| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Building as a Setting for the Mystery Plays

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| They withdraw into the closed rooms of the laboratory and the observatory, and devote themselves to specialized investigations in these fields, but in so doing they distance themselves from a truly living understanding of the totality of the world. One withdraws as a human being from real cooperation with practical life, and as a result one arrives at a closed intellectuality. |

| For only from the human being in his head comes what modern language has created for our science and our popular literature, and what today's people, if you listen to them, are able to understand. You have to touch the deeper sides of their minds if you want to speak to them what anthroposophical spiritual science actually has to say. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Building as a Setting for the Mystery Plays

02 Oct 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

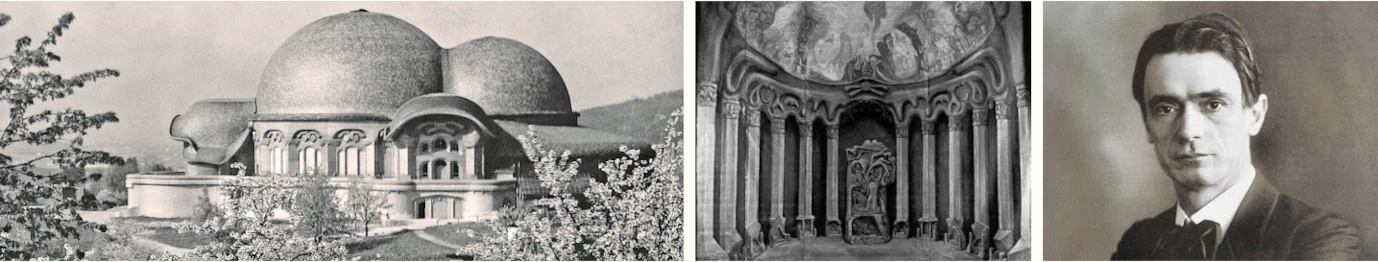

Over a period of three hours I shall have the opportunity of speaking to you about the building idea of Dornach. In this first lecture, it is my task to characterize how this building idea emerged from the anthroposophically oriented spiritual movement, and then, over eight days and in a fortnight, to go into more detail about the style and the whole formal language of this our building, the framework and the external representative of our spiritual scientific movement. By speaking about the genesis of the Dornach building, I would like to perhaps touch on something personal by way of introduction. I spent the 1880s in Vienna. It was the Vienna in which the ideas were developed that could then be seen in the Votivkirche, in the Vienna City Hall, in the Hansen Building of the Austrian Parliament, in the museums, in the Burgtheater building, that is to say in those monumental buildings that were created in Vienna in the second half of the last century and which, to a certain extent, represent the most mature products of the architecture of the past era of human development. I would like to say that I heard the words of one of the architects involved in these buildings resound from the views from which these monumental buildings were created. When I was studying at the Vienna Technical University, Heinrich Ferstel, the architect of the Votivkirche, had just taken up his post as rector. In his inaugural address, he said something that I would like to say still echoes in my mind today, and it has echoed throughout my subsequent life. Ferstel said something at the time that summarized the most diverse views that had emerged in art at the time, especially in the art of architecture. He said: architectural styles are not invented, architectural styles are born out of the overall views, out of the overall development of the time and the emotional soulfulness of entire peoples and eras. On the one hand, such a sentence is extremely correct, and on the other hand, it is extremely inflammatory for the human mind. And anyone who has ever immersed themselves with artistic sensibility in the whole world of vision from which this remarkable Gothic structure of the Votive Church in Vienna, translated into miniature, was created by Ferstel himself, anyone who has felt the Vienna City Hall by Schmidt, anyone who has felt the Austrian Parliament in particular, which, through Hansen's genius, has achieved a certain freedom of style, at the time when this same view had not yet been spoiled by the hideous female figure that was later placed on the ramp. Those who had experienced the artistic heyday of Gottfried Semper's mature architecture at the Vienna Burgtheater could truly feel the background from which such an artistic view emerged as that of Heinrich Ferstel, which has just been characterized. In all that was built, one sees ripe fruits, but basically one sees only the renewal of the styles of past epochs of humanity. And I was able to feel this, I would like to say, inwardly inciting fact, for example, when I heard the lectures of the excellent esthete Joseph Bayer, who, out of the same spirit that Ferstel, Hansen, cathedral architect Schmidt, but especially Gottfried Semper, created with, tried to illustrate the forms of architectural art, the forms of ceramics, and so on. Such a fact, such a world of ideas, is inspiring for the human mind, I say this because perhaps, when faced with such an idea, “architectural styles are not invented, but born out of an overall spiritual life” in the human mind - when one sees: this view has achieved something magnificent and powerful, but from a mere renewal, from a renaissance of old architectural styles, old artistic perceptions, so to speak - because then the question arises before the soul: Are we perhaps such a barren time after all that we cannot give birth to something new in this sense from our overall view, from the scope of our world view? At the same time as all that could so richly fill the souls from these buildings when they immersed themselves in these views, from which the buildings arose, something else, though characteristic of the time, was concentrated in Vienna. In its soul body, Vienna had at that time also absorbed a certain height of precisely the newer medical progress. Skoda, Oppolzer and others represented a flowering of the development of medical science in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, especially if you lived among those who had to deal with such things, you could often hear a saying – and this saying also stayed with me: We live in a time in which medical nihilism has developed. This medical nihilism, which had emerged precisely in the heyday of pathology, actually culminated in the fact that the great physicians mainly studied those forms of disease that could be observed in their course merely through pathology, in which nature's healing process only needed to be helped along by all sorts of measures, but in which little could be done for the patient by taking remedies. Thus, precisely out of this medical school arose a disbelief in therapy, a skepticism about therapy. And when pathology had developed to its highest peak that it could reach at that time, people actually despaired of the possibility of real healing and, especially in initiated circles, spoke of medical nihilism. That is what one could feel. Our world view, where it was to prove fruitful in a certain area of practical life, led to nihilism and a certain powerlessness in the face of that practical life. Anyone with the ability to feel and perceive these things will, in the subsequent period of European civilization, be able to fully sense how, basically, those impulses, which on the one hand found expression in the fact that an architect as important as Heinrich Ferstel had to say, “Architectural styles are not invented, but are born out of the overall development of the time,” and yet still built in the sense of an old architectural style, on the other hand, expressed itself in the fact that in a practical area of life, people's views have led to nihilism. What developed from this in the period that followed was basically a continuation of what had been expressed in this way. Through the most diverse circumstances, seemingly, but probably through a necessary connection, I was confronted with the necessity of setting up impulses of a new spiritual life everywhere in the face of the appearance of what lay in the lines of development I have indicated. This new spiritual life would in turn draw from such original sources of human thought , human feeling and human will, as they repeatedly existed in the epochs of human development and as they proved fruitful in order to give rise to the artistic, the religious and the cognitive. If we want to feel in an even deeper way what the human mind was actually like at a time when, in art, only a kind of renaissance was living in the highest expressions of the artistic, and when, even in practical areas, views have led to a kind of nihilism When we delve into what was actually taking place in the soul and spirit during this time, we have to say that the spiritual matters that directly concern the human being, the scientific, and even to a high degree the religious life, had taken on an abstract, intellectual character. Man had come to cultivate less that which can arise from his entire human essence, his powers and impulses. In this most recent period, he had come to establish a mere head culture, a mere intellectualistic culture, to live in abstractions. This is something that occurs as a parallel phenomenon in the materialistic age: on the one hand, people believe that they can completely immerse themselves in the workings of material processes; but on the other hand, precisely because of this striving for immersion in a tendency towards abstraction, a tendency towards mere intellectualism, a tendency through which the urge to shape something that can directly reach into the full reality of existence fades from the most intimate affairs of the human soul. One withdraws into an abstract corner of one's soul life, leaving one's religious feelings to take place there. They withdraw into the closed rooms of the laboratory and the observatory, and devote themselves to specialized investigations in these fields, but in so doing they distance themselves from a truly living understanding of the totality of the world. One withdraws as a human being from real cooperation with practical life, and as a result one arrives at a closed intellectuality. And finally, everything that we see emerging in the fields of philosophy or world view in this period bears a distinctly abstract, a distinctly intellectual character. I believed that anthroposophically oriented spiritual science had to be placed in this current. It was not surprising that this spiritual science, when it was first placed in an intellectualist age, when it had to speak to people who, in the broadest sense, were fundamentally oriented towards intellectualist abstraction, initially had to appear as a worldview as if it itself had arisen only from abstraction, from mere thinking. And so it was that in our work for our anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, that phase arose which filled the first decade of the twentieth century and of which I would like to say: it was inevitable that our anthroposophically oriented world view should take on a certain intellectual character through the very nature of the people who were inclined towards it. It had to speak to people who, above all, believed that if you wanted to ascend to the spiritual and divine, you had to do so completely detached from the lower reality, you even had to arm yourself with a certain world-contempt, with a certain unreality of life. This was already an attitude that was alive in those who, out of their inclinations, had found their way into the current of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. And on the other hand, the world's judgment of this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science arose: Oh, they are dreamers, they are visionaries, they are people who are not relevant to practical life. This judgment arose - such things are very difficult to destroy - and still lives on today in most people who want to judge anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Of course, people saw that something different was alive in what appeared at that time as this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science than in their theories, in their world-view ideas. And since they regarded what they had sucked out of their bloodless abstractions from their materialistic orientation as the only spiritual reality to be attained by man himself, what the anthroposophically oriented spiritual science spoke to the world from completely different foundations seemed to them to be something fanciful, something fantastic. But a quite different phenomenon was involved. What was spoken at that time out of truly shaped spiritual science oriented to anthroposophy is not the speech of fantasy or enthusiasm. It is the speech of spiritual research that can give an account of the nature of its research to the most exacting mathematician, as I said at another time. But it is true: what has been spoken here out of spiritual realities sounded different from the bloodless world views of modern times. It sounded different, not because it was more abstract, or because it ascended to regions of the spirit more bloodless and frozen than those which have given rise to the theories developed out of the modern way of thinking, but it sounded different because it proceeded from spiritual realities, because it proceeded from those regions of man where one not only thinks, where one feels and wills, but does not feel and will in a dark way, not in the way that modern psychology considers to be the only one because it only knows this; not out of dark feeling, but out of feeling that is just as bright, as bright as the purest thinking itself. And the words were spoken out of a will that is suffused with a light that is striven for as the bright clarity of pure thoughts is striven for, and these thoughts are grasped when we seek to comprehend reality. Thus, in this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, there lived that which wanted to come from the whole person, which therefore also wanted to take hold of the whole person, to take hold of the thinking, feeling and willing human being. When one was able to speak in this way from the innermost being of the whole person, one often felt the inadequacy of even modern modes of expression. Anyone who has felt this way knows how to speak about it. One felt that modern times had also brought something into external language that leads words into abstract regions, and that speaking in the way language has now become itself invites abstraction. And one experiences, I would say, the inwardly tragic phenomenon of carrying within oneself something that one would like to express in broad content and sharp contours and developed with inner life, but that one is then rejected back to what modern language, which is coming out of an age of abstraction and is theoretical, alone knows how to say. And then one feels the urge for other means of expression. One feels the urge to express oneself more fully about what one actually carries within oneself than can be done through the theoretical debates in which modern humanity has been trained for three to four centuries, the theoretical debates that have shaped our concepts, our words, in which even our lyricists, our playwrights, our epic poets live more than they realize. One feels the necessity for a fuller, more vivid presentation. Out of such feelings, the need arose for me to say what was said in the first phase of our anthroposophical movement, which was clothed in more intellectual forms, through my mystery festival plays. I tried to present, in a theatrical way, in scenes and images that were to embrace the whole of human life, the physical, soul and spiritual life, what can be seen in the course of the world, what is contained in the course of the world as a partial solution to our great world riddles, but which can never be expressed in the abstract formulas into which the laws of nature can be expressed. This is how that which I then tried to depict in my mystery dramas came about. I had to resort to images to depict what comes from the whole human being. For only from the human being in his head comes what modern language has created for our science and our popular literature, and what today's people, if you listen to them, are able to understand. You have to touch the deeper sides of their minds if you want to speak to them what anthroposophical spiritual science actually has to say. This is how the need for these mystery dramas arose. These mystery dramas were first performed in Munich, in the surroundings, in the setting of ordinary theaters. Just as it literally blew apart the inside of the soul when one had to express the anthroposophically oriented spiritual science in the formulas of modern philosophy or world view, so it blew apart one's aesthetic sensation when one had to present in an ordinary theater, in an ordinary stage space, what was now to be depicted in a pictorial way: the spiritual content of the anthroposophical worldview and world feeling, of the anthroposophical world will. And when we worked in Munich on the theatrical presentation of these mystery plays in ordinary theaters, the idea arose to create a space of our own, to perform a building of our own, in which there would no longer be the sense of confinement that one in the manner just described for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, but in which there is a framework that is itself the expression of what lives in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Therefore, this building was not created in the sense of an old architectural style, where one would have gone to any architect and had a house created for what anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is to work out, but rather it had to arise from the innermost being of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, because it did not merely work out of thinking and feeling, but out of the will itself, a structure had to arise out of this living existence of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science as a framework, which, as a style, as a formal language, gives the same as the spiritual-soul gives the spoken word of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. A unity had to be created between the building as an art form and the living element present in this spiritual science. But if there is such a living element, if there is a living element that is not merely theoretical and abstract, if there is a truly living spiritual element, then it creates its own framework, because with such a spiritual element one lives within the creative forces of nature, within the creative forces of the soul, within the creative forces of the spiritual. And just as the shell of the nut is formed out of the same creative forces as the inside, which we then consume as a nut, just as the nutshell cannot be other than it is because it follows the laws the nut kernel comes into being, so this structure here in all its individual forms is such that it cannot be otherwise, because it is nothing other than a shell that has come into being, been formed, created according to the same laws as spiritual science itself. If I may express myself hyperbolically, it seems to me that at the end of my life I would not have been haunted by Heinrich Ferstel's thought that “architectural styles cannot be invented” if the truth contained in it had not been clearly reckoned with. Yes, architectural styles cannot be invented, they must arise out of an overall spiritual life. But if such a spiritual life as a whole exists, then it may dare, even if in a modest way, even with weak forces, to also gain an art style from the same spirituality from which this spirituality itself is created. I believe that I know better than anyone else what the faults of this building are, and I can assure you that I do not think immodestly about what has been created. I know everything I would do differently if I were to build such a structure again. I know how much this building is a beginning, how much of what is intended by it in the sense of its style may have to be realized quite differently. In any case, I do not want to think immodestly about this building. But with regard to what is intended by it, it may be pointed out how it wants to prove that architectural styles cannot be invented, but that they can be born if, instead of the nihilism of world view, a spiritual positivism is set, if, instead of the decadent decline of old world views, new sources of world view are sought. This building has therefore been created with a certain inner necessity. Just as feeling led us to present our world view in the mystery plays, as if feeling were to be taken into account in addition to thinking, so should the will, which is inherent in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, first express itself artistically in this building. The fact that there is life in this spiritual science should, however, be shown in an equally modest way, just as a beginning – I always have to emphasize this – by the fact that we do not want to use this building to shut ourselves away and, as it were, strive for a higher world view as if it were a satisfaction of our inner soulful desires. No, in the next lectures on this building I will show you how all the building forms here live in such a way that they basically do not represent walls, but something artistically transparent. This is how the wall, which is designed here, differs from the walls that one is accustomed to in other architectural walls. The latter are final; one knows oneself inside a space that is limited in a certain way. Here, however, everything is shaped in such a way that, by looking at the frame, one can get the feeling, if one feels the thing in the right way, of how everything cancels itself out. Just as glass physically negates itself and becomes transparent, so the artistic forms of the walls are meant to negate themselves in order to become transparent; so painting and sculpture are meant to negate themselves in order to become transparent, so as not to lock up the soul in a room, but to lead the soul out into the world. And out of this tendency there also arose the impulse, still modest, which I call the social impulse and which in my book The Core of the Social Question should be presented to the world, not as a theory but as a call to action. Spiritual science could not remain with intellectuality. In its first phase it had to take human habits into account, had to speak to those people who were still educated entirely in abstract intellectualism. But it had to progress from thinking to feeling in order to present to the world what was to be expressed not only through the abstract word, but also through the dramatic play, the dramatic action, the dramatic image. But this spiritual science could not stop at mere feeling. It had to progress to the realm of will. It had to overcome and shape matter, it had to give form and life to matter. Therefore, a new framework, a new formal language, indeed a new architectural style, had to be sought for the mystery plays and for everything that wants to express itself through them, including the living anthroposophically oriented spiritual science itself. In order to affirm what lives as the deepest impulse in this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, the social impulse also arose quite naturally in the time when adversity taught people to replace the tendency of decline with the tendency of ascent. We wanted to gain through this building, even through its style, that state of mind through which the human being goes out to experience all of social existence, goes out to be able to participate in the necessary social reconstruction of our time with living soul content. Thus, I believe, this structure can be seen as standing within what reveals itself as the deepest needs of our time, which in turn want to lead people out of mere abstractness and the materialism associated with it, out of mere thinking and into living feeling, and into active will. And we believe that in this way we also have what must be the substance, as it were, for what is so urgently demanded of us today, for what we know: If we humans are unable to accomplish it, the slide into barbarism will continue. A worldview that encompasses the whole person, the thinking, feeling and willing human being, must also be able to provide the state of mind that enables people to work together on what is a vital necessity of the present and the near future: social action. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Double Dome Room and Its Interior Design

16 Oct 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| You know that in the case of all the buildings that are actually designed to enclose something, we are dealing with a completely different architecture. Perhaps we can reach an understanding if we point to older building forms that draw their style, their architectural concept, from completely different premises. |

| I know all the arguments that can be used against this transfer of the idea of construction from the dynamic-mathematical to the organic-living, and I understand every one of the artists who cling to the old in this direction; I feel for them. But a start had to be made sometime with what time, from its depths, demands of us humans in the present and for the near future. |

| Here it was not even ventured out of the abstract, but it was undertaken because a second, an artistic branch wanted to emerge from the same roots from which spiritual science itself emerged. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Double Dome Room and Its Interior Design

16 Oct 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

It may be clear from the two observations already made here about the building idea of Dornach how this building idea has arisen out of the same life from which that is to arise which is meant here as spiritual science. But this building idea did not arise in such a way that, in the building, what lives in thought form, in idea form, in spiritual science, is to be found again, only in outwardly symbolic pictorial form. Rather, the building was to arise out of the feelings and perceptions that can be harbored by someone who feels inspired by this spiritual science. To some extent the intention was there: on the one hand, the spiritual-scientific impulse wants to express itself in the form of ideas. But that is not enough, that does not reveal its life in a complete way, and another branch must sprout from the common root. That is precisely the artistic branch, that is what manifests itself out of feeling and perception in the building idea of Dornach. Those approaching this building from the outside will at first perceive a kind of duality: a larger dome structure as an auditorium; a smaller dome structure, which to a certain extent cuts through the larger one , as a space for performances, also conceived as the space towards which everything in the auditorium tends, and from which, in turn, everything that the auditorium is inclined to absorb should radiate. Our future development will depend on whether humanity is able to commit itself to a truly essential development in all its soul-forming aspects, to commit itself to development in such a way that one says to oneself: What one has inherited or acquired through ordinary life does not yet lead to what gives the human being a truly dignified existence. From a certain point onwards, the development of the inner life must be taken up in order to lead beyond what the outer consciousness alone can bring. But there must be something to meet what one is approaching and which one expects, as it were, from unknown depths of the spirit. And it is the feeling of this interaction between the receiving human being and the creating human being within himself that was then able to be lived out in the building idea of Dornach. From the outset, wherever domed rooms of different sizes adjoin or even intersect, one cannot help but feel that a close interaction is taking place between the person to whom the one part is dedicated and the person to whom the other part is dedicated. To a certain extent, the aim was to evoke the sensation of a rhythm that exists between the larger and the smaller component. This lively sensation, or perhaps it would be better to say this invigoration of sensation through the forms of the building, could hardly be evoked by two rooms adjacent to one another in a different way. But now that is adapted to what interior design is and from which I would like to start initially. You know that in the case of all the buildings that are actually designed to enclose something, we are dealing with a completely different architecture. Perhaps we can reach an understanding if we point to older building forms that draw their style, their architectural concept, from completely different premises. The Greek “temple is conceived as the dwelling of the god, and a Greek temple in which there is no statue of the god, of Zeus, Apollo or Athena, would not be a complete work of art. But how did this style actually come about? It arose, so to speak, from the idea of God acting from a specific point in the universe. It is intended to envelop the activity of this god; it is therefore conceived in its entirety as a covering, as an enclosure. If we go a little further, skipping other architectural styles, to the architecture of the later Middle Ages, to the Gothic cathedral, we have to say that anyone entering a Gothic cathedral cannot feel that this building is complete if it is empty. A Gothic building that is not conceived as a temple but as a cathedral, that is, as a gathering and confluence of the faithful, is only complete when the faithful are assembled in it, when they are inside, just as a Greek temple is only complete when the statue of the god is inside. Accordingly, the entire Gothic architectural style is conceived in this way. And now, penetrating into our times, one is led to say: the internalization of the human being is what must be the essential impulse of the present and the near future. Man himself, with his inwardly divine-spiritual essence, is at the center of all striving, but he kills this inner impulse of his modern striving if he does not find his way into the development in a living way. And it is from this feeling of the modern human being that the building idea here has arisen. The mere all-round principle of symmetry of Greek architecture, the enclosure, had to be dissolved, and the abstract idea of the upward striving of the crowd gathering in the cathedral also had to be dissolved. Closure had to be found, so to speak, in the upward infinity of the spherical form, development in the complete feeling for that which animates the individual form. It is perhaps partly due to external motives that part of this building is a wooden structure; it could just as easily be a concrete structure, but not, for example, a marble building. Now that it is a wooden building, I only need to speak about the peculiarity as a wooden building, which essentially presents the interior design. When working with wood as a material for architecture, for sculpture, one notices that this work in wood is something quite different from working in marble, for example, or in any material that reveals itself on the surface like marble or stone. This will be particularly apparent when the central group in the right light is seen standing in this small domed room on the east side (Fig. 92). It has become a sculptural wooden group in keeping with the overall interior design. So it was worked in wood. Of course, it was he who made a model first, since no single person can work on a nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group. I would not have been surprised if the people who saw this model, which was made in plasticine, had actually found it hideous, especially the central figure, the representative of humanity himself. For it goes without saying that the final design in wood must already have been present in the plasticine version.  But now, when working on stone – or on a surface that can resemble stone – one is obliged to carve out the form from the raised parts, from what bulges out of the plane, what confronts one from the plane; one is therefore obliged, so to speak, to place it on the plane, on the surface. When working with wood, you have to avoid working on the wood itself and instead work out of the wood. One must work not towards the convex but towards the concave. With stone and everything that resembles stone, it is that which emerges from the surface, the convex, that is effective. With everything that is made of wood, it is that which withdraws from the surface, that which is thus, as it were, cut out, hollowed out of the wood. Therefore, it is necessary – and I ask you to visualize the whole type, let us say, of the Roman Caesar heads, which can be seen everywhere in casts in museums, in relation to what I am about to say – therefore, when you sculpt the human form out of a stone-like material, you have to work the whole thing out from the face, from the head, and the rest of the human form that is not the head is actually, artistically speaking, just an appendix to the head. One must not, so to speak, sin against the natural forms of the human head, and one must shape the entire organism of the limbs and trunk out of what is laid down in the head. All this is required, for example, of marble, all this is required of stone. If one works in wood, then one has the necessity to work in the opposite sense. You have to work from the whole human figure, from the movement of the limbs, from the feeling of the torso. You can dare to shape an upward arm movement, a downward arm movement in such a way that it continues in an asymmetrical forehead, as was attempted with this group. This was only possible because it is a wood group, because when you work in wood, you bring out the hollows in the material and do not place what is raised on the surface. Only by being completely immersed in the material, with all one's feelings, especially in the human form, can such a treatment of the material emerge. And what is most vividly apparent when the human form is sculpted is apparent in the overall treatment of the wood here in this interior design. In stone, the progression of the columns from the simplest capital and pedestal forms to the more complicated middle forms, and then back to the simple forms again, would represent the dissolution of the symmetry on all sides into a developmental metamorphic progression. In stone, all of this would be nonsense; because stone demands to be more comprehensive, stone demands symmetry on all sides. Only wood allows for the development that was attempted here. As I said, it could also have been done in concrete, which, due to its nature, overcomes stone; only the form would look somewhat different. But wood allows for the introduction of development into the shape of the capital. And here I would like to say that the underlying idea was to implement Goethe's concept of metamorphosis in the purely artistic. One must, however, completely immerse oneself in the creative powers of nature and create forms out of the creative powers of nature if one dares to attempt to progress from the simplest capital forms, which you can find here at the two columns at the entrance, to ever more complicated forms. But that came about all by itself, that came about for the senses, that was not contrived. Those personalities who in earlier times were often led here in this building were told: this column means this, that column means that; they were spoken of Mercury, Mars columns and the like, and in these things, which actually only serve an abstract understanding, one has seen the main thing. The main thing is not in that. The main thing is how the second capital motif - but now for artistic perception - emerges from the first with the same necessity as the higher-lying leaf or blossom emerges from the lower-lying leaf according to the principle of natural growth, or the petal from the leaf. When forming such a concept, one looks at nature theoretically. Here it is a matter of having nothing to do with theory, but of experiencing the development as one form arises from the other. I may say: everything that you see here in the way of capitals and architraves is felt to be absolutely pure, and anyone who speculates about it, who makes symbolic interpretations about it, misunderstands the whole thing. But it is strange how, when you are working, this interweaving with the creative powers of nature brings surprises. When I was working on the model for this building (Fig. 22), I merely had the feeling that one capital would emerge from the other, that the next architrave motif would always emerge from the previous metamorphosis, and so on with the base motifs and so on. It soon became clear to me that this developmental impulse does not lead to a progression from the simpler to the more complicated, but that the most complicated is achieved right in the middle, as you can see here on the central columns, and that, in turn, when you have taken complexity to its ultimate height, to its culmination, you are compelled to move on to something simpler. Therefore, you do not see here, for example, an abstract development that starts with the simplest and progresses to the most complicated, so that the last would be the most complicated, but you see the greatest complication of the motifs in the middle.  And then I may also reveal to you here that it was certainly not intended from the outset to be a staff of Mercury entwined by snakes (Figs. 41, 42). No, that arose out of the artistic experience as something that cannot be otherwise if one ascends to the complicated in development and then has to turn around in order to descend again into the simpler. Likewise, I was surprised, for example, when – having arrived at the seventh column – I found that the sublimities of the first column, if you think of it as being turned inside out like a glove – not geometrically, but artistically turned inside out — fit exactly into the cavities of the last column; how, in turn, the same is the case with the second and sixth columns, as it is with the third and fifth columns, and the fourth column is in the middle.   It was not a case of pursuing some abstract, mystical principle of seven from the outset; rather, just as the tone scale is a seven-part entity, here the columns had to be formed in such a way that, so to speak, an octave of feeling in the form is fulfilled in a seven-part structure. For the eighth would be the octave; there it has to merge into the other kind of feeling, which one then finds in the small domed room, which contains something that accommodates development as an absorption. Therefore, the capital motifs of the small dome (Figs. 58-63) are not presented in their developed form as they are here, but are rather presented as a single entity, so to speak, opening its arms to what hastens towards it as a development.       But all this is not said beforehand, because beforehand one is dealing with something else, with life in form, with life in the plane itself. This is said afterwards, to give some indication of what has been created. Nothing here has grown out of any newer theoretical world view, not even out of the world of ideas of spiritual science itself. And I believe that it can be achieved, at least to a certain extent, that those who enter this building have the feeling: here, for the time being, one can forget everything one has absorbed in one's head in the way of spiritual-scientific ideas and thoughts. There is no need to talk about it, but one can feel it, feel it from the forms and from the treatment of the forms. So that one can feel something like this: When you enter a Greek temple, you feel the encompassing nature of this Greek temple. The stone form reigns in wisdom. From the macrocosm comes the wisdom that builds this macrocosm, pushes through the wall, as it were, and works in the stone's sublimity, in the convexities, and there encompasses the externally resting God, who is only active in the spirit for the world. One could feel in a similar way that which is striven for in a Gothic building. It is the community with its group soul, which, by being gathered in the cathedral, actually has around it that which it itself has built, bricked, chiseled, carpentered, and so on. When one enters a Gothic cathedral, one always has the feeling that, in contrast to the Greek temple, which arose from a purely aristocratic way of thinking, the Gothic cathedral is the product of a class-conscious thinking, of the structure of medieval life, which expresses itself through the search for humanity, which also expresses itself in its forms in this search for humanity. Those people who cannot bring themselves to look at it impartially speak of the Temple of Dornach. What has been built here is the opposite of any temple. There is nothing temple-like here, nothing that can be related to a church or a cathedral. And anyone who speaks of the temple of Dornach is only expressing how they have remained with Greek architecture in their whole feeling, not even having progressed to the Gothic. Here, however, what had to be tackled was that which creates forms that are basically only the continuation of what is spoken here, what is played here, what is declaimed here, what is artistically presented here. And just as the speaker stands here at the lectern, just as the organ sounds from above, just as the recitative tones vibrate through the room, so that which originates from the word, from the sound, from the thought must continue to speak through the framing, through the enclosure, which is not an enclosure but only continues the spoken, the sounded word. In the Greek temple we are dealing with an enclosure; here we are dealing with a self-expression. Therefore, above all, the whole form must be such that it lovingly embraces what is happening here, but that it does not close it off, but that this building stands as a symbol that what is being worked on here in Dornach should reach out to all of humanity. If you study the columns here, together with the back wall, which signifies enclosure, you will see that The whole can now be felt in such a way that nowhere does one have the feeling of being enclosed and speaking only to the wall; rather, one has the feeling that one is speaking and the forms of the wall, these capitals, these architraves, these column forms absorb the vibrations of the word and actually want to carry them out into the world. They do not want to close off, but want to be artistically transparent. And just as the wood here is cut in such forms that make the wood artistically permeable, so it is suggested in these windows, I would say in a more natural material way, how what is here inside should be connected with the outside. These windows are not works of art in themselves; these windows, whose technique is essentially a glass etching technique, are only works of art when sunlight shines through them, when a connection is created between what has been scratched out of the glass and the sunlight shining through. That doesn't close, that lets the sun in, that is the living mediator with the whole, with the light that floods the cosmos, and is only something if you look at it in connection with this light. If you approach it in such an artistic way, then you can also dare to develop the motifs that are in these windows. I cannot go into details, of course, but I would refer you to that blue window there (Fig. 111), where you can see the human form in both casement windows, the human form in two situations. In one case, all the qualities that live in the hunter when he aims at the animal he wants to shoot live in the person. In what has been scratched out of the glass, you will find the entire inner life of the person depicted, you will find everything that lives in him poured into the figurative. When you come to a certain stage of inner experience, you cannot help but give shape to what lives inside as passion. And if you then think of the metamorphosis as having progressed, the whole picture shows the following in the right-hand window: the person has progressed from intending to shoot the bird down to actually doing it: he has taken aim and is shooting. What happened earlier is transformed into the other part, which is then scraped out of the glass and together with the sunlight gives the work of art. In this way, each individual window could be treated. But the point here is not to come up with more interpretations, but to surrender to what is on the glass, to feel it. Precisely when one strives for the art of interpretation, one overlooks the actual artistic intention therein.  And when you look at this dome painting (Fig. 57) and see how everything that is painted in the small dome is brought out of the color, then you will also have the aspiration there to feel your way out of the closed space into the cosmos. It is painted in such a way that the painting on the surface is suspended, as if you are entering through a portal into a living thing. If you have a vivid sense of color, you can draw that out of the color. Of course, there are people who would prefer to see naturalistic figures up there; that would spare them the discomfort of first having to feel things. Because what you can feel in a beautifully—what we call “beautifully”—painted naturalistic human figure is something you have felt since childhood, and it is comfortable to see it again. But when you come here, you don't have the opportunity to rediscover what you have felt since childhood and say that it resembles this or that, but rather, here you have to, so to speak, go through all the that you have gone through in your entire life, in order to grasp in a lively way what emerges from the colors and the forms – which are, after all, the work of the color; they want to be nothing else – and to have the feeling: it does not shut you out, it carries what you feel here out into the whole world, it connects you with the world. Nothing about this building is conceived as anything other than an organic formation.  It was certainly a daring move to transfer mechanical forms of construction into the organic. If you want to develop something organic, everything has to be so that it could not be any different at the place where it occurs. Take something as insignificant as a human earlobe, which is certainly something very insignificant in the human organism. But according to the nature of the human organism, this earlobe, with its very specific shape, must form at this location here, and of course a similar organ could not develop, say, at the tip of the little finger or elsewhere. Each has its shape in its own place. This has been developed here as a building idea. Everything you see formed here (Fig. 27) has been thought out from the whole, has been thought and felt into the place where it stands. The column is dissolved in such a way that one can see the supporting function of the dissolved column in its form. If you see any motif outside at the entrance, you will see from its forms: This is towards the entrance. If you step a few steps further inside, what the column has to bear is no longer there in the same way. But if you go from the outside world into what such a column structure has to bear, the load-bearing and pushing of the whole structure against each column structure should be felt and, in turn, the relief against the outside world. What we are seeking here is an inner dynamism that strives towards life. And we live in a time when such a metamorphosis must be striven for in all fields of human endeavor, as was rightly felt in the past.  I am reminded of Schlegel, who, looking at the past forms that the “Renaissance men” repeatedly wanted to bring back, coined the beautiful phrase: “Architecture is frozen music.” It is a beautiful phrase for everything that has gone before in architecture, and an extraordinarily apt one. One has the feeling that music lives in these building thoughts. How could one see more beautifully than in the building forms of the Greek temple! How could one feel Bach, prophetically foresaw, differently than in the forms of the Gothic cathedral! The fugue already lives in the pointed arch. There it was frozen, and Friedrich Schlegel was right to call architecture, which he knew, frozen music. But today we live in a momentous moment of human development. We live in the moment when all creativity must take on a different form. And so we must also thaw and melt the frozen form of architecture. But it would dissolve into the indefinite if it were not imbued with soul in the melting process. And so we must have, alongside the frozen music, a thawing music that looks at us and demands: Give me soul! That, you see, is something of the building idea at Dornach, which spoke out of the development of humanity: thaw me, I am the frozen music! But I would melt into nothingness if, in thawing, the soul, the soul that is intensely moved within, did not lead into all forms. Not mere symmetry-proportionality should live in the forms, not merely that which one capital places in symmetry and proportionality next to the other, but living, intense movement, which allows one capital to grow out of the other like one petal of a flower out of another, metamorphosically transforming the form. I know all the arguments that can be used against this transfer of the idea of construction from the dynamic-mathematical to the organic-living, and I understand every one of the artists who cling to the old in this direction; I feel for them. But a start had to be made sometime with what time, from its depths, demands of us humans in the present and for the near future. And so only those who experience it as a need of their own soul, which has struggled to meet the demands of the present and the near future, will feel this structure. Of course, there is still a lot that is imperfect, and if it were to be performed a second time, this building would look quite different. But nevertheless, you can see from the attempt, at least, how the attempt has been made down to the smallest detail to transfer the dynamical-mathematical into the organic. Take a look at the radiators (Fig. 26). See how they are created from an organic, living elementary form, as if certain forces, which mysteriously work in the earth's interior, wanted to continue to work over the earth's surface. A few days ago, you were given a hint here as to how electricity continues to work in a mysterious way in the earth, when what is only transmitted through a wire is closed to the power circuit through the earth line, as it were, the whole earth replaces in its powers what would have to be there in a second wire line. Oh, there is much that is mysterious in the earth. But what is mysterious in the earth can be unraveled, not intellectually but intuitively. When it is shaped into forms, which should not be slavish imitations of animal or plant forms, but which are quite independent forms, then one perceives them as being alive. You can then form a wide, low stove screen and make the shape differently than if you were making a narrow, tall stove screen. You have the metamorphosing principle within you; it passes into the creative hand.  Of course, these are all things that people of the present day may still find repulsive. Let them do it. Those who cling to the old have always found what has emerged as something new repulsive. But such an experiment must be ventured some time. Here it was not even ventured out of the abstract, but it was undertaken because a second, an artistic branch wanted to emerge from the same roots from which spiritual science itself emerged. And I would like to emphasize once again: you will not find a single symbol in this room. If anything here appears to you as a symbol, it could at most be the five-petalled flower leaf at the back in the small domed room (Figs. 55 above, 57), which could appear to you as something that is meant to be symbolic when the curtain is raised later. Just as the five petals do not symbolize a pentagram, nothing here is meant to be symbolic. But everything has been so carefully thought out that every detail, every artistic line, is derived from the form of the whole.  If I have been permitted to characterize the building idea of Dornach in this way, it must be understood that I must at the same time add that what I have said is only the beginning of an attempt. And you can be sure of this: those who are working on this building, those from whom this building idea has arisen, do not think of it in an immodest way. They think about it in such a way that they would certainly retain the impulse, principle and style, the essentials, but create something completely different after they have learned what can be learned in the process of creating this building. A lot could be learned here. Because you truly do not learn more thoroughly than when you are forced to let what lives in your soul flow into concrete action. It is relatively easy to contrive abstract ideals with great perfection. But if one is compelled, already at the very first steps that an idea, an impulse inwardly takes in the soul, to shape this idea, this impulse in such a way that it can weave in the outer material, so that the work in which it embodies itself, does not become allegorical, then it requires something quite different in inner experience, then it requires a growing together with the world thought, with the world impulses, with that which lives in the world. Therefore, the Greeks, who were able not only to think about the world but also to feel it, took the word “cosmos”, with which they designated the universe, not from theory but from feeling. In the word “cosmos” lies the sense of beauty that is aroused in us when we look at the outer universe. But today, anyone who carries the thought of building in reality in their soul must be able to experience and grasp human development itself in a cosmic artistic way. We place ourselves in the sight of the portal of a Greek temple. We enter the temple. We experience the forms that surround us as a fence around the image of the god. We feel something like wisdom cast in form, that wisdom that flows through the whole world and that once had to emerge artistically in external forms, that had to be felt and that was felt in the highest way when the temple was created as the dwelling place of the Greek god. We must have a different material from the stone that allows us to shape world wisdom in its sublimity; we must have a different material when we work from the innermost being of the modern human being; for a different force must radiate out into the universe than wisdom is. We receive wisdom; it radiates towards us from what we place on the surface in terms of sublimity, of convexities. When we stand before the soft wood, we hollow into it that which lives in us, and we give something of ourselves to the cosmos. But as human beings, if we do not want to sin against the whole spirit of the world, we must carry nothing into it but what is carried into the universe on the stream of love. And anyone who can feel artistically, feels when he shapes the marble out of the flat surface, how wisdom comes over him in his consciousness when he carries out the building idea of the marble. The person who executes such a building idea as the one here feels that he must create what can be created by carving into the soft wood, what can live in the concavity, in true devotion to the greatness of the universe. One may only carve into it if one carves into it with love for the universe. No one should actually be able to form a surface with a relief without being overwhelmed by the wisdom of the universe. No one should dare to commit the sin of imprinting their own human essence on the material, of hollowing out the material, who does not do it with love for the universe. These, however, are the two poles of all human development: idea or wisdom and love. When we read Goethe's sayings in prose, it sounds to us like a fundamental solution to the riddle of the world when Goethe says: The highest that man can feel is the harmony of idea and love. We are aware that this harmony has been achieved here, for the time being only, I would almost say haltingly, in what we have now been able to do. But according to the intentions from which its idea has flowed, this structure does not want to be anything other than a germ. But a germ must not be judged only by what it initially presents itself as; a germ must be judged by what can grow out of it. These courses have been organized to help get this germ growing. And we have called you here because you are part of this building idea from Dornach. For whatever I might relate to you about the building idea of Dornach, it would all have to be unfinished, because this building idea can only be completed by those who have felt it going out into the world and - each in his own place - accomplishing that to which this building idea, with all that can be cultivated in the building, is to be the germ. I can only speak to you of something unfinished. To complete what is intended here, that cannot be done in Dornach, not by those who would work here, however fully; that can only be done effectively by you, by going out into the world and completing what can be hinted at here but must remain unfinished. You are not called upon to admire or evaluate the building, but to complete it, to be the further material in which the world spirit itself works, in which it is freely grasped by you so that in today's social distress, in today's decisive moment in world history, something may be done for the further development of humanity that leads not to barbarism but to a new, luminous ascent of human development. We would like the walls, columns, windows and domed spaces to speak to you: become the fulfillers of the architectural vision of Dornach! For it is in this sense that we have truly counted on you. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Idea of Building in Dornach

28 Feb 1921, The Hague Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The aim is not to somehow embody the ideas that are presented through images, that would be inartistic. Rather, the one spiritual life that underlies it can be shaped artistically at one time, and at another time it can be shaped ideally, in thought, scientifically. |

| This is what was attempted in Dornach. There (Fig. 64) you first see what is under the dome, the architrave motif, directly above the group that is to be placed in the east of the building as the sculptural center of this building, so to speak. |

| For this, however, it will be particularly necessary to have the international understanding that I described yesterday as the basis for a world school association that works towards the liberation of spiritual life as one member of the tripartite social organism. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Idea of Building in Dornach

28 Feb 1921, The Hague Rudolf Steiner |

|---|