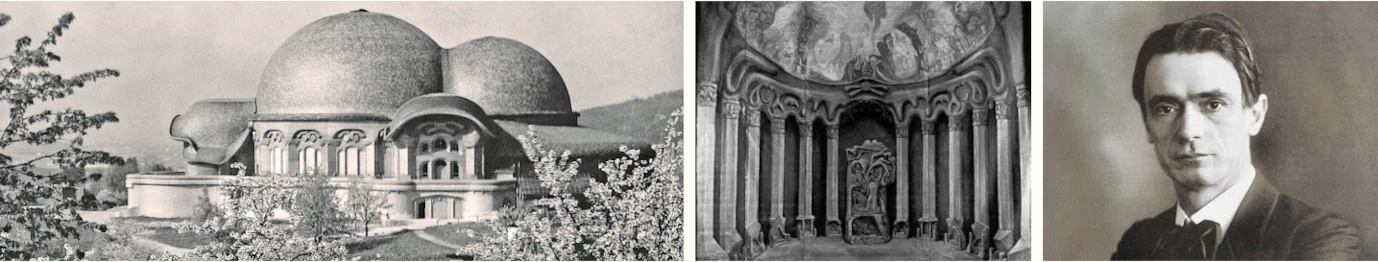

| 287. The Building at Dornach: Lecture I

18 Oct 1914, Dornach Tr. Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| For hours, that was the sole impression—but what was the truth of the matter? The truth was that an eloquent karma in the life of a human being was enacted; that this life so full of promise was in that moment karmically rounded off, having been required back in the worlds by the Spiritual Powers. |

| Sometimes possibly one can go further and say that external reports and documents actually hinder our recognition of the true course of history. That is more particularly so if—as happens in nearly every epoch—the documents present the matter one-sidedly and if there are no documents giving the other side, or if these are lost. |

| If we call to our aid all the anthroposophical endeavours now at our disposal, we can readily understand that human lives which are prematurely torn away—which have not undergone the cares and manifold coarsenings of life and pass on still undisturbed—are forces within the spiritual world which have a relationship to the whole of human life; which are there in order to work upon human life. |

| 287. The Building at Dornach: Lecture I

18 Oct 1914, Dornach Tr. Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

In the lectures which it has been my lot to deliver, I have often drawn attention to an observation which might be made in real life, and which shows the necessity of seeking everywhere below the surface of life's appearances, instead of stopping at first impressions. It runs somewhat as follows.—A man is walking along a river bank and, while still some way off, is seen to pitch headlong into the water. We approach and draw him out of the stream, only to find him dead; we notice a boulder at the point where he fell and conclude at first sight as a matter of course that he stumbled over the stone, fell into the river and was drowned. This conclusion might easily be accepted and handed down to posterity—but all the same it could be very wide of the mark. Closer inspection might reveal that the man had been struck by a heart-attack at the very moment of his coming up to the stone, and was already dead when he fell into the water. If the first conclusion had prevailed and no one had made it his business to find out what actually occurred, a false judgment would have found its way into history—the apparently logical conclusion that the man had met his death through falling into the water. Conclusions of this kind, implying to a greater or lesser degree a reversal of the truth, are quite customary in the world—customary even in scholarship and science, as I have often remarked. For those who dedicate themselves heart and soul to our spiritual-scientific movement, it is necessary not only to learn from life, but incessantly to make the effort to learn the truth from life, to find out how it is that not only men but also the world of facts may quite naturally transmit untruth and deception. To learn from life must become the motto of all our efforts; otherwise the goals we want to reach through our Building1 as well as in many other ways will be hard of attainment. Our aim is to play a vital part in the genesis of a world-era; a growth which may well be compared with the beginning of that era which sprang from a still more ancient existence of mankind—let us say the time to which Homer's epics refer. In fact, the entire configuration, artistic nature and spiritual essence of our Building attempts something similar to what was attempted during the happenings of that transitional period from a former age to a later one, as recounted by Homer. It is our wish to learn from life, and, what is more, to learn the truth from life. There are so very many opportunities to learn from life, if we wee willing. Have we not had such an opportunity even in the last day or two? Are we not justified in making a start with such symptoms, particularly with one that has so deeply moved us? Consider for a moment!2 On Wednesday evening last, many of our number either passed by the crossroads or were in the neighbourhood, saw the wagon overturned and lying there, came up to the lecture and were quite naturally, quite as a matter of course, aware of nothing more than that a cart had fallen over. For hours, that was the sole impression—but what was the truth of the matter? The truth was that an eloquent karma in the life of a human being was enacted; that this life so full of promise was in that moment karmically rounded off, having been required back in the worlds by the Spiritual Powers. For at certain times these Powers need uncompleted human lives, whose unexpended forces might have been applied to the physical plane, but have to be conserved for the spiritual worlds for the good of evolution. I would like to put it this way. For one who has saturated himself with spiritual science, it is a plainly evident fact that this particular human life may be regarded as one which the gods require for themselves; that the cart was guided to the spot in order that this karma might be worked out, and overturned in order to consummate the karma of this human life. The way in which this was brought home to us was heartrending, and rightly so. But we must also be capable of submerging ourselves in the ruling wisdom, even when it manifests, unnoticed at first, in something miraculous. From such an event we should learn to look more profoundly into the reality. And how indeed could we raise our thoughts more fittingly to that human life with which we are concerned, and how commemorate more solemnly its departure from earth, than by forthwith allowing ourselves to be instructed by the grave teaching of destiny which has come to us in these days. Yet it is a human trait to forget only too promptly the lessons which life insistently offers us! It is on this account that we have to call to our aid the practice of meditation, the exercise of concentrated thinking, in order to essay any comprehension of the world at all adequate to spiritual science; we must strive continually towards this. And I would like to interpose this matter now, among the other considerations relative to our Building, because it will serve as an illustration for what is to follow concerning art. For let us not hold the implications of our Building to be less than a demand of history itself—down to its very details. In order to recognise a fact of this kind in full earnest, it must be our concern to acquire the possibility, through spiritual science, of reforming our concepts and ideas, of winning through to better, loftier, more serious, more penetrating and profound concepts and ideas concerning life, than any we could acquire without spiritual science. From this standpoint let us ask the downright question What then is history, and what is it that men so often understand by history? Is not what is so often regarded as history nothing more at bottom than the tale of the man who is walking along a river's bank, died from a heart attack, falls into the water, and of whom it is told that he died through drowning? Is not history very often derived from reports of this kind? Certainly, many historical accounts have no firmer foundation. Suppose someone had passed by the cross-roads between 8 and 9 o'clock last Wednesday evening and had had no opportunity of hearing anything about the shattering event which had taken place there: he could have known nothing, only that a cart had been overturned, and that is how he would report it. Many historical accounts are of this kind. The most important things lying beneath the fragments of information remain entirely concealed; they withdraw completely from what is customarily termed history. Sometimes possibly one can go further and say that external reports and documents actually hinder our recognition of the true course of history. That is more particularly so if—as happens in nearly every epoch—the documents present the matter one-sidedly and if there are no documents giving the other side, or if these are lost. You may call this an hypothesis but it is no hypothesis, for what is taught as history at the present time rests for the most part upon such documents as conceal rather than reveal the truth. The question might occur at this point: How is any approach to the genesis of historical events to be won? In all sorts of ways spiritual science has shown us how, for it does not look to external documents but seeks to discern the impulses which play in from the spiritual worlds. Hence it naturally cannot describe the outward course of events as external history does, It recognises inward impulses everywhere. Moreover, the spiritual investigator must be bold enough, when tracing these impulses on the surface, to hold fast to them in the face of outer traditions. Courage with regard to the truth is essential, if we would take up our stand on the ground of spiritual science, The transition can be made by attempting to approach the secrets of historical “coming into being” otherwise than is usually done. Consider all the extant 13th and 14th century documents about Italy, from which history is so fondly composed. The tableau, the picture, obtained by thus assembling history out of such documents brings one far less close to the truth one can get by studying Dante and Giotto, and allowing what they created out of their souls to work upon one. Consider also what remains of Scholasticism, of its thoughts, and try to reflect upon, to reproduce in yourself, what Dante, Giotto and Scholasticism severally created—you will get a truer picture of that epoch than is to be had from a collection of external documents. Or someone may set himself the task of studying the rebellion of the Protestant spirit of the North or of Mid-Europe against the Catholicism of the South. What can you not find in documents! Yet it is not a question of isolated facts, but of uniting one's whole soul with the active, ruling, weaving impulses at work. You come to know this rising up of the Protestant spirit against the Catholic spirit through a study of Rembrandt and the peculiar nature of his painting. Much could be brought forward in this way. And so it comes about that historical documents are often more of a hindrance than a help. Perhaps the type of history bookworm who subsists upon documentary evidence would be elated by a pile of material on Homer's life, or Shakespeare's. From a certain point of view, however, one could say: Thank God there is no such evidence! We must only be wary not to exaggerate a truth of this kind, not to press it too far. We must indeed be grateful to history for leaving us no documents about Homer or Shakespeare. Yet something might here be maintained which is one-sidedly true—one sided, but true, for a one sided truth is nevertheless a truth. Someone might exclaim: How we must long for the time when no external documents about Goethe are available. Indeed, with Goethe it is often not merely disturbing, but an actual hindrance, to know what he did, not only from day to day but sometimes even from hour to hour. How wonderful it would be to picture for oneself the experience undergone by the soul of a man who at a particular time of life spoke the fateful words:

If one wished to find the answer oneself in the case of such men, one might well yearn for the time when all the Leweses, and so on, whatever their names may be, no longer tell us what Goethe did the livelong day in which this or that verse was set down. And what a hindrance in following the flight of Goethe's soul up to the time in which he inscribed these words:

What a hindrance it is that we are able to refer to the many volumes of his notebooks and correspondence, and to read how Goethe spent this period. This view is fully justified from one angle, but not from every angle; for although it is fully justified in the case of Homer, Shakespeare, and so on, it is one sided with regard to Goethe, since Goethe's own works include his “Truth and Poetry” (“Dichtung und Wahrheit”). An inherent trait of this personality is that something about it should be known, since Goethe felt constrained to make this personal confession in “Truth and Poetry”. Hence the time will never come when the poet of “Faust” will appear to humanity in the same light as the poet of the “Iliad” or the “Odyssey”. So we see that a truth brought home to us from one side only can never be given a general application; it bears solely on a particular, quite individual case. Yet the matter must he grasped still more profoundly. Spiritual science tries to do this. By pointing out certain symptoms, I have repeatedly endeavoured to show that modern culture aspires towards spiritual science. In my Rätsel der Philosophie3 I have tried to show how this is particularly true of philosophy. In the second volume you will notice that the development of philosophy presses on towards what I have sketched in the concluding chapter as “Prospect of an Anthroposophy”. That is the direction taken by the whole book. Of course this could not have been done without some support from our Anthroposophical Society, for the outer world will probably make little of the inner structure of the book as yet. I said that Goethe must be regarded differently from Homer. On the same grounds I would like to add: Do we then not come to know Homer? Could we get to know him by any better means than through his poems, although he lived not only hundreds but even thousands of years ago? Do we not get to know him far better in that way than we ever could from any documents? Yes, Homer's age was able to bring forth such works, through which the soul of Homer is laid bare. Countless examples could be given. I will mention one only one, however, which is connected with the deepest impulses of that turning-point during the Homeric age, much as we ourselves hope and long for in the change from the materialistic to the anthroposophical culture. We know that in the first book of the Iliad we are told of the contrast between Agamemnon and Achilles: the voices of these two in front of Troy are vividly portrayed. We know further that the second book begins by telling us that the Greeks feel they have stood before Troy quite long enough, and are yearning to return to their homeland. We know, too, that Homer describes the events as if the Gods were constantly intervening as guiding divine-spiritual powers. The intervention of Zeus is described at the beginning of this second book. The Gods, like the Greeks below, are sleeping peacefully; so peacefully, indeed, that Herman. Grimm, in his witty way, suggests that the very snoring of the heroes, of the Gods and of the Greeks below, is plainly audible. Then the story continues:

Zeus, then, sends the Dream down from Olympus to Agamemnon. He gives the Dream a commission, The Dream descends to Agamemnon, approaching him in the guise of Nestor, who we have just learned, is one of the heroes in the camp of the allies.

This, then, is what takes place. Zeus, the presiding genius in the events, sends a Dream to Agamemnon in order that he should bestir himself to fresh action. The Dream appears in the likeness of Nestor, a man who is one of the band of heroes among whom Agamemnon is numbered. The figure of Nestor, whose physical appearance is well-known to Agamemnon, confronts him and tells him in the Dream what he should do. We are further told that Agamemnon convenes the elders before he calls an assembly of the people. And to the elders he recounts the Dream just as it had appeared to him:

(Atreus' son then tells the elders what the Dream had said. None of the elders stands up excepting Nestor alone, the real Nestor, who utters the words:)