| 126. Occult History: Lecture I

27 Dec 1910, Stuttgart Tr. Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Therefore when we look back to very ancient times, we-find men who were clairvoyant; we know too that this clairvoyance faded away more and more among the various peoples in the different epochs. In the Christmas lecture to-day2 I told you how in Europe, at a comparatively very late time, abundant remains of this ancient clairvoyance still survived. |

| The lecture, not yet printed in English, was entitled: Yuletide and the Christmas Symbols. Stuttgart, 27.12.1910.3. See Rudolf Steiner, World-History in the light of Anthroposophy, notably lectures III, IV, V. |

| 126. Occult History: Lecture I

27 Dec 1910, Stuttgart Tr. Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

The character of Spiritual Science is such that the truths and data of knowledge contained in it increase in difficulty the farther we descend from universal principles to concrete details. You may already have noticed this when attempts have been made in different groups to speak about historical details, for example about the reincarnations of the great leader of the ancient Persian religion, Zarathustra, or about his connection with Moses, with Hermes, and also with Jesus of Nazareth.1 On other occasions too, concrete questions of history have been touched upon. As soon as we descend from the great truths concerning the universe as pervaded and woven through by Spirit, from the great cosmic laws to the spiritual nature of a particular individuality, a particular personality, we pass from matters where the human heart will still accept, comparatively easily, this or that questionable point, into realms teeming with improbabilities. And, as a rule, those who are insufficiently prepared become incredulous when they confront this abyss between universal and specific truths. Our study is intended to be an introduction to lectures which belong to the domain of occult history and will present historical facts and personalities in the light of Spiritual Science. In these lectures I shall have many things to say to you that will seem strange. You will hear many things that will have to reckon upon the will-for-understanding promoted by all the spiritual-scientific knowledge brought before you in the course of the years. For, after all, the finest, most significant fruit of the spiritual-scientific conception of the world is that, complicated and detailed as the knowledge is, we finally have before us not a collection of dogmas, but within us, in our hearts and feelings, we possess something that carries us beyond the standpoint we can reach through any other world-view. We do not imbibe so many dogmas, tenets, or mere information, but through our knowledge we become different human beings. In a certain respect, the aspects of Spiritual Science we shall now be considering call for more than a purely intellectual understanding—for an understanding by the soul, which at many points must be willing to listen to and accept intimations that would become crass and crude if pressed into too sharp outlines. The picture I want to call up in your minds is that behind the whole evolutionary and historical process, through the millennia up to our own times, spiritual Beings, spiritual Individualities, stand as guides and leaders behind all human evolution and human happenings, and that in the greatest, most significant events in history, this or that human being appears with his whole soul, his whole being, as an instrument of spiritual Individualities standing and working with set purpose behind him. But we must familiarise ourselves with many a concept unknown in ordinary life if we are to gain insight into the strange and mysterious connections between earlier and later happenings in the course of history If you will remind yourselves of many things that have been said through the years, you will be able to picture that in ancient times—and in Post-Atlantean times, too, if we go back only a few thousand years before what is usually called the historic era—men fell into more or less abnormal states of clairvoyance. Between our matter-of-fact waking consciousness, limited as it is entirely to the physical world, and the unconscious sleeping state, there was once a realm of consciousness through which man penetrated into spiritual reality. And we know that what is nowadays explained as poetic folk-fantasy by scholars who are themselves the originators of so many scientific myths and legends, is to be traced back to ancient clairvoyance, to clairvoyant states of the human soul which in those times gazed behind physical existence and expressed what it saw in the pictures contained in myths, fairy-tales and legends. So that in old, genuinely old myths, fairy-tales and legends, more knowledge, more wisdom and truth are to be found than in the abstract erudition and science of the present day. Therefore when we look back to very ancient times, we-find men who were clairvoyant; we know too that this clairvoyance faded away more and more among the various peoples in the different epochs. In the Christmas lecture to-day2 I told you how in Europe, at a comparatively very late time, abundant remains of this ancient clairvoyance still survived. The extinguishing of clairvoyance and the advent of consciousness limited to the physical plane occur at different times among the different peoples. You can conceive that through the culture-epochs after the great Atlantean catastrophe—through the ancient Indian, ancient Persian, Egypto-Chaldean, Greco-Latin culture-epochs and an into our own—the effects produced in the plan of world-history by the activities of men have been very diverse—inevitably so, because the peoples all stood in different relationships to the spiritual world. In ancient Persian and also in ancient Egyptian times, what man inwardly felt and experienced extended upwards into the spiritual world, and spiritual Powers played into his very soul. Not until the Greco-Latin epoch did this living connection between the human soul and the spiritual world cease in essentials; nor did it disappear completely until our own times. As far as outer history is concerned, the connection exists in our time only when, with the means that are accessible to man to-day, the link between the human soul and the realities of the spiritual worlds is sought consciously. Thus in ancient times, when man looked into his own soul, this soul enshrined not only what it had learnt from the physical world, had pictured according to the pattern of the things of the physical world, but the spiritual Hierarchies ranging above man up into the spiritual worlds were experienced as immediate realities. All this worked down to the physical plane through the instrument of the human soul, and men knew themselves to be connected with these individual Beings of the higher Hierarchies. When we look back, let us say, into the Egypto-Chaldean epoch—but it must be the earlier periods of it—we find men who are, so to say, historical personalities; but we do not understand them if we think of them as historical personalities in the modern sense. When as men of the materialistic age we speak of historical personalities, we are convinced that it is only the impulses, the intentions, of the actual personalities in question that take effect in the course of history. But with this conception we can in reality understand only the men of the last three thousand years: that is—approximately of course—the men of the millennium which ended with the birth of Christ Jesus, and those of the first and the second Christian millennia in which we ourselves are living. Plato, Socrates, possibly also Thales and Pericles, are men who can still be understood as having at any rate some resemblance to ourselves. But farther back than that it is not possible to understand human beings if we attempt to do so merely by analogy with those living to-day. This applies, shall we say, to Hermes, the great Teacher of the Egyptian epoch, also to Zarathustra, and even to Moses. When we go back before the thousand. years preceding the Christian era we must reckon with the fact that wherever we have to do with historical personalities, higher Individualities, higher Hierarchies stand behind and take possession of these personalities—in the best sense of the word, of course. And now a strange phenomenon comes to light, without knowledge of which the process of historical evolution cannot really be understood. Five culture-epochs including our own, have been enumerated. Many, many thousands of years ago we come to the first Post-Atlantean culture-epoch, the ancient Indian; this was followed by the second, the ancient Persian; this by the third, the Egypto-Chaldean; this by the fourth, the Greco-Latin; and this by the fifth, our own epoch. When we go back from the Greco-Latin to the Egyptian epoch we must change our whole way of studying history: instead of looking at the purely human aspect—which it is still possible to do in connection with the figures of the Greek world as far back as the age of the Heroes—we must now apply a different criterion by looking behind the single personalities for the spiritual Powers which represent the super-personal and work through the personalities as their instruments. We must have These spiritual Individualities always in mind, so that working behind some human being an the physical plane we can discern discern a Being of the higher Hierarchies who, as it were, takes hold of him from behind and Sets him at the appropriate place in evolution. From this point of view it is highly interesting to perceive the connections between the really significant happenings—those which were determinative factors in the course of history—in the Egypto-Chaldean epoch and in the Greco-Latin epoch. These two culture-epochs follow one another, and to begin with we go back, let us say to the years from 2800 to 3200–3500 B.C.—which comparatively speaking is not so very far. Nevertheless we shall not understand happenings then—of which ancient history is already able to tell something to-day—unless behind the historical personalities we discern the higher Individualities. But then it also becomes evident to us that in the fourth, the Greco-Latin epoch, there is a kind of repetition of the really important happenings of the third epoch. It is almost as if things that in the earlier epoch an be explained through higher laws, must be explained in the following age through laws of the physical world, as if everything had sunk down, had become a stage more material, more physical. There is a kind of reflection in the physical world of great events of the preceding period. By way of introduction, I want to draw your attention to how one of the most important happenings of the Egypto-Chaldean epoch is presented to us in a significant myth, and how this event is reflected, but at a lower stage, in the Greco-Latin epoch. I shall therefore be speaking of two parallel happenings which in the occult sense belong together, the one taking place half a plane higher, as it were, and the other entirely on the physical earth but like a kind of shadow-image on the physical plane of a spiritual event of the earlier epoch. Outwardly, it is only in the form of myths that humanity has ever been able to tell of events behind which stand Beings of the higher Hierarchies. But we shall see what lies behind the myth which describes the most significant event of the Chaldean epoch.3 We will look only at the main features of this myth. There was once a great king, by name Gilgamesh. From the name itself, one who understands such matters will recognise that here we have to do not merely with a physical king, but with a divinity standing behind him, a spiritual Individuality by whom the king of Erech is inspired, who works and acts through him. Thus we have to do with one who in the real sense must be called a god-man.4 The story narrates that he oppresses the city of Erech. The city turns to its deity, Aruru, and she causes a helper to arise out of the earth. These are pictures of the myth. We shall see what deeply significant historical events lie behind it. The Goddess of the City produces Eabani out of the earth. Eabani is a kind of human being who, in comparison with Gilgamesh, seems to be of an inferior nature, for we are told that he was clothed in the skins of animals, was covered with hair, was like a wild man. Nevertheless in his wild nature there was divine Inspiration, ancient clairvoyance, clairvoyant knowledge, clairvoyant perception. Eabani comes to know a woman of Erech and is attracted by her into the City. He becomes the friend of Gilgamesh and this brings peace to the city. Gilgamesh and Eabani together are now the rulers. Then Ishtar, the Goddess of Erech, is stolen by a neighbouring city. There upon Eabani and Gilgamesh go to war with the marauding city, conquer the king and bring the Goddess back again to Erech. Gilgamesh lives near her, and here we come to the strange fact that he has no understanding of the essential nature of the Goddess. A scene takes place, directly reminiscent of a Biblical scene described in the Gospel of St. John. Gilgamesh confronts Ishtar, but his conduct is very different from that of Christ Jesus. He upbraids the Goddess for having loved many other men before she had encountered him, reproaching her particularly for her most recent attachment. Thereupon the Goddess carries her complaints to that deity, that Being of the higher Hierarchies, to whom she belongs. She goes to Anu. And now Anu sends a bull down to the earth; Gilgamesh has to engage in combat with it. Those who recall Mithras's fight with the bull will see a resemblance here. All these events—and when we come to explain the myth we shall see what depths it contains—have led meanwhile to the death of Eabani. Gilgamesh is now alone. A thought comes to him that gnaws at the very fibres of his soul. Under the impression of what he has experienced, he becomes conscious for the first time of the thought that man is mortal; a thought to which he had previously paid no heed comes before his soul in all its terror. And then he hears of the only man of earth who has remained immortal, whereas all other human beings in the Post-Atlantean epoch have become conscious of mortality: he hears of the immortal Xisuthros far away in the West. And because he is resolved to fathom the riddle of life and death, he sets out on the perilous journey to the West.5—I can tell you at once that this journey to the West is nothing else than the search for the secrets of ancient Atlantis, for happenings prior to the great Atlantean catastrophe. Gilgamesh sets out on his journey. The details are interesting. He has to pass through an entrance guarded by giant scorpions; the spirit leads him into the realm of death; he enters the kingdom of Xisuthros and there learns that in the Post-Atlantean epoch all men will inevitably be more and more penetrated with the consciousness of death. Gilgamesh now asks Xisuthros whence he has knowledge of his eternal being; how comes it that he is conscious of immortality? Thereupon Xisuthros says to him: “You too can have this consciousness, but you must undergo all that I had to experience in overcoming the terror, anxiety and loneliness through which it was my lot to pass. When the god Ea had resolved to let perish” (in what we call the Atlantean catastrophe) “that part of humanity which was to live no longer, he bade me to withdraw into a kind of ship. I was to take with me the animals that were to remain, and those Individualities who are truly to be called the Masters. By means of this ship I outlived the great catastrophe.” Xisuthros then tells Gilgamesh: “What was there undergone, you can experience only in your innermost being; but you can attain the consciousness of immortality if for seven nights and six days you refrain from sleep.” Gilgamesh wishes to submit to the test but soon falls asleep. Then the wife of Xisuthros baked seven mystic loaves which by being eaten are to be a substitute for what would have been attained in the seven nights and six days without sleep. With this “life-elixir” Gilgamesh continues his journeying, bathes as it were in a fountain of youth, and again reaches the borders of his own country in the region of the Euphrates and the Tigris. A serpent deprives him of the power of the life-elixir and so he reaches his country without it, but all the same with the consciousness that there is indeed immortality, and filled with longing to see the spirit at least, of Eabani. The spirit of Eabani appears to him, and from the discourse which then takes place we can glean how, for the culture of the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, a consciousness of the link with the spiritual world could arise.—This relationship between Gilgamesh and Eabani is very significant. I have now outlined pictures from the significant myth of Gilgamesh which, as we shall see, will lead us into the spiritual depths lying behind the Chaldean-Babylonian culture-epoch. These pictures show that two individualities stand there: the individuality of one—Gilgamesh—into whom a divine-spiritual being has penetrated; and an individuality who is more of a human being, but of such a nature that he may be called a young soul, who has had few incarnations and for that reason has carried over ancient clairvoyance into later times—Eabani. Eabani is depicted as being clothed in skins of animals. This is an indication of his wild nature; but because of this very wildness he is still endowed with ancient clairvoyance an the one hand, and an the other hand he is a young soul who has lived through far, far fewer incarnations than other souls who have reached a high level of development. Thus Gilgamesh represents a being who was ready for initiation but was not able to attain it, for the journey to the West is the journey to an initiation that was not carried through to the end. On the one side we see in Gilgamesh the actual inaugurator of the Chaldean-Babylonian culture, and working behind him a divine-spiritual Being, a kind of Fire-Spirit.6 And beside Gilgamesh there is another individuality—Eabani—a young soul who descended late to earthly incarnation. If you read the book Occult Science, you will find that the individualities returned only gradually from the planets.—The exchange of the knowledge possessed by these two is the root of the Babylonian-Chaldean culture, and we shall see that the whole of this culture is an outcome of what proceeds from Gilgamesh and Eabani. Clairvoyance from the divine man, Gilgamesh, and clairvoyance from the young soul, Eabani, penetrate into the Chaldean-Babylonian culture. This process, enacted by two beings working side by side, each of whom is necessary to the other, is then reflected in the later, fourth culture-epoch, the Greco-Latin, and in fact reflected on the physical plane. We shall of course only very gradually reach complete understanding of such a process. A more spiritual process is thus reflected on the physical plane when humanity has descended very far, when men no longer feel the relation of human personality to the divine-spiritual world. These secrets of the divine-spiritual world were preserved in the places of the Mysteries. So, for example, many of the ancient, holy secrets which proclaimed the connection of the human soul with the divine-spiritual worlds were preserved in the Mysteries of Diana of Ephesus and in the Ephesian temple. A great deal in these Mysteries was no longer comprehensible in an age when human personality had come into prominence. And like a token of how little the purely external personality understood what had remained spiritually, there stands the half-mystical figure of Herostratus, who has eyes only for the superficial aspect of personality—Herostratus who flings the burning torch into the temple of Ephesus. This deed is like a token of the clash between the personality and what had survived from ancient spirituality. And on the very same day when a man, merely in order that his name might go down to posterity, throws the burning brand into the sanctuary of Ephesus, there is born the man who has achieved more than all others for the culture of personality—and on the very soil where the culture of were personality was meant to be overcome. Herostratus flings the burning torch on the day when Alexander the Great is born—the man who is all personality! Alexander the Great stands there as the shadow-image of Gilgamesh.7 A profound truth lies behind this. In the Greco-Latin epoch, Alexander the Great stands there as the shadow image of Gilgamesh, as a projection of the spiritual on to the physical plane. And Eabani, projected on to the physical plane, is Aristotle, the teacher of Alexander the Great. Here indeed is a strange circumstance: Alexander and Aristotle standing, like Gilgamesh and Eabani, side by side. And we see how in the first third of the fourth Post-Atlantean epoch there is carried over, as it were, by Alexander the Great but transformed into the laws of the physical plane—that which had been imparted to the Babylonian-Chaldean culture by Gilgamesh. This comes to wonderful expression in the fact that, as a result of the deeds of Alexander, there was established an the scene of Egypto-Chaldean culture Alexandria itself, the city founded by Alexander in 332 B.C. in order that the great achievements of the Egypto-Babylonian-Chaldean culture-epoch might be brought together in one centre. And gradually all the streams of Post-Atlantean culture that were intended to come together did indeed converge on Alexandria, the city established an the scene of the third culture-epoch but with the character of the fourth. Alexandria outlasted the beginnings of Christianity. Indeed it was in Alexandria that the factors of greatest significance in the fourth culture-epoch developed, when Christianity was already in existence. There the great scholars were working; there the three most important streams of culture flowed together: the ancient Pagan-Grecian stream, the Christian stream and the Mosaic-Hebrew stream. They interpenetrated one another in Alexandria. And it is impossible to conceive that the culture of Alexandria which was built entirely on the foundation of personality—could have been inaugurated in any other way than through the being who was inspired by personality—Alexander the Great. For now, through the very existence of this centre of culture, everything that formerly was super-personal, extending from the human personality upwards into the spiritual world, assumed a personal character. The personalities we find in Alexandria have, as it were, everything within themselves; the Powers from higher Hierarchies who guide the personalities and set them in their allotted places, are very little in evidence. All the sages and philosophers working in Alexandria seem to be embodiments of ancient wisdom transformed into human personality; it is the personal element that speaks out of them. The singular fact is that everything in ancient Paganism that could be explained only by the teaching of how gods came down and united with daughters of men in order to bring forth heroes—all this is transformed into personal forcefulness in the men in Alexandria. And the forms which Judaism, the Mosaic culture, assumed in Alexandria can be described from what is in evidence precisely during the period when Christianity was already in existence. Nothing is to be found of those deep conceptions of a link between the world of men and the spiritual world which were present in the age of the prophets and are still to be found in the last two centuries before the beginning of our era. In Judaism too, everything has become personality. There are gifted, able men in Alexandria, men possessed of extraordinarily deep insight into the secrets of the ancient occult teachings ... but everything has become personal; personalities are working in Alexandria. And it is there that to begin with, Christianity appears, shall we say, in a distorted, debased state of infancy. Christianity, whose real function is to lead the personal element in man upwards into the impersonal, made its appearance in Alexandria in a very ruthless form. Christian personalities, in particular, acted in such a way that we often have the impression: their deeds are anticipations of later actions by bishops and archbishops working on a purely personal basis. This applies both to Archbishop Theophilus in the fourth century and to his kinsman and successor, St. Cyril.8 We can judge them only an the basis of their human failings. Christianity, which was to give to mankind the greatest of all gifts, reveals itself to begin with in its greatest failings and from its personal side. But in Alexandria a sign and token was to stand before the whole evolution of humanity. There again we have a projection on the physical plane of earlier, more spiritual conditions. In the Orphic Mysteries of ancient Greece there was a wonderful personality, one who was initiated in the Mystery-secrets and was among the most loveable, most interesting pupils of these Mysteries, well prepared by a certain Celtic occult training undergone in earlier incarnations. This individuality sought with deepest fervour for the secrets of the Orphic Mysteries. The pupils of these Mysteries had to live through in their own soul what is described in the myth of Dionysos Zagreus, who was dismembered by the Titans but whose body was carried away by Zeus into a higher life. How, as the result of a certain path taken in the Mysteries, man's life is surrendered to the outer world, how his whole being is torn in pieces so that he can no longer find his bearings within himself—this was to become an actual, individual experience in the pupils of the Orphic Mysteries. When in the ordinary way we study animals, plants and minerals, what we learn is merely abstract knowledge because we remain outside them; but anyone who wishes to obtain knowledge in the occult sense must train himself to feel as if he were actually within the animals, plants and minerals, in air and water, in springs and mountains, in stones and Stars, in other human beings—as if he were one with them. all. Nevertheless, a pupil of the Orphic Mysteries had to develop the inner strength of soul which would enable him, re-established as a self-based individuality, to triumph over the disintegration of his being in the external world. When all this had become an actual human experience, it represented in a certain sense one of the very highest secrets of Initiation. And many pupils of the Orphic Mysteries had undergone such experiences, had lived through this disintegration in the world and, as a kind of preparation for Christianity, had therewith attained the highest experience within reach in pre-Christian times. Among the pupils of the Orphic Mysteries was the loveable personality of whom I am speaking, whose earthly name has not come down to posterity, but who stands out clearly as a pupil of these Mysteries. Already in youth and then for many years, this person was closely connected with all the Greek Orphics during the period preceding that of Greek philosophy—a period of which no account is given in books an the history of philosophy. For what is recorded of Thales and Heraclitus is an echo of what the Mystery-pupils had accomplished in their way at an earlier period. And one of the pupils of the Orphic Mysteries was the individual of whom I have just spoken, whose pupil in turn was Pherecydes of Syros, referred to in the lecture-course given at Munich last year: The East in the light of the West9 Investigation of the Akasha Chronicle reveals that the individuality of that pupil of the Orphic Mysteries was reincarnated in the 4th century A.D. We find this individuality amid the activity and life of those gathered together in Alexandria, the Orphic secrets now transformed into personal experiences of the loftiest kind. It is very remarkable how all the Orphic secrets were transformed into personal experiences in this new incarnation. At the end of the 4th century, A.D., we find this individuality reborn as the daughter of a great mathematician, Theon. We see how there flashes up in her soul all that could be experienced of the Orphic Mysteries through vision of the great mathematical, light-woven texture of the universe. All this was now personal talent, personal genius. These faculties had now to be of so personal a character that it was necessary even for this individuality to have a mathematician as father in order that something might be received from heredity. Thus we look back to times when man was still in living connection with the spiritual worlds, as was this Orphic pupil; and we see the shadow-image of this pupil among those who taught in Alexandria at the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 5th century A.D. This individuality had as yet experienced nothing that enabled men at that time to see beyond the shadow-sides of Christianity at its beginning. For all that had remained in this soul as an echo of the Orphic Mysteries was still too powerful to enable any Illumination to be received from that other Light, the new Christ Event. What arose round about as Christianity, represented by men of the type of Theophilus and Cyril, was in truth of such a nature that this Orphic individuality, working now with personal faculties, had things far greater, far richer in wisdom to say and to give than those who represented Christianity in Alexandria at that time. Theophilus and Cyril were both filled with the deepest hatred of everything that was not Christian in the narrow ecclesiastical sense in which these two bishops, in particular, understood it. Christianity had assumed in them such an entirely personal character that these two patriarchs levied hirelings in their service; men were collected from far and near to form bodyguards for them. Their aim was power in its most personal sense. They were utterly obsessed by hatred of what originated in ancient times and yet was so much greater than the new that was appearing in caricatured shape. The deepest hatred was directed by the dignitaries of Christianity in Alexandria against the individuality of the reborn Orphic pupil. The fact that she was branded as a black magician will not therefore surprise us. But that was enough to incite the whole mob of hirelings against the noble, unique figure of the reborn pupil of the Orphic Mysteries. She was still young, but in spite of her youth, in spite of the fact that she was obliged to undergo much that in those days, too, imposed great hardships an a woman during a long period of study, she found her way upwards to the light that outshone all the wisdom, all the knowledge existing in those days. And it was wonderful how in the lecture halls of Hypatia—for such was the name of this reincarnated Orphic pupil—the purest, most luminous wisdom in Alexandria was presented to the enraptured listeners. She drew to her feet not only the Pagans, bat also Christians of deep and penetrating insight, such as Synesius. She was an influence of outstanding significance, and the revival of the old Pagan wisdom of Orpheus transformed into personality could be experienced in Alexandria in the figure of Hypatia. World-karma was working in the truest sense symbolically. What had constituted the secret of her Initiation was now projected, mirrored, on the physical plane. And here we come to an event that is symbolically significant in the case of many things that have taken place in historical times. We come to one of those events that is seemingly only a martyrdom, but is in reality a symbol in which spiritual forces, spiritual intimations are coming to expression. On a day in March in the year 415 A.D., Hypatia fell victim to the fury of these who formed the entourage of the patriarch of Alexandria. They resolved to rid themselves of her power, of her spiritual power. The utterly uncivilised, wild hordes were rushed in from the environs of Alexandria as well, and the chaste young sage was fetched away under false pretences. She mounted the chariot, and at a given sign the enflamed rabble fell upon her, tore off her clothing, dragged her into a church, and literally tore the flesh from her bones. The fragments of her body were then scattered around the city by these hordes, completely dehumanised by their rapacious passions. Such was the fate of the great woman philosopher, Hypatia. Symbolically, so to say, there is indicated here something that is deeply connected with the founding of Alexandria by Alexander the Great—although it happened a long time after the actual founding of the city. In this event, important secrets of the 4th Post-Atlantean epoch are reflected. This epoch, destined as it was to represent the dissolution, the sweeping-away, of the old, contained so much that was great and significant, and with paradoxical grandeur placed before the world a most pregnant symbol in the slaughter—one can call it nothing else—of Hypatia, the outstanding woman at the turn of the 4th-5th centuries of our era.

|

| 110. The Spiritual Hierarchies (1928): Lecture II

12 Apr 1909, Düsseldorf Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Let us take a man who acquires a more and more religious mood appropriate to the season as Christmas comes on, who learns to know the significance of Christmas and to know also that when the outer world of the senses is dead the life of the spirit must now grow stronger. |

| 110. The Spiritual Hierarchies (1928): Lecture II

12 Apr 1909, Düsseldorf Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

[ 1 ] The teaching which came from the holy Rishis, during the first post-Atlantean period of civilisation was a knowledge that sprang from purely spiritual sources of existence. What is so important in that teaching and in the investigations of those times is that it entered so deeply into the processes of nature and realised so well the activity of the spirit in those processes. In reality we are always surrounded by spiritual activities and by spiritual entities. When during the time of that ancient holy teaching, mention was made of the phenomena of the world surrounding us, one was always referred to as being the most significant, the most important of all these, this was considered (by that ancient spiritual science) to be the phenomenon of fire. In all explanations of what exists and happens upon the earth, the central point of importance was always given to the spiritual investigation of fire. If we want to understand what we may call the Eastern teaching about fire, which was of such far-reaching importance in those ancient times for the acquisition of the knowledge and understanding of all life, then we must look around us at the other phenomena and occurrences of nature and see how these were considered by that very ancient teaching, which can still be useful nowadays for the purposes of spiritual science. [ 2 ] All that surrounds man in the world was then referred back to the so-called four elements. These four elements are respected no longer by the materialistic science of to-day. You all know that these four elements are called Earth, Water, Air, Fire. But where spiritual science flourished the word ‘earth’ had not the same meaning as it has nowadays. It stood for a certain state in the material realm: the state or condition of solidity. All that is solid was called ‘earthy’ by the spiritual science of those times. So whether we take the solid earth of a field, or a piece of crystal, or lead, or gold, anything that is solid was then called earth. Everything liquid, not only the water of to-day, was characterised as watery, or as water. If for instance you take iron, pass it through heat to the point of melting so that it can flow, then that liquid iron would have been called water by spiritual science. All metals when liquid were described as water. Everything that has the character of air for us to day, no matter whether it was the condition we call gas, or oxygen, or hydrogen, or other gases, was called air. [ 3 ] Fire was considered the fourth element. Those of you who remember elementary physics will know that modern science does not see in fire anything that could be compared with either earth, water or air: the physical science of to day sees in it only a certain condition of movement. Spiritual science sees in warmth or fire something which has in it a still finer substance than air. Just as earth or solidity changes into liquid, So does all air-substance change gradually into the condition of fire — according to spiritual science — and fire is so fine an element that it interpenetrates all other elements. Fire interpenetrates the air and makes it warm, the same with water and earth. The other three elements are, so to speak, separated from each other, but we see the element of fire interpenetrating them all. [ 4 ] Both ancient and modern spiritual science agree that there is yet another still more remarkable difference between what we call Earth, Water, Air, and what we call Fire or Warmth. How do we come to the cognisance of earth or solidity? Through touching it. We realise the solid through touching it and feeling its resistance. It is the same with watery substance. This gives way, it is not so resistant, still we realize it as something external that offers resistance. And it is the same with the element of air. We recognise it also as something external. With warmth it is different. Here we find something which modern science does not consider important, but which must become important for us if we want to study the real problems of existence. We can realise warmth without coming in contact with it externally. What is essential is that we can realise warmth by touching a body which has a certain degree of warmth: we can perceive it externally in the same way as we realise the three other elements, but we also feel it in our inward conditions. Therefore ancient science says (and did so already at the time of the old Indians), that earth, water, air, can be realised only in the outer world, but warmth is the first element which can also be felt within oneself. Thus, fire or warmth has, so to speak, two sides to it. An outer, which it shows when we take cognisance of it in the outer world and an inner when we feel that we ourselves are in a certain state of warmth. Man feels his own condition of warmth; he is hot, or he freezes; but consciously he is not much concerned with the gaseous or liquid or solid substances — the air, water, or earth — which are in him. He begins to ‘feel’ himself in the element of warmth. The element of warmth has an inner and an outward side. Therefore both ancient and modern spiritual science agree that warmth or fire is that wherein matter begins to become soul. And so in the true sense of the word — we may speak of an outer fire which we realise in the other elements, and of an inner psychic fire within our soul. [ 5 ] In this way, spiritual science always considered fire as the link between the outer material world on the one side, and the realm of the soul on the other, which can be known by man within his inner being. Fire or warmth was placed in the centre of all observations of nature, because fire is, so to speak, the portal through which we may pass from the outer into the inner. In all truth, fire is like a door in front of which one stands. One sees it from outside, one opens it and can observe it from within. Such is fire amongst the objects of nature. One touches some object and becomes acquainted with fire, which streams towards us from outside like the three other elements: one realises one's own inner warmth and feels it as something belonging to oneself; one stands inside the portal, one has entered into the realm of the soul. Thus was the science of fire described. In fire was seen the interplay of soul and matter. We have now placed before our souls an elementary lesson of primeval human wisdom. [ 6 ] The ancient teachers may have spoken thus: ‘Look at that burning object. See how the fire destroys it. Thou seest two things in that burning object.’ In those ancient times one was called smoke, and it may still be so called nowadays, and the other was called light, and the spiritual scientist saw the fire in the middle between light and smoke. The teacher said: ‘Out of the flame are born simultaneously light on the one side, smoke on the other.’ [ 7 ] Now we must for once put very clearly before us a very simple but very far-reaching fact, which has to do with the light, which is born of fire. It is most probable that many people when asked whether they see the light would answer: ‘Yes, of course.’ And yet this answer is as false as possible; for, in truth, no physical eye can see light. Through light one sees objects which are solid, liquid, or gaseous, but the light itself one does not see. Imagine the whole of universal space illuminated by a light the source of which was somewhere behind you, where you could not see it and you were to look into the world spaces illuminated through and through by that light. Would you see the light? You would see absolutely nothing. You would first see something when some object was placed within that illuminated space. One does not see the light, one sees the solid, the watery, the gaseous, by means of the light. One does not see physical light with the physical eye. This is something which comes before the spiritual eye with particular clearness. Spiritual science says therefore: light makes everything visible, but is itself invisible. This sentence is important: light is imperceptible. It cannot be perceived by the outer senses: one call perceive what is solid, liquid, or gaseous, finally one can perceive warmth or fire outwardly. This one can also begin to feel inwardly, but light itself one can no longer perceive outwardly. If you believe that when you see the sun you see light you are mistaken: you see a flaming body, a burning substance out of which the light streams. It could be proved to you that you have there gaseous, liquid, and earthy substances. You do not see light, you see that which is burning. [ 8 ] But spiritual science says we pass in ascending order from earth to water, from air to fire, and then to light, we pass thus from the outwardly recognisable world, from the visible world into the invisible, into the etheric-spiritual world. Fire stands on the border between the outwardly visible, material world, and that which is etheric and spiritual, which is no more outwardly visible or recognisable. What happens to a body that is destroyed through fire? What happens when something burns? When something burns, we see on one side light appear, which is outwardly imperceptible and which is operative in the spiritual world. Something that is not merely outer material gives forth the warmth and when it is strong enough to become a source of light it yields something invisible, something which cannot be recognised any more through the outer senses, but it must pay for this in smoke. From what was formerly translucent and transparent it has to bring forth something not transparent — something of the nature of smoke. Thus you see how warmth or fire becomes differentiated, how it divides. On one side it divides itself into light, with which it opens a way into the super-sensible world, and in payment for that which it sends up as light into the super-sensible world, it must send something down into the material world, into the world of non-transparent, visible things. Nothing one-sided comes forth in the world. Everything that exists has two sides to it. When light is produced through warmth, then turbid, dark matter appears on the other side. That is the teaching of primeval spiritual science. [ 9 ] But the process we have just described is only the outer side, the physical, material process. At the foundation of this physically material process there lies something essentially different. When you have only warmth in some object which as yet does not shine, then this warmth which you perceive is itself the outer physical part but within it is something spiritual. When this warmth grows so strong that it begins to shine and smoke is formed, then some of the spirit which was in the warmth must go into the smoke. That spiritual part which was in the warmth and has passed into the smoke, which being gaseous and belonging to air is a lower element than warmth, that spiritual part is transmuted, bewitched, as it were, into smoke. Thus with everything which like a turbid extract or a materialisation is deposited by the warmth, there is also associated what might be called the bewitching of some spiritual being. We can explain it still more simply. Let us imagine that we reduce air to a watery condition. Air itself is nothing but solidified warmth, densified warmth in which smoke has been formed. The spiritual part which really wanted to be in the fire has been bewitched into smoke. Spiritual beings, which are also called elementals, are bewitched in all air, and will even be bewitched, banished, so to speak, to a lower existence, when air is changed into water. Hence spiritual science sees in everything that is outwardly perceptible something that has proceeded from an original condition of fire or warmth and which has turned into air, smoke, or gas, when the warmth began to condense into gas, gas into liquid, liquid into solid. ‘Look backwards,’ says the spiritual scientist, look at any solid substance. That solidity was once liquid, it is only in the course of evolution that it has become solid and the liquid was once upon a time gaseous and the gaseous formed itself as smoke, out of the fire. But a transmutation, a bewitching of spiritual being is always connected with these processes of condensation and with the formation of gases and solids. [ 10 ] Let us now look around at our world: we see solid rocks, flowing streams of water, we see the water changing into rising mist: we see the air, we see all the solid, liquid, gaseous things and we see fire, so that at the foundation of all things we have nothing but fire. All is fire — solidified fire: gold, silver, copper, are solidified fire. All things were once upon a time fire; everything has been born out of fire. But in all that solidified realm, some bewitched spirits are dwelling. [ 11 ] How are those spiritual, divine beings who surround us able to produce solid matter as it is on our planet — to produce liquids, and air substances? They send down their elemental spirits, those which live in the fire: they imprison them in air, in water and in earth. These are the emissaries, the elemental emissaries of the spiritual, creative, building beings. The elemental spirits first enter into fire. In fire they still feel comfortable — if we care to express it by images — and then they are condemned to a life of bewitchment. We can say looking around us: ‘These beings, whom we have to thank for all the things that surround us, had to come down out of the fire-element; they are bewitched in those things.’ [ 12 ] Can we as men do anything to help those elemental spirits? This is the great question which was put by the Holy Rishis. Can we do anything to release, to redeem, all that is here, bewitched? Yes! We can help them. Because what we men do here in the physical world is nothing else than an outward expression of spiritual processes. All we do is also of importance for the spiritual world. Let us consider the following. A man stands in front of a crystal, or a lump of gold, or anything of that kind. He looks at it. What happens when a man simply gazes, simply stares with his physical eye upon some outer object? A continual interplay occurs between the man and the bewitched elemental spirits. The man and that which is bewitched in the substance have something to do with each other. Let us suppose that the man only stares at the object and takes in only what is impressed on his physical eye. Something is always passing from the elemental being into the man. Something from those bewitched elementals passes continually into the man, from morning till night. While you are thus regarding objects, hosts of these elemental beings, who were and are being continually bewitched through the world-processes of condensation, are continually entering from your surroundings into you. Let us take it that the man staring at the objects has no inclination whatever to think about those objects, no inclination to let the spirit of things live in his soul. He lives comfortably, merely passes through the world, but he does not work on it spiritually, with his ideas or feelings or in any such way. He remains simply a spectator of the material things he meets with in the world. Then these elemental spirits pass into him and remain there, having gained nothing from the world's process, but the fact of having passed from the outer world into man. Let us take another kind of man, one who works spiritually on the impressions he receives from the outer world, who with his understanding and ideas forms conceptions regarding the spiritual foundations of the world, one who does not simply stare at a metal, but ponders over its nature and feels the beauty which inspires and spiritualises his impressions. What does such a man do? Through his own spiritual process, he releases the elemental being which has streamed into him from the outer world; he raises it to what it was before, he frees the elemental from its state of enchantment. Thus, through our own spiritual life, we can, without changing them, either imprison within us those spirits which are bewitched in air, water and earth, or else through our own increasing spirituality, free them and lead them back to their own element. During the whole of his earthly life, man lets those elemental spirits stream into him from the outer world. In the same measure in which he only stares at things, in the same measure in which he simply lets the spirit dwell in him without transforming them, so, in like measure as he tries with his ideas, conceptions and feeling for beauty to work out spiritually what he sees in the outer world, does he release and redeem those spiritual elemental beings. [ 13 ] Now what happens to those elemental beings which, having come out of things, enter into man? They remain at first within him. Also those which are released at first remain, but they stay only until his death. When the man passes through death a differentiation takes place between those elemental beings which have simply passed into him and which he had not led back to their higher element, and those whom he has through his own spiritualisation led back to their former condition. Those whom the man has not changed have not gained anything from their passage from the outer world into him, but others have gained the possibility of returning to their own original world with the man's death. During his life man is a place of transition for these elemental beings. When he has passed through the spiritual world and returns to earth in his next incarnation, all the elemental beings which he has not released during his former life flock into him again when he passes through the portals of his new birth, they return with him into the physical world; but those he has released he does not bring back with him for they have returned into their original element. [ 14 ] Thus we see how man has it in his power, by the way he acts and feels towards outer nature, either to release those elemental spirits which have been necessarily bewitched through the coming into existence of our earth, or to bind them to the earth still more strongly than they were before. What does a man do when, in looking at some outer object he releases from it an elemental being by elucidating it? He spiritually does the opposite of what has been done before. Previously, smoke had been brought forth out of fire, but man spiritually forms fire again out of that smoke; only after death does he release this fire. Now think for a moment of the endless depth and spirituality of the ancient ceremonies of sacrifice, as seen in the light of primeval spiritual science! Imagine to yourselves the Priest at the sacrificial altar in those times when religion was built on the real knowledge of spiritual laws; think of the Priest lighting the flame, and the rising of the smoke, and as the smoke rises a real sacrifice is offered, for it is followed upwards by prayers — What happens then? What happens during such a sacrifice? The Priest stands at the altar where the smoke is produced. Where something solid comes out of the warmth, a spirit is being transmuted, bewitched. But because the man follows the whole procedure with prayers, he at the same time receives that spirit into himself in such a way that after death it rises again into the higher world. What did the teacher of ancient wisdom say to those who had to understand this? He said: ‘If thou lookest upon the outer world in such a way that thy spiritual process does not stop at the smoke, but rises to the element of fire, then after thy death thou dost free the spirit which is bewitched in the smoke.’ Yes! The teacher who knew the fate of the spirit, which after being bewitched in the smoke had passed into man, spoke thus: ‘If thou leavest that spirit as it was when it was in the smoke, then it must be reborn with thee and cannot rise into the spiritual world after thy death; but if thou hast released it and restored it to the fire, then after thy death it will rise again into the spiritual worlds and will not need to return to the earth at thy rebirth.’ [ 15 ] Now we have explained one part of that profound sentence from the Bhagavad Gita of which I spoke in my last lecture. It does not speak here at all of the human Ego, it speaks of those nature spirits, of these elemental beings which enter into man from the outer world, and it says there: ‘Behold the fire, behold the smoke, that which man through his spiritual processes turns into fire are spirits which he liberates with his death.’ That which he leaves as it is, in the smoke, must remain united to him at his death and must be reborn with him when he returns to earth. It is the destiny of the elemental spirits that is here described; through the wisdom which man develops, he continually liberates at his death these elemental spirits; through lack of wisdom, through the materialistic attachment to the mere things of the senses, he ties those elemental spirits to himself and forces them to follow him into this world, ever to be born again with him. [ 16 ] But these elemental beings are not only associated with fire and with what is connected with fire, they are the emissaries of higher spiritual divine beings in all that takes place in the outer sense world. There never could have been that interplay of forces in the world that produce the day and the night, for instance, if numbers of such elemental being had not worked suitably at the rotation of the planet through the universe, so that precisely this interchange of day and night could come about. All that takes place is the result of the activity of hosts of lower and higher spiritual entities belonging to the spiritual hierarchies. We have been speaking of the lowest order, of the messengers. When night becomes day and day night, elemental beings live also in that process, and so it is that man stands in an intimate relationship with the beings of the elemental world which have to take part in working at the day and the night. When man is idle and lets himself go, he affects those elementals who have to do with the day and the night quite differently, than when he has creative force, when he is active, diligent, and productive. When a man is lazy for instance, he unites himself with a certain kind of elemental and he also does so when he is active, but in a particular way. Those elementals of the second class, just named, who are active during the day, are then in their higher element. As fire elementals, those of the first class, are bound in air water and earth, so certain elemental being are also tied to darkness; and day could not turn into night, day could not be divided from night, if these elementals were not so to speak imprisoned in night. That man is able to enjoy daylight, he has to thank divine spiritual beings who have driven forth elemental spirits and have chained them to the night-time. When man is lazy these elementals flow into him continually, but he leaves them as they are, unchanged. Those elemental spirits which at night are chained to darkness, he let through his idleness remain in the same state; those elemental who enter into him when he is active and industrious and filled with working power, he leads back into daylight. Thus he continually releases these elementals of the second class. Throughout the whole of our lifetime we bear within us all those elemental spirits which have entered into us either during our hours of idleness or during those of active work. When we pass through the gates of death those beings whom we have led towards daylight can now return into the spirit world; those we have left chained to the night through our idleness, must return with us in our new incarnation. With this we arrive at the second point in the Bhagavad Gita. Again it is not the human self, but those elemental beings which are indicated with the words: ‘Behold the day and the night. That which thou hast thyself released by turning it from a being of the night into a being of the day through thy diligence; that which comes forth out of the day enters when thou diest, into the higher world; that which thou takest with thee as beings of the night, thou forcest to reincarnate with thee again.’ [ 17 ] And now you will see clearly how the matter proceeds. As it is with the phenomena of which we have just spoken, so it is on a larger scale with our month of 28 days, with the changes of the waxing and waning moon. Whole flocks of elemental beings have to come into activity to direct the motions of the moon so that our lunar periods can come about as they do with all the influences they bring with them upon our visible earth. For this purpose certain of the higher beings had again to be bewitched, doomed, chained. Clairvoyant vision sees how, with the waxing moon, spiritual beings of a lower kingdom ever rise into a higher. But, so that order should exist, other spiritual elemental beings must again be transformed into those of lower realms. There are also those elementals of a third realm who stand in relationship with men. When man is serene and bright, when he is pleased with the world, when he has feelings of gladness towards all things, he continually releases those beings which are chained to the waning moon. These beings enter into him and are continually set free, through his soul's peaceful attitude, through his inner contentment, through his harmonious feelings and ideas towards the whole world. The beings which enter into man when he is sullen, peevish, morose, discontented with anything, when everything depresses him — when he is pessimistic — these spirits remain in the condition of bewitchment they were in at the time of the waning moon. Oh! There are men who through the harmonious condition of their soul, through the bright way they look upon the world, release and set free great numbers of these bewitched elemental beings. The man of harmonious and optimistic feelings and who feels inner satisfaction with the world, is a deliverer of elemental spiritual beings. The pessimist, he who is morose, sullen and discontented, becomes through his depression the gaoler of elemental spirits which could have been released by his cheerfulness. Thus you see that the conditions of mind and soul have not only a personal importance for this man, but also that he works either at the liberation or the imprisonment of spiritual beings; either deliverance or fetters proceed from him. The conditions of soul that a man experiences go out in all directions into the spiritual world. We have here the third point of that important teaching in the Bhagavad Gita: ‘Behold what man does through the feelings and conditions of his soul, how he sets spirits free, as they are set free by the growing moon.’ When the man dies, these released spirits can return to the spiritual world. If through his depression and hypochondriacal moods, he calls to him the elemental spirits which are around him, and then leaves them as they are, as they have to be in order to bring about the orderly courses of the moon, then these spirits remain chained to him and must reincarnate with him into this world. [ 18 ] And last of all we have a fourth degree of elemental spirits, those who have to work at the annual course of the sun, so that the summer sun may shine upon the earth to awaken and fructify it, so that spring can appear and be succeeded by autumn. In order that this may come to pass certain spirits must be fettered to winter-time, must be bewitched during the time of the winter sun. And man acts upon these spirits in the same way as we have described his acting on the other grades of spirits. Let us take man who at the beginning of winter says to himself: ‘The nights are getting longer, the days shorter, we come to that time of the sun's yearly course when the sun withdraws his fructifying forces from the earth. The outer earth dies, but with this deadening of the earth I feel it my duty to be all the more spiritually awake. I must now take more and more of the spirit within me.’ Let us take a man who acquires a more and more religious mood appropriate to the season as Christmas comes on, who learns to know the significance of Christmas and to know also that when the outer world of the senses is dead the life of the spirit must now grow stronger. This man lives through winter until Easter. He remembers that with the awakening of the outer world is combined the death of the spiritual: he lives through the Easter festival comprehending its meaning. Such a man has not only an outer religion; he has religious understanding of the processes of nature, of the spirit which rules it; and through his piety, his spirituality, he releases numbers of that fourth class of elemental beings which continually stream in and out of him, which are connected with the course of the sun. But the man who is not pious in this sense, who denies or does not understand the spirit and is always muddling through a materialistic chaos, into him these elementals of the fourth class flow, but remain unchanged. At death it happens again: that these elemental spirits of the fourth degree are either set free in their own element, or else are bound to the man and have to return with him at his next incarnation. Thus, the man, who uniting with the winter spirits does not change them into summer spirits, does not redeem them through his spirituality, dooms them to rebirth, whereas they might have been freed and not have had to return with him. [ 19 ] Behold the fire and the smoke! If you so unite with the outer world that the activity of your soul and spirit is like that of fire, from which smoke comes forth, so that you spiritualise things, through knowledge and through right feeling, you help certain spiritual elemental beings to rise; but if you unite with the smoke you condemn them to rebirth. If you associate yourself with the day, you then set free the corresponding spirits of day and so on. Behold the light! Behold the day! Behold the waxing of the moon and the sunny half of the year! If you act so that you lead the elemental spirits back to the light, to the day, to the waxing moon, to the summer-time of the year, you then at your death release these elementary spirits which are so necessary to you. They rise to the spiritual world. If you associate yourself with the smoke, if you only gaze at the solid things of the earth, if through laziness you unite yourself with the night and with the spirits of the waning moon, and if through your depression you unite yourself with those spirits who are chained to the winter sun, then through your lack of spirit, your godlessness, you condemn these elementary beings to be reincarnated with you again! [ 20 ] Now we know for the first time what this passage in the Bhagavad Gita really means. If anyone thinks that man is here spoken of, he does not understand the Bhagavad Gita; but those who know that all human life is a continual interplay between man and the spirits who live bewitched into our surroundings and who must be released again — those know that these sentences speak of the ascension or of the reincarnation of four groups of elemental beings. The mystery of this lowest kind of hierarchy has been preserved for us in these sentences in the Bhagavad Gita. Yes! When one has to bring forth out of primeval wisdom what is presented to us in the documents of ancient religion, one sees how grand these are and how wrong it is to understand them superficially and not in all their profundity. They are only considered in the right way when one says to oneself: ‘No wisdom is exalted enough to discover the mysteries herein contained.’ Only when these ancient documents are interpenetrated by the magic of real devotional feeling, do they become what in the true sense of the word they must be — self-ennobling and purifying forces for human evolution. They point frequently to fathomless abysses of human wisdom, and only when that which springs from the sources of the occult schools and the mysteries, streams forth from now on to all mankind, only then, will these reflections of the primeval wisdom (for they are but reflections) be seen in all their greatness. [ 21 ] We have had to show, by means of a comparatively difficult example, how in the times of primeval wisdom the co-operation of all those spirits which are everywhere around us was well known, how it was also known that the deeds of men represent an interchanging activity between the spiritual world and the world of man's own inner being. The problem of humanity first becomes important for us, when we know that in all we do, even in our moods, we influence a whole Cosmos, and that this small world of ours is of infinitely far-reaching importance for all that comes to pass in the macrocosm. An increase in our feeling of responsibility is the finest and most important of all the things we gain from spiritual science. It teaches us to grasp the true meaning of life and to realise its importance, so that this life which we cast on the stream of evolution may not enter that stream void of meaning. |

| 110. Community Life, Inner Development, Sexuality and the Spiritual Teacher: The Protagonists

|

|---|

| Rudolf Steiner's marriage to Marie von Sivers at Christmas of 1914 had provoked not only general gossip, but also some bizarre mystical behavior on the part of a member named Alice Sprengel. [ Note 1 ] Heinrich Goesch (see below) and his wife Gertrud seized upon her strange ideas and made use of them in personal attacks on Rudolf Steiner. |

| In addition, having been asked to play Theodora gave rise to the delusion that she had received a symbolic promise of marriage from Rudolf Steiner, and she then suffered a breakdown as a result of Rudolf Steiner's marriage to Marie von Sivers at Christmas 1914. Her letters to Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner, reproduced below, clearly reveal that she was deeply upset. |

| 110. Community Life, Inner Development, Sexuality and the Spiritual Teacher: The Protagonists

|

|---|

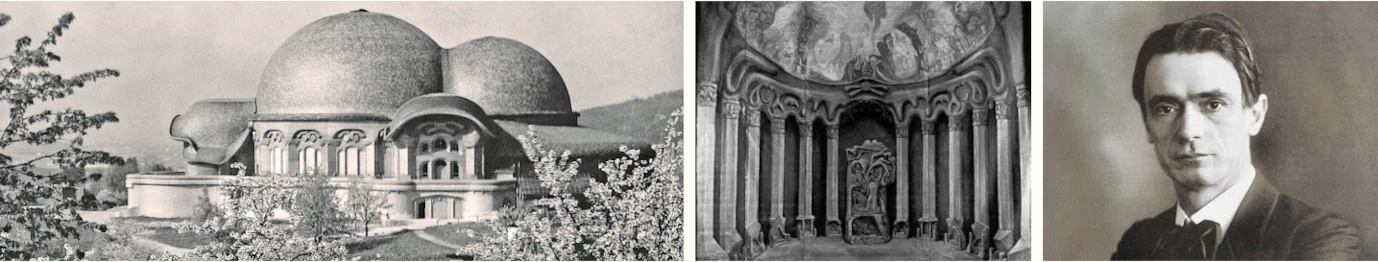

IN 1913 on the hill in Dornach near Basel, Switzerland, construction had begun on the building then known as the Johannesbau and later to be called the Goetheanum, the central headquarters of the anthroposophical movement. Members of the Anthroposophical Society from all parts of the world had been called upon to work on the building, and they were joined by a growing number of others who moved to Dornach, either permanently or temporarily, on their own initiative. Thus a unique center of anthroposophical activity developed in Dornach, a center that was, understandably enough, burdened with the shortcomings and problems unavoidable in such a group. In the summer of 1914, these difficulties escalated when World War I broke out, since people from many different nations, including those at war, had to work together and get along with each other. Isolation from the rest of the world and, last but not least, both local and more widespread opposition to the building and the people it attracted, further complicated the situation. In spite of all obstacles, however, the building continued to grow under the artistic leadership of Rudolf Steiner, who was well-loved as a teacher and felt by all to be a bulwark of constancy. But in the summer of 1915 all this changed as a result of incidents that threatened to test the Dornach group, and thus the Anthroposophical Society as a whole, to the breaking point. Rudolf Steiner's marriage to Marie von Sivers at Christmas of 1914 had provoked not only general gossip, but also some bizarre mystical behavior on the part of a member named Alice Sprengel. [ Note 1 ] Heinrich Goesch (see below) and his wife Gertrud seized upon her strange ideas and made use of them in personal attacks on Rudolf Steiner. Since this was done publicly in the context of the Society, Rudolf Steiner asked that the Society itself resolve the case. This resulted in weeks of debate, at the end of which all three were expelled from the Society. Rudolf and Marie Steiner did not take part either in the debates or in the decision to rescind their membership. The documents that follow reconstruct the events of the case in the sequence in which they occurred. Alice Sprengel (b. 1871 in Scotland, d. 1949 in Bern, Switzerland) had joined the Theosophical Society in Munich in the summer of 1902, at a time when Rudolf Steiner had not yet become General Secretary for Germany. She joined the German Section a few years later. In a notice issued by the Vorstand of the Anthroposophical Society in the fall of 1915 informing members about the case, Miss Sprengel is described as having undergone unusual suffering in her childhood. At the time of her entry into the Society, she still impressed people as being very dejected. In addition, she was unemployed at that time and outwardly in very unfortunate circumstances. For that reason, efforts were made to help her. Marie Steiner, then Marie von Sivers, sponsored her involvement in the Munich drama festival in 1907 and arranged for her to be financially supported by members in Munich. In order to help her find a means of supporting herself in line with her artistic abilities, Rudolf Steiner advised her on making symbolic jewelry and the like for members of the Society. It was also made possible for her to make the move to Dornach in 1914. She, however, interpreted this generous assistance to mean that she had a significant mission to fulfill within the Society. Having been given the role of Theodora in Rudolf Steiner's mystery dramas fed her delusions with regard to her mission, as did the fact that toward the end of the year 1911, in conjunction with the project to construct a building to house the mystery dramas, Rudolf Steiner had made an attempt to found a “Society for Theosophical Art and Style” in which she had been nominated as “keeper of the seal” because of her work as an artist. She imagined having lived through important incarnations and even believed herself to be the inspirer of Rudolf Steiner's spiritual teachings. In addition, having been asked to play Theodora gave rise to the delusion that she had received a symbolic promise of marriage from Rudolf Steiner, and she then suffered a breakdown as a result of Rudolf Steiner's marriage to Marie von Sivers at Christmas 1914. Her letters to Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner, reproduced below, clearly reveal that she was deeply upset. Letter from Alice Sprengel to Rudolf Steiner “Seven years now have passed,” [ Note 2 ] Dr. Steiner, since you appeared to my inner vision and said to me, “I am the one you have spent your life waiting for; I am the one for whom the powers of destiny intended you.” You saw the struggles and doubts this experience occasioned in me; you knew that in the end my conviction was unshakable—yes, so it is. And you waited for my soul to open and for me to speak about this. Yet I remained silent, because my heart was broken. Long before I learned of theosophy, but also much more recently, I had had many experiences that made me say, “I willingly accept whatever suffering life brings me, no matter how hard it may be. After all, I have been shown by the spirit that it cannot be different.” But this is something that seems to go beyond the original plan of destiny; I lack the strength to bear it, and so it kills something in me, destroys forces I should once have possessed. These experiences were mostly instances of people deliberately abusing my confidence, and all in the name of love. But I had the feeling that this was not only my own fault; it seemed as if the will of destiny was inflicting more on me than I could bear. I had some vague idea of why that might be so. Once, some years ago, I heard a voice within me saying, “There are beings in the spiritual world whose work requires that human beings sustain hope, but they have no interest in seeing these hopes fulfilled—on the contrary.” At that point I was not fully aware of what we were later to hear about the mystery of premature death, of goals not achieved, and so forth. Then, however, I bore within me a wish and a hope that seemed like a proclamation from the spiritual world. This wish and this hope had made it possible for me to bear the unbearable; they worked in me with such tremendous force that they carried me along with them. My soul was in such a condition, however, that it could neither relinquish them nor tolerate their fulfillment, or, to put it better, it could not live up to what their fulfillment would have demanded of it. Thus I could not come to clarity on what the above-mentioned experience meant for me as an earthly human being. Neither the teaching nor the teacher was enough to revive my soul; that could only be done by a human being capable of greater love than any other and thus capable of compensating for a greater lack of love. I can no longer remain silent; it speaks in me and forces me to speak. Years ago I begged you for advice, asked for enlightenment, and your words gave me hope and comfort. I am grateful for that, but today I would no longer be able to bear it. Why did you say to me recently that I looked well, that I should persevere? Did you think I was already aware of the step you are taking now, and that I had already “gotten over it”? I was as far from that as ever. In conclusion, I ask that you let Miss von Sivers read this letter.