Foundation Course

Spiritual Discernment, Religious Feeling, Sacramental Action

GA 343

3 October 1921 a.m., Dornach

XIV. Gnostics and Montanists

[ 1 ] My dear friends! Yesterday we started by addressing a wish which licentiate Bock had expressed at the beginning of our course and we find that what we need to build on to what I said yesterday afternoon about sacramentalism relevant to today, can be discovered if we link the possible reflections, which are necessary, to the 13th chapter of the Gospel of St Mark. It is important for us to certainly try again, in all seriousness, to derive specific meaning from what is expressed in living words. To me it is impossible that pastoral care can be developed in the future, without yourself developing the application of living words and even experiencing living words. However, it is impossible for current mankind which is so strongly gripped by materialism, to be able to handle the living Word in itself, without a historical deepening. It is simply so, that in dealing with intellectualistic concepts and ideas we are only dealing with dead words, with the corpse of the Logos. We will only deal with the living Word when we penetrate through the layer in which man lives today, only, and alone, by penetrating through the layer of the dead, the corpse-like words.

[ 2 ] My dear friends, the Catholic Church has to a certain degree understood very well how to misplace and obstruct access to these living words for those who, in their opinion, should be the true believers. In pastoral care the Catholic Church in a certain sense considers these enlivening words already, but in an outward sense. All these things will only become understood when we take what I presented yesterday and think them through deeply, and, if we can still penetrate them further, to yield clarity. I'm saying that the Catholic Church understood very clearly in this regard, to exterminate the life of the Word, because it belonged to one of the most significant epochs of all human development, and which had contributed briefly before and some three centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha, just to the civilized part of humanity.

[ 3 ] When we ask our contemporaries about the essence of the Gnosis, for example the essence of the Montanistic heresy, then with the current soul constitution you basically can't understand anything correctly relating to it. That which would outwardly be informative in the becoming church has been carefully eradicated and the things that archaeologists, philosophers, researchers of antiquity discover from this characterised epoch, will indeed be deciphered word for word, but the decipherment does not mean reaching an understanding. All of this must actually be read differently, in order to enter the real soul content of olden times. It is for instance possible for modern humanity, to take the Deussen translation, which has exterminated all real meaning of the Orient, and, while thinking these translations are great, while mankind can't eradicate all understanding for what Deussen translated, devote yourself to such a Deussen translation. In order to understand, you need to penetrate the meaning of the first Christian centuries, more specifically the centuries before the Mystery of Golgotha happened.

[ 4 ] I would like to give you access, somewhat in the way I have out of Anthroposophy, by means of a presentation, which you can visualise as symptomatic of what history brings. One of the most extinct things belonging in the first Christian centuries was referred to as the Pistis, placed in contrast to the Gnosis. The Gnosis can't be understood if one doesn't know that in that time epoch, in which, let's say, you appeared in the form of a Basilides or Valentinus, people who lived in the spirituality of that time, were fighting a very terrible battle, which can be characterised by them asking a question: What do we poor people have to do on the one hand with the spirit that juts in our souls, and on the other hand our physical body into which our soul likewise juts into? In a terrifying manner this question played out in the soul battle among religious people. The two opposite poles, to a certain extent, of this battle was the Gnosis and Montanism sect.

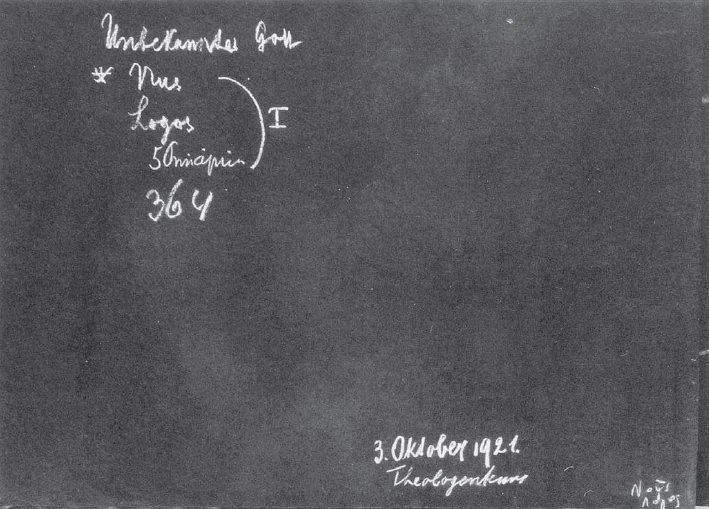

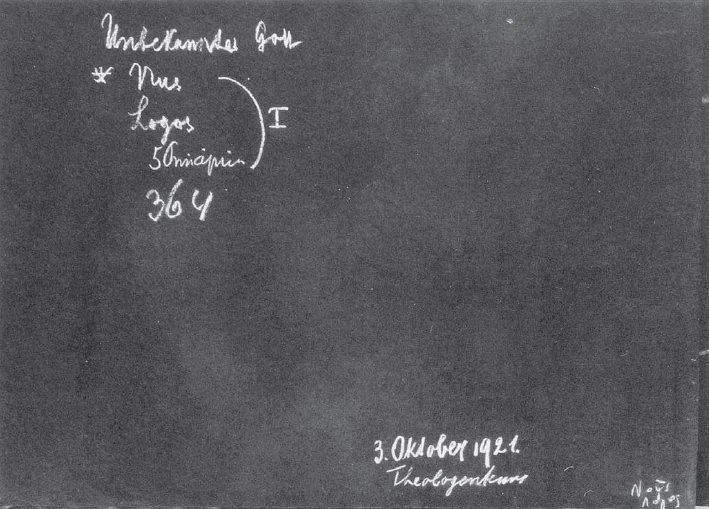

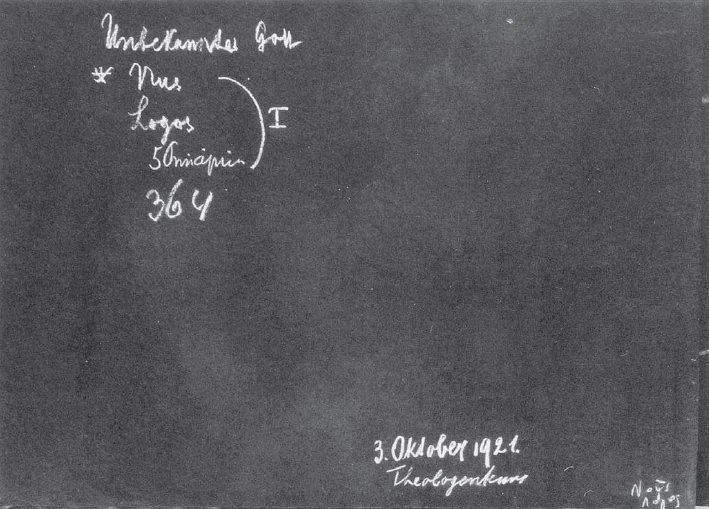

[ 5 ] The Gnosis was, for people who wanted to become Gnostics, being aware that within a person, where the soul resides, the spirit can only be reached through knowledge, through clear, lucid, light-filled knowledge. However, it was already during a time in which intellectualism was being prepared in the dark, in a time when intellectualism was regarded as the enemy of the human soul's relation to the spirit. To a certain extent people prophetically saw how intellectualism would push in, in the future; this arrival of intellectualism was seen as stripping the world of spirituality, wanting to completely make the world void of the Divine, like I have characterised for you yesterday. People saw this and people experienced intellectualism as a danger. People wanted to hold on to something spiritual which didn't come from intellectualism. That's roughly the soul battle Basilides fought, the Gnostic who wanted to stick to what was revealed in the course of the year. He said to himself: When a person submits himself to his forthcoming intellect, then he separates himself from the Divine spirituality of the cosmos; he must connect to what lies in his environment, which has come into being through the Divine spiritual cosmos; he must adhere to that which has the venerable image of cosmic creation in the circling of the world and thus the Divine process in matter; he must adhere to the course of the year.—Basilides did the following: He looked up - but with him it was actually still only tradition, so no longer an inner imaginative perception as in older times, which I characterised as the reading of the movement of the stars—he looked up and said: Last but not least, the spiritual gaze is lost; when we feel, that when we become aware the spiritual gaze is lost, then we talk about the unknown God, the God who can't be grasped in words and concepts, from whom the fist aeon this unknown God manifests himself, revealing himself—this concept of manifestation which later unified things as with Basilides, will be totally misunderstood if compared with what we understand today under "manifestation"; one should not say "it manifests itself" but "it is formed out of," it is individually shaped—out of the unknown God is formed the Nous, which also appeared with Anaxagoras as the first creation of the unknown God.

That is the first principle, which exists in people as a copy, when the human mind, not the intellectual mind but the lively mind I've characterised for you during these days, still existed within Greek philosophy (up to Plato), and which then appeared in a weaker form still in Aristotle.

[ 6 ] What comes next is the Logos, in which from the Nous we descend further down. In human beings it is expressed by perceiving sound and tone. In the neck area we find five other principles which we need not characterise in detail now. With this we have what was first called the holy days of the year, which gives people, when they read the cosmos, an understanding of the human body, leading to the human head organisation.

[ 7 ] Besides these principles we find others in the human organization, 364 in total, which gives 364 + 1=365, the outer symbol which is expressed as the 365 days of the year. The word Day (Tag) originally was inwardly connected to God, so what Basilides, by speaking about 365 days, spoke about 365 gods which all partake in the creation of the human organism. As the last one of the gods—i.e. if you take one plus 364, and then take the last day of the year as a symbol for one God—Basilides saw the God who was worshipped by the Jews in the Old Testament. You see, this is what is extraordinary in the Gnosis, that it is in such a relationship to Jahve, the Jewish God, that he is not the unknown God connected to the Nous and Logos but with the Jewish God as the 365, as the last day of the year.

[ 8 ] By understanding the Gnosis in this way, the experience of the soul was to be permeated spiritually. If I were to give you a characteristic aspect of the Gnosis, in relation to inner human experience it is this: that the Gnostic aspired in everything to penetrate the Highest with knowledge, so that his gaze rose above the Logos up to the Nous. The Gnostic says: In Christ and in the Mystery of Golgotha the Nous is embodied in the human being; not the Logos, the Nous is embodied. This, my dear friends, if it is grasped in a lively way, has a distinct result for our inner soul life. If you consider these things abstractly, as is in our intellectual time presented to many people, well, then it is heard that people in olden times didn't speak about the Logos in which Jesus became flesh, but of the Nous, which became the flesh of Jesus. That's the thing then, if you have pegged such a term. For a person who spiritually lives within a lively experience of concepts, he would not be able to do otherwise, than to grasp such a soul's content, as to imagine sculpturally what the Nous becoming flesh is. The Nous having become flesh however, can't speak; this can't be the Christ, can't go through death and resurrection. The Christ of the Gnostic, which is actually the Nous, could only come as far as being embodied in people; it could not die or accomplish resurrection.

For Basilides, this darkened his observation. His gaze becomes clouded the moment he approaches the last acts of the Mystery of Golgotha with his inner gaze; it clouds his gaze when it comes to dying and resurrection. His gaze is drawn to the route towards Crucifixion, the route to Golgotha of Jesus Christ, but he couldn't accomplish, out of a lively imagination, that the Christ carried the cross to Golgotha, was killed on the cross and resurrected. He regards it in such a way that Simon of Cyrene took the cross from the Christ, that he carried it up to Golgotha, and instead of Christ, that Simon of Cyrene is crucified. This is the Christ imagination of the Gnostic in as far as the image of Basilides appears and is basically the historical expression of the Gnosis.

[ 9 ] So we see how the Christ in his final deed, is omitted by the Gnostic, how the Gnostic can't grasp the final result of Golgotha, how in their imagination the Christ is merely accomplished through the Nous, how it ends at the moment the Christ gives the cross away to Simon of Cyrene. On the one hand we have Gnosis, which is so strongly afraid of intellectualism that it did not let the legitimate power of intellectualism into human vision and as a result could not enter into the last act of the Mystery of Golgotha.

What did the Gnosis do? It stood in quite a lively way, I could say, in relation to the most extraordinary and powerful question of that current age: How does one penetrate the supersensible spirit from which the soul originated?—The Gnostic pointed away from that which somehow wanted to flow in from intellectualism and result in the image of Christ up to the point when he hands the cross to Simon of Cyrene. This is the one side of the human battle which at the time had the result of creating the influence of the great question, which I have set before you. What comes forth from this wrestling?

From all this wrestling another great question arises which became the crux for the Christian Gnostics. My dear friends, because the Gnostics regarded 365 as the Divine god of the Jews, they experienced the Fatherly and the Divine at the end of this row. When the Jews worshiped their god, they experienced it as Fatherly, while what later appeared as the Holy Ghost, they experienced the opposite pole, in the Nous. As a result, the Gnostics gave an answer to the primordial question in the first Christian centuries, an answer which is no longer valid today. Their answer was: The Christ is a far higher creation than the Father; the Christ is essentially equal to the Father. The Father, who finds his most outward, extreme expression in the Jewish god, is the creator of the world, but as the world creator he has, out of its foundations allowed things to be created simultaneously, the good and evil, the good and bad, simultaneously health and illness, the divine and the devilish. This world, which was not made out of love, because it contains evil, the Gnostics contrasted with the more elevated divine nature of the Christ who came from above, downward, carrying the Nous within, who can redeem this world that the creator had to leave un-liberated.

Christ is not essentially the Father, said the Gnostics, the Father essentially stood lower than the Son; the Son as Christ stood higher. This is the fundamental feeling permeating the Gnosis: however, it has been completely obstructed by what later occurred in the Roman Catholic continuation. Basically, we can't look back at what the big question was: How does one relate to the greater Christ in contrast to the less perfect Father? The Gnostic actually saw things in such a way that the Father of the worlds was still imperfect, and only by bringing forth his Son, he created perfection; that through the propagation of his Son, the act of procreation of his Son, He would complete the development of the world.

[ 10 ] In all these things you see exactly what lived in the Gnosis. If we now look at the opposite side, which comes into the strongest expression with Monatunus, already weaker but still clearly with Tertullian, then we look over to those who said to themselves: If we want to reach into the Gnosis, everything disappears; we can't through the outer world, not through the contemplation of the seasons, not through reading the stars, reach the divine, we must enter into man, we must immerse ourselves in man.—

While the Gnosis directed its gaze to the macrocosm, so Mantanismus dived into the microcosm, in the human being himself. Intellectualistic concepts were at that time only in its infancy and could not yet be fully expressed; theology in today's sense did not arise in this way. What existed in all the exercises, in particular those prescribed by Mantanus for his students, were inner stories, something which was enlivened within the students as visions. These atavistic visions for the Montanists were particularly indigenous. All those who were to separate themselves from belonging to the mere pastoral care of the Montanists were allowed to practice, and all of them were allowed to practice to the extent that they could answer the question: how does the soul-spiritual in man, in the microcosm, relate to the physical-bodily aspect?

[ 11 ] During ancient times, long before the Mystery of Golgotha, what I've just said was something obvious; had a self-evident answer. For those who lived in the time epoch of the Mystery of Golgotha, such an obvious answer didn't exist. People first had to dive into physicality. Because a fear existed of bringing intellectualism into this physicality, one entered the corporality with the power of the imagination and we get to know the descriptions of the forming of Montanist visions, which have also disappeared. In descriptions of Montanist visions—and this is characteristic—we always find the repetitive idea of the Christ soon returning in a physical body to the earth. One can't think of Montanism without thinking of the imminent return of the Christ to earthly corporeality. While the Montanist was familiar with the idea of finding the returning Christ, he strongly set before his soul what happened at the cross, what was accomplished through the death on the cross, what is involved in dying, what is involved in resurrection. The re-descent of the Christ, the physical-bodily immersion that takes place, was tinged by materialistic feelings in this view of the Montanists; they lived in the idea that Christ would come again and live in time and space. This was pronounced and those who believed this in the schools were only those who responded to the belief of the imminent coming of Christ Jesus to the earth, where he would stride along as if he is in a physical body.

[ 12 ] This is in contrast to the Gnosis, this is the other pole: it had a different danger, the danger that all historic development of humanity is to be imagined in space and time. The urge to imagine such an idea of the world is what Augustinus for instance experienced in his exchange with the Bishop Faustus. Through Faustus a method of imagination is introduced which is completely tinged with the senses as images presented to Augustinus, and this became a materialistic experience of the world for Augustinus, from where he approached the world. Augustinus' words are gripping: I search for God in the stars, and do not find Him. I search for God in the sun, in the moon, and don't find Him. I search for God in all the plants, in all the animals, and don't find Him. I search for God on the mountains, in the rivers; I don't find Him.—

He means that in all the images there is no inner experience of the Divine, as it is with the Montanists. Through this Augustinus learnt, as it happened in his exchange with Faustus, to recognise materialism. This created his soul battle, which he overcomes by turning to himself, to faith, towards believing what he doesn't know.

[ 13 ] We must let this rise out of history because the important things do not happen in a way, we can control it, by taking a document in hand which has lain in the archives, or by looking at the entire history of these fore-mentioned men from outside—that is an outer assessment of history. The most important part of history takes place in the human soul, in human hearts. We need to look into the soul of Basilides, into the soul of Montanus, into the soul of Faustus, into the soul of Augustinus, if we want to look into what really happened in the historic fields which one then can develop into what actually became a covering of Christianity in the Church of Constantine. The Constantine Church took on the outer life of worldly realms in which the spiritual no longer lived—in the sense of the 13th Chapter of the Mark Gospel—depicted as an already un-deified earth, a perished earth, into which the divine kingdom must again live as brought by him in its real spiritual soul form.

[ 14 ] You see, in the course of both these viewpoints, one on the side the Gnosis which only came up to the Nous, and on the other side Montanism, which remained stuck in a materialistic conception, you see, how in these contrasts present during the first Christian century, the writer of the St John Gospel was situated. He looked on one side to the Gnosis, which he recognised from his view as an error, because it said: In the primordial beginnings was the Nous and the Nous was with God, and God was the Nous, and the Nous became flesh and lived among us; and Simon of Cyrene took the cross from Christ and thus accomplished a human image of what happened on Golgotha, after Christ only went up to carrying the cross and then disappeared from the earthly plane.—For the gaze of the Gnostic Christ disappeared the moment Simon of Cyrene took over the cross. That was a mistake.

Where do you arrive if you succumb to all thought being human and having nothing to do with the spirit? No, this is not the way the writer of John's Gospel experienced it. It was not the Nous which was at the primordial beginnings, not the Nous with God and a veil covering everything which is related to the Christian Mystery, but: In the primordial beginnings was the Logos, and the Logos was with God, and a God was the Logos and the Logos became flesh and lived among us.—So the first actions are connected to the final actions: a unity comes about when we understand it with the spirit. We wish for something which doesn't lift us above human heights, to where we must find the Nous, because that is only one perspective of the spiritual.

Just as much spirit is needed for the spiritual orientation to let people form the idea that Jesus and the Christ God is one, so much spirituality exists in the Logos. When we hold on to the Nous, we only reach Christ; when we hold on to a Montanistic vision we only reach Jesus who in an unbelievable way returns as Christ, but then again only as a physical Jesus. No, we should not turn ourselves to the Nous coming from humanity, we must turn to the Logos, in which the Christ became man and walked among us.

[ 15 ] The origin of the St John Gospel has really come about through an immense spiritual time context. I can't do otherwise, my dear friends, than to make a personal remark here, that I need to experience it as the greatest tragedy of our time, that theologians do not experience the majesty of the John Gospel at all, that out of a deep struggle preceding it, out of a struggle, the big question arose: How can mankind manage to, on the one hand, find a way to his soul-spiritual in the spiritual-supersensible where his own soul-spiritual nature originated from? On the other hand, how can mankind reach an understanding for how his soul is within the physical-bodily nature?

On the one hand the question could be answered by the Gnosis, and on the other hand it could be answered by an imagination towards the Pistis, which then came to Montanism in a visionary manner. The writer of the St John's Gospel was continuously placed in the middle, between these two, and we feel every word, every sentence only intimately if we do it in such a way as it flowed out of the course of the times, and in such a way that you feel the course of time during the Mystery of Golgotha as if it can be experienced forever in the human soul. With an anthroposophic gaze we can look back at the turning point in time, to the most important turning point in the earth, when one wanted to have this experience of adoration of the St John's Gospel. The day before yesterday I said to you, one has, and must, have an experience when one reads the Gospels with an anthroposophical approach, by reading them time and time again. This admiration of the reader is always renewed with each reading by the conviction that one can never learn everything from the Gospels because they go into immeasurable depths. In Gnosis, my dear friends, you can learn everything because it adheres to outer nature and cosmic symbols. In Montanism one can learn all about it because everyone who is familiar with such things knows what a tremendous suggestive persuasiveness all this has, that can be experienced through microcosmic visions, stronger than any outer impression. You must first learn, my dear friends, in order to be able to talk someone out of a vision, you first need to learn how to do it. You could, if you want to convince a person religiously, rather talk him out of what he has experienced with his outer senses, than anything he has experienced as visions, as atavistic clairvoyance, because atavistic visions are far deeper in a person. By allowing atavistic visions into a person, he is far more connected to them than to his sense impressions. It is far easier to determine an error in sense impressions than an error related to visions. Visions are deeply imbedded in the microcosm. Out of such depths everything originated which the writer of John's Gospel saw from the other side, the side of the Montanists.

Montanism was the side of the Charybdis while the Gnosis was the side of the Scylla. He had to get past them both. I feel it at once, as our current tragedy, that our time has been forced—really out of the very superficial honesty, which prevail in such areas—that the Gospel of St John has been completely eliminated and only the Synoptics accepted. If you experience the Gospels through ever greater wonderment at each renewed reading, and when you manage to delve ever deeper and deeper into the Gospels, then it gives you a harmony of the Gospels. You only reach the harmony of the Gospels when you have penetrated St John's Gospel because all together, they don't form a threefold but a fourfold harmony. You won't accomplish, my dear friends, what you have chosen to do in these meetings for the renewal of religion in present time, if you haven't managed to experience the entire depths, the immeasurable depths of the St John's Gospel. Out of the harmony of John's Gospel with the so-called synoptic Gospels something else must come about as had been established by theology. What can really be experienced inwardly as a harmony in the four Gospels must come about in a living way, as the living truth and therefore just life itself. Out of the experience, out of every experience which is deepened and warmed by the history of the origin of Christianity, out of this experience must flow the religious renewal. It can't be a result out of the intellect, nor theoretical exchanges about belief and knowledge, but only from the deepening of the felt, sensed, content which is able to be deepened in such a way as it was able to truly live in the souls of the first Christians.

[ 16 ] Then, my dear friends, we see how Christianity was submerged by all that Christ experienced in Romanism—as I've presented to you—in the downfall of the world. Those who still understand Christ today will have to feel that the downfall is contained in all that is held by the powers of Romanism. By allowing the powers of Romanism to be preserved by the peoples who lived in this Romanism—the Roman written language, the Latin language had long been active—by our preservation of Roman Law, in our conservation of the outer forms of the Roman State, by our even uprooting the northern regions which contained the most elementary Germanic feelings experienced out of quite a different social community, in the Roman State outstripping all that is from the north, we live right up to our present days in a Roman world of decay because in Christendom, as it was considered in the vicinity of Christ Jesus himself, no other site could be found. This is because the Christianity of Constantine, which found such a meaningful symbol in the crowning of Constantine the Great in Rome, was a Christianity which expressed itself in outer worldliness, in Roman legalities. Augustinus already experienced, as I characterised yesterday and today, the feeling in his soul: Oh, what will it be then, if that gets a grip on the world, that which streams out of godless intellectualism, out of godless Romanism into the world? The principle of civil government will become something terrible; the Civitas of people will be opposed by the Civitas Dei, the God State.—So we notice the rise—earlier the indications had already been there, my dear friends—we see an interest emerging that was just seized in the following times in its fullest power in religious fields, that a light is cast on all later religious battles in the soul, which has just felt these religious battles most deeply.

Already with Augustinus this question emerged: How do we save the morality in the face of outward forces of law? How can we save morality, the divinely permeated morality? Into Romanism it can't spread.—This is the striving for internalization we find in the commitments and confessions of Augustinus, if we penetrate them correctly.

[ 17 ] This occurs in the later striving in the most diverse forms. It appears in the tendency towards outer moral stateliness, which had to be developed according to Roman forms of the Roman Papal church, develop through the coronation of the kings becoming Roman emperors, in which the kings were accepted as instruments of the Roman Papal church, which itself was only fashioned out of ungodly Romanism. I speak in the Christian sense, in the sense of the first Christianity, which experienced Romanism as an enemy. How could one escape this which was being prepared? The first way one could get out was to not allow the internalised Christ to submit to the nationalization of morality, as it had evolved in the Roman Papal church. The nationalization, the outer national administration of morality was what Augustinus still accepted on the one hand, while, however, in the depths of his soul there were forces which he rebelled against.

[ 18 ] We see in this rebellion, one could call it, the tendency of morality to withdraw within, at least to save the divinity within morality, according to what one had lost in outer worldliness. We see this morality being turned inward, being searched for as the "little spark" mentioned by Meister Eckhard, by Tauler, by Suso and so on, and how in particular it profoundly, intimately appears in the booklet Theologia Deutch. This, my dear friends is the battle for the moral, which now came to the fore, not to be lost within the divine spirituality, when it has already been lost in outer world knowledge and administration of the world. However, for a long time one was not ready to use such force like Suso regarding morality and seize the divine to penetrate the moral.

[ 19 ] At first it was a question of arranging the whole in a kind of vague form, always envisioning the side of the outside world, for there had to be someone like a Carolus Magnus, who on the one hand was a worldly administrator, and who could transfer the state administration of morality to the crown of the emperor as an outward gesture, while the church worked in the background. It was imagined in such a way, I could say, that it became a kind of moral dilemma, a conscience that has become historical. This started in the 9th, 10th centuries and this inner conscience steered towards people looking at the world, and that man, because he stood in the middle of the search for the divine in the moral, didn't manage it in the world and searched for the enemies in the world which he felt within. Man looked in the world to find enemies. This resulted in the danger of Christians looking for enemies in the outer world, this led, my dear friends, to the mood of the crusades.

[ 20 ] The crusade mood stands in the middle of the quests for internalization, yet people still didn't reach that place within themselves where the divine was grasped through the moral. The crusade mood lived in two forms; it lived above all in the moral impact of Godfrey of Bouillon and his comrades. From them the call went out against Rome: Jerusalem against Rome! To Jerusalem! We want to replace Rome with Jerusalem because in Rome we have become acquainted with outwardness, and in Jerusalem we will perhaps find inwardness, when we relive the Mystery of Golgotha in its holy places.—This is how the imagination came to Godfrey of Bouillon who we may think of as finding the enemy inwardly, even though he still looked for it outwardly, looking for it in the Turks. The striving to turn more inward and there find the ruler of the world, but at the same time to crown a king of Jerusalem, all this expressed itself in the historic mood of the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries. All this lived in the people. For once try to place yourself, in both the worldly and the spiritual reasons of the crusades and you will discover this historical mood everywhere.

[ 21 ] Rome saw this. Rome felt it indeed, something was happening in the north: Jerusalem against Rome. In Rome one felt the externalization, but Rome was careful. Rome already had its prophets; it was careful and looked into the future, seeing what people wanted: Jerusalem against Rome. So it did something which often happens in such cases, it introduced in its own way what the others first wanted, and the Pope allowed his creatures, Peter of Amiens and his supporters, to preach about the crusade in order to carry out from Rome what actually went against it. Study the history with understanding; take it as an impulse and you will see that already the first steps of the crusades took place in what Rome had anticipated and that which Godfrey of Bouillon and his supporters strived for.

[ 22 ] So we see in the historic mood how outer actions were searching for what lay within. I could say we can understand this historic mood in a spiritual way when we see how the Order of the Temple has grown out of the crusades, orders which are already further in their turning within. As a result of the crusades it brought an inwardness with it. It only takes things in such a way that it knows that one does not actually internalize them if one does not penetrate the exterior at the same time, when one doesn't, in order to save the moral, see it as an enemy in an exterior way. As paradoxical as this might appear, my dear friends, what Godfrey of Bouillon saw outwardly in the realm of the Turks, this is like Luther's battle at Wartburg Castle with its devils as an inner power. The struggle is directed inward.

[ 23 ] If you now look at all of this, what appears in programs about such people as Johannes Valentin Andrea, Comenius, what lives in the Bohemian brothers, then you will understand how in the later centuries of the crusades the pursuit of internalization has gone. I must at least mention the most symptomatic picture seemed to me always to be in a single place when I looked at this lonely thinker who lived in Bohemia, the contemporary of Leibniz, Franziskus Josephus von Hoditz und Wolframitz. For the first time, in all clarity—we don't only know this today—he stripped morality of legality. Everywhere in the early days of writing in the Roman spirit, the legal was bound to the moral. What lived in a religious way in most people, lived in a philosophic way in the contemporaries of Leibniz. He wanted the moral element to be purely philosophic. Just like Luther wanted to get the inner justification, because in his time it was no longer possible to get justification in the outer world, so Franziskus Josephus von Hoditz und Wolframitz as a lonely thinker, saw the task: How do I save, purely conceptually, morality from the encirclement and transformation of legality, with those poor philosophic concepts? How do I save the purely human-moral?—He didn't deepen the question religiously. The question was not one-sidedly, intellectually posed by Hoditz—Wolframitz. However, just because it is put philosophically, one notices how he struggles philosophically in the pure shaping of the substantial moral content living in the consciousness.

[ 24 ] In order to understand these times which after all form the foundation of ours, in which the feelings of our contemporaries live—without knowing it—you should, my dear friends, always look back at the deep soul battles experienced in the past, also when a modern person feels that he has "brought it so delightfully far"; by looking back at this time of the most terrible human soul battles, only one period of superstition is seen.

[ 25 ] So, I could say, the historic development of the struggle for morality came about. What was being experienced in this struggle shows up right into our present day, and it can be imposed on the spiritual search into religion, for religious behaviour, even into aberrations. Still, no balance has been found between Pistis and Sophia, between Pistis and Gnosis. This abyss is still gaping in contrast to the writer of the Gospel of St John who had infinite courage to stand above it and find the truth in between it all.

This summoning of strength in the search for the moral, in the will to save the divine, by applying it only to the moral, was felt in their simple, deep but imperfect way by those southern German religious people who are regarded as sectarians today, the Theosophists, who we find on the one hand in Bengel, and on the other, in Oetinger, but who are far more numerous than only in these two. They use all their might to strive, in complete earnestness, for attaining the divine in the moral, yet by trying to attain the divine in morality they realise: We need an eschatology, we need a prophecy, we need foresight into the course of the world's unfolding. This is still the unfulfilled striving of the Theosophists in the first half of the 19th century, started at the end of the 18th century when we must see the dawn of that which was completely buried at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, and which must, from all those who experience the necessity for religious renewal, be seen.

[ 26 ] For this reason, my answers to your wishes which are in pursuit of such religious renewal, can't turn out in any other way than they do. I would quite like to give you what I must believe you are actually looking for.

Vierzehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Meine lieben Freunde! Wir haben gestern begonnen einem Wunsche zu entsprechen, der mir gleich am Anfange des Kurses von Herrn Lizentiat Bock ausgesprochen worden ist, und wir werden ja finden, daß das, was wir nun brauchen zum Ausbau desjenigen, was ich gestern nachmittag ausgeführt habe über den Sakramentalismus im Sinne unserer heutigen Zeit, gerade gewonnen werden kann, wenn wir die Betrachtungen, die möglich und, ich möchte sagen, notwendig sind, anknüpfen an so etwas wie das 13. Kapitel des MarkusEvangeliums. Denn es muß sich uns ja darum handeln, daß wir durchaus wiederum in einem bestimmten Sinne ernstzunehmen versuchen das Heraussprechen aus dem lebendigen Worte. Es erscheint mir unmöglich, daß in der Zukunft ein Seelsorgerwirken sich ausbilden kann, ohne daß man selber sich hinentwickelt zu diesem Handhaben des lebendigen Wortes, eben zu dem Erleben des Wortes. Es ist aber unmöglich für den heutigen Menschen, der so stark in den Intellektualismus verstrickt ist, dazu zu kommen, das lebendige Wort in sich zu handhaben, ohne eine historische Vertiefung. Denn es ist ja nun einmal so, daß in der Handhabung der intellektualistischen Begriffe und Ideen wir es nur zu tun haben mit dem toten Worte, mit dem Leichnam des Logos, und daß wir es erst zu tun bekommen mit dem lebendigen Worte, wenn wir gewissermaßen durchdringen durch die Schicht, in der heute der Mensch einzig und allein lebt, durch die Schicht der toten, der leichnamsgemäßen Worte.

[ 2 ] Meine lieben Freunde, die katholische Kirche hat in einer gewissen Beziehung gut verstanden, den Zugang zu diesem lebendigen Worte bei denen zu verlegen, zu verbauen, welche nach ihrer Meinung die richtigen Gläubigen sein sollen. In der Seelsorge beachtet die katholische Kirche in einem gewissen Sinn dieses Lebendigwerden des Wortes ja schon, aber auch da gewissermaßen in einem äußerlichen Sinn. Das alles kann uns nur verständlich werden, wenn wir das, was ich gestern vorgebracht habe, tiefer durchdenken, und wenn wir es noch durch einiges Weiterdringen jetzt zur Klarheit bringen. Ich sage, die katholische Kirche hat sehr gut verstanden, in dieser Beziehung das Leben des Wortes auszutilgen, denn es gehört einmal zu den bedeutsamsten Zeitaltern der ganzen Menschheitsentwickelung dasjenige, was sich zugetragen hat kurze Zeit vor und etwa drei Jahrhunderte nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha gerade im zivilisierten Teil der Menschheit.

[ 3 ] Wenn heute unsere Gegenwartsmenschen fragen nach dem Wesen der Gnosis, zum Beispiel nach dem Wesen der montanistischen Häresie, dann können sie sich nach der gegenwärtigen Seelenverfassung im Grunde genommen gar nichts Rechtes darunter vorstellen. Denn das, was äußerlich Aufschluß geben würde, ist sorgfältig ausgetilgt worden von der werdenden Kirche, und die Dinge, die heute die Archäologen, die Altertumsforscher, die Philosophen aufdecken von jenseits des eben charakterisierten Zeitraumes, die werden zwar dem Wortlaute nach entziffert, aber die Entzifferung bedeutet kein Verständnis. Alles das muß eigentlich anders gelesen werden, wenn man zu einem wirklichen Seeleninhalte der alten Zeiten kommen will. Es ist ja zum Beispiel der modernen Menschheit möglich, gerade die allen wirklichen Sinn des Orients austilgenden Deussenschen Übersetzungen für etwas Großes zu halten, während man nicht besser alles Verständnis für dasjenige, was Deussen übersetzt hat, austilgen kann, als wenn man sich einer solchen Deussenschen Übersetzung hingibt. Aber um das zu verstehen, muß man eben eindringen in den Sinn der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte, beziehungsweise der Jahrhunderte, bevor das Mysterium von Golgatha erschienen ist.

[ 4 ] Ich möchte Ihnen den Zugang ein wenig in der Art geben, wie ich es aus der Anthroposophie heraus tun muß, durch eine Darstellung, die an Symptomatischem das Geschichtliche zur Anschauung bringt. Zu dem Ausgetilgtesten gehört ja das, was man in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten im Gegensatz zur Pistis bezeichnete als die Gnosis. Die Gnosis ist gar nicht zu verstehen, wenn man nicht weiß, daß in dem Zeitalter, in dem sie, sagen wir, in der Form des Basilides oder des Valentinus [auftrat], bei denjenigen Menschen, die drinnenstanden in dem geistigen Leben der damaligen Zeit, ein ganz furchtbarer Kampf ausgefochten wurde, der sich etwas charakterisieren läßt, wenn man die Frage hinstellt: Was fangen wir armen Menschen jetzt an auf der einen Seite mit dem Geiste, der hereinragt in unsere Seele, und auf der anderen Seite mit unserer physischen Leiblichkeit, in die unsere Seele ebenso hereinragt? In einer furchtbaren Weise hat sich diese Frage als Seelenkampf gerade bei den religiösesten Menschen der angezeigten Jahrhunderte abgespielt. Und die zwei Gegenpole gewissermaßen in diesem Kampfe stellen dar die Gnosis und der Montanismus.

[ 5 ] Die Gnosis besteht eigentlich darin, daß sich die Menschen, die Gnostiker werden, bewußt sind: Man kann zu demjenigen, in dem die Seele urständet, zu dem Geistigen nur kommen durch Erkenntnis, durch klare, helle, lichtvolle Erkenntnis. - Aber es war schon die Zeit, in welcher sich doch im Dunkeln vorbereitete der Intellektualismus, die Zeit, in der man den Intellektualismus als den Feind des menschlichen Seelenbezuges zum Geistigen betrachtete. Man sah gewissermaßen prophetisch in die Zukunft, wie der Intellektualismus heranrückt, man sah gewissermaßen schon dieses Kommen des Intellektualismus, der die Welt vollständig entgeistigen, vollständig entgöttlichen wollte, wie ich das gestern charakterisiert habe. Man sah das, und man fühlte sich dem Intellektualismus als einer Gefahr gegenüber. Man wollte mit allen Fasern festhalten an einem Geistigen, das nicht erfaßt wird von dem Intellektualismus. Das ist ungefähr der Seelenkampf, den Basilides ausgefochten hat, der Gnostiker, der sich halten wollte an dasjenige, was sich im Jahreslaufe offenbaren will. Er sagte sich: Wenn der Mensch sich ganz überläßt seinem fortfließenden Intellekt, so trennt er sich von dem göttlich-geistigen Kosmos; er muß sich halten an dasjenige, was in der Umgebung liegt, die durch den göttlich-geistigen Kosmos zustandegekommen ist; er muß sich halten an das, was im Weltenkreislauf das ehrwürdige Bild des kosmischen Schaffens hat, also des Wirkens des Göttlichen im Materiellen; er muß sich halten an das Jahr. - Und Basilides tut das folgende: Er schaut hinauf — aber bei ihm ist es eigentlich nur noch Tradition, also nicht mehr in innerer imaginativer Anschauung wie in alten Zeiten, wie ich das charakterisiert habe als das Lesen in den Sternenbewegungen -, er schaut hinauf und sagt: Zu allerletzt verfließt der geistige Blick; wenn wir empfinden, gewahr werden, wie der geistige Blick verfließt, dann reden wir von dem unbekannten Gott, von dem Gott, der in keine Worte und Begriffe zu fassen ist, von dem ersten Äon, und aus diesem unbekannten Gotte manifestiert sich, offenbart sich heraus — dieser Begriff der Manifestation, der später die Dinge verunziert, ist bei Basilides noch gar nicht in der gleichen Weise zu verstehen, wie wir heute «Manifestation» verstehen, man sollte nicht sagen «es manifestiert sich», sondern «es gestaltet sich heraus», ganz individuell sich gestaltend —, aus dem unbekannten Gotte gestaltet sich dasjenige heraus, was der Nous ist, der auch bei Anaxagoras auftritt, gewissermaßen die erste Schöpfung des unbekannten Gottes. Das ist das erste Prinzip, das im Menschen sein Abbild hat, wenn der Mensch sich seinem Verstand, aber jetzt nicht dem [intellektuellen] Verstand, sondern dem Ihnen in diesen Tagen charakterisierten lebendigen Verstand hingegeben hat, den die Menschen noch hatten innerhalb der griechischen Philosophie [bis Plato], und den in abgeschwächter Form Aristoteles noch hatte.

[ 6 ] Das, was als das nächste herauskommt, ist der Logos, indem man vom Nous mehr nach unten geht. Im Menschen spricht sich das aus, indem er Lautendes und Tönendes empfindet. Dann waren in der Halsgegend Abbilder zu finden von fünf anderen Prinzipien, die wir jetzt nicht im einzelnen zu charakterisieren brauchen. Damit haben wir dasjenige, was man nannte den ersten heiligen Tag des Jahres, der dem Menschen, wenn er ihn im Kosmos lesend erfaßt, das gibt, was ihn zum Verständnis des menschlichen Kopfes, der menschlichen Kopforganisation führt.

[ 7 ] Außer diesen Prinzipien finden sich in der menschlichen Organisation noch andere Prinzipien, insgesamt 364, das gibt dann 364 + 1 = 365, was äußerlich symbolisch sich schon in den 365 Tagen des Jahres ausdrückt. Das Wort Tag hing ursprünglich inniger zusammen mit Gott, so daß Basilides, indem er von 365 Tagen sprach, ebenso sprechen konnte von 365 Göttern, die an dem Aufbau der menschlichen Organisation beteiligt sind. Als den letzten der Götter — also wenn Sie Eins nehmen und dann 364, und dann den letzten Namen, also den letzten Tag des Jahres, als Symbolum für einen Gott — sieht Basilides den Gott, den die Juden des Alten Testamentes verehrt haben. Sehen Sie, das ist das Eigentümliche der Gnosis, daß sie sich gerade zu dem Judengott Jahve so verhält, daß er nicht etwa der unbekannte Gott ist, der mit dem Nous und mit dem Logos zu tun hat, sondern daß der Judengott der letzte ist der 365, der letzte der 365 Tage des Jahres.

[ 8 ] Dadurch, daß das so aufgefaßt wurde in der Gnosis, wurde die Empfindung der Seele nach dem Spirituellen hinaufgedrängt. Wenn ich Ihnen ein charakteristisches Merkmal der Gnosis angeben soll in bezug auf das innere menschliche Erleben, so ist es dieses, daß der Gnostiker alles Streben hatte, bis zum Höchsten hinauf mit der Erkenntnis zu dringen, so daß sich sein Blick über den Logos hinauf zu dem Nous erhob. Der Gnostiker sagte: In Christus und im Mysterium von Golgatha erschien der Nous menschlich verkörpert; nicht der Logos, der Nous erschien menschlich verkörpert. Das hat aber, meine lieben Freunde, wenn man es lebendig erfaßt, eine ganz bestimmte Folge für unser inneres Seelenleben. Wenn man die Dinge so abstrakt hinstellt, wie sie heute im intellektualistischen Zeitalter vielfach vor die Leute hingestellt werden, nun ja, dann hört man, die Menschen der älteren Zeiten hätten nicht von dem Logos gesprochen, der in Jesus Fleisch geworden ist, sondern von dem Nous, der in Jesus Fleisch geworden ist. Damit ist die Sache dann aus, wenn man einen solchen Begriff hingepfahlt hat. Derjenige aber, der im lebendigen Erleben des Begrifflichen geistig drinnensteht, der kann nicht anders, indem er einen solchen Seeleninhalt faßt, als sich plastisch gestaltet das vorzustellen, was fleischgewordener Nous ist. Fleischgewordener Nous aber kann nicht sprechen, das kann nicht der Christus sein, kann nicht durch Tod und durch Auferstehung gehen. Der Christus der Gnostiker, der eigentlich der Nous ist, konnte nur so weit kommen, daß er sich im Menschen verkörperte, er konnte aber nicht bis zum Sterben und zur Auferstehung kommen. Dadurch verdunkelt sich für Basilides zum Beispiel die Anschauung. Ihm trübt sich der Blick in dem Moment, wo er sich mit seinem inneren Schauen den letzten Akten des Mysteriums von Golgatha nähert; ihm trübt sich der Blick, wenn es zum Sterben und zur Auferstehung kommt. Der Blick wurde hingeworfen auf den Kreuz-Gang, auf den Golgatha-Gang des Christus Jesus, aber er konnte aus einer lebendigen Vorstellung das nicht vollenden, daß der Christus das Kreuz bis Golgatha getragen hat, daß er ans Kreuz geschlagen worden ist und auferstanden ist. Ihm stellt sich in den Blick hinein, daß Simon von Kyrene [dem Christus] das Kreuz abgenommen hat, daß er es bis Golgatha hinaufgetragen hat, und daß anstelle des Christus Simon von Kyrene gekreuzigt worden ist. Das ist die Christus-Vorstellung der Gnostiker, insofern die Gnosis in der Gestalt des Basilides auftritt, und im Grunde genommen ist das die historische Gestalt der Gnosis.

[ 9 ] So also sehen wir, wie der Christus mit seiner letzten Tat dem Gnostiker entfällt, wie der Gnostiker nicht festhalten kann das letzte Ereignis von Golgatha, wie sich seine Vorstellung von Christus bloß erfüllt durch den Nous, wie sie sich ihm vollendet in dem Augenblick, wo Christus das Kreuz dem Simon von Kyrene abgibt. Da haben wir auf der einen Seite die Gnosis stehen, die sich so stark fürchtet vor dem Intellektualismus, daß sie auch die berechtigte Kraft des Intellektualismus nicht in das menschliche Schauen einließ und daher mit dem Schauen nicht hinkommen konnte bis zu dem letzten Akte des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Was tat die Gnosis? Sie stand ganz lebendig darinnen in der, ich möchte sagen, großartigsten und gewaltigsten Frage des damaligen Zeitalters: Wie dringt der Mensch zu dem, worin seine Seele urständet im Geistig-Übersinnlichen? Der Gnostiker wies weg dasjenige, was irgendwie einfließen wollte aus dem Intellektualistischen, und es ergibt sich ihm das Bild [des Christus nur] bis zur Abnahme des Kreuzes durch Simon von Kyrene. Das ist die eine Seite des menschlichen Kampfes, der dazumal entstanden ist unter dem Einfluß der großen Frage, die ich vor Sie hingestellt habe. Und was ging aus diesem Ringen hervor? Aus diesem Ringen ging die andere große Frage hervor, die jetzt für die christlichen Gnostiker eine Crux wurde. Meine lieben Freunde, indem die Gnostiker das 365. Göttliche als den Judengott ansahen, empfanden sie das Väterliche in dem Göttlichen gerade am Ende dieser Reihe. Wo die Juden ihren Gott verehrten, da empfanden sie das Väterliche, während sie dasjenige, was später als der Heilige Geist zum Vorschein kam, empfanden in dem anderen Pole, in dem Nous. Und daher gaben die Gnostiker auf eine bestimmte christliche Urfrage der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte eine Antwort, die heute gar nicht mehr gewürdigt wird, sie gaben die Antwort: Der Christus ist ein viel höheres Geschöpf als der Vater, der Christus ist nicht wesensgleich dem Vater. Der Vater, der seinen äußersten, extremsten Ausdruck in dem Judengott fand, ist der Schöpfer der Welt, aber der Schöpfer der Welt war genötigt, aus seinen Untergründen eine Welt hervorgehen zu lassen, die ganz zur gleichen Zeit hervorbringt das Gute und das Böse, das Gute und das Schlechte, die zu gleicher Zeit hervorbringt Gesundheit und Krankheit, die zu gleicher Zeit hervorbringt das Heilige und das Teuflische. Dieser Welt, die nicht gemacht war aus Liebe, weil sie das Böse enthält, stellten die Gnostiker als das höhere Göttliche den Christus entgegen, der von oben herunter kam, der den Nous in sich trägt, der diese Welt erlösen kann, die der Schöpfer unerlöst lassen mußte. Der Christus ist nicht wesensgleich dem Vater, sagte der Gnostiker, der Vater ist dem Wesen nach viel tieferstehend als der Sohn, der Sohn ist als der Christus der Höherstehende. Das ist etwas, was als eine Grundempfindung durch die Gnosis hindurchgeht; es ist allerdings vollständig verbaut worden durch das, was später in der römisch-katholischen Kontinuation eingetreten ist. Auf das kann man im Grunde genommen gar nicht mehr zurückschauen, daß einmal die große Frage da war: Wie verhält man sich zu dem größeren Christus gegenüber dem weniger vollkommenen Vater? Die Gnostiker haben eigentlich die Sache so angesehen, daß der Vater der Welten noch unvollkommen war, daß er erst in seinem Sohne das Vollkommenere hervorbringen konnte, daß er die Fortpflanzung zum Sohne, die Zeugung des Sohnes tat, um die Weltentwickelung zu vervollständigen.

[ 10 ] In allen diesen Dingen sehen Sie dezidiert dasjenige, was in der Gnosis lebte. Sehen wir jetzt nach der anderen Seite hinüber, die am stärksten bei Montanus, schwächer schon, aber doch noch deutlich, bei Tertullian zum Ausdruck gekommen ist; sehen wir hinüber zu denjenigen, welche sich gesagt haben: Wenn wir hinaufkommen wollen zur Gnosis, da entschwindet ja alles; wir können nicht durch die äußere Welt, nicht durch die Betrachtung des Jahres, nicht durch das Lesen in den Sternen zu dem Göttlichen aufrücken, wir müssen in den Menschen untertauchen, wir müssen in den Menschen hinein. — Wie die Gnosis den Blick hinauslenkt in den Makrokosmos, so taucht der Montanismus unter in den Mikrokosmos, in den Menschen selber. Intellektualistische Begriffe waren [damals] erst im Anzug, die konnte er noch nicht völlig hervorbringen; 'Theologie im heutigen Sinn ergab sich auf diesem Wege nicht. Was sich aber ergab durch alle die Übungen, die insbesondere Montanus seinen Schülern vorschrieb, das waren innere Gesichte, das war dasjenige, was im Innern des Menschen auflebt in atavistischen Visionen. Diese atavistischen Visionen waren insbesondere bei den Montanisten heimisch. Man ließ alle diejenigen üben, die sich absondern sollten von dem Zugehören zur bloßen Seelsorge unter den Montanisten, man ließ diese alle soweit üben, daß sie sich die Frage beantworten konnten: Wie hängt das Geistig-Seelische im Menschen, im Mikrokosmos, zusammen mit dem Leiblich-Physischen?

[ 11 ] Für ältere Zeiten, die lange vorangingen dem Mysterium von Golgatha, war das, wie ich schon gesagt habe, etwas Selbstverständliches, es ergab sich eine selbstverständliche Antwort. Für diejenigen, die im Zeitalter des Mysteriums von Golgatha lebten, ergab sich eine solche selbstverständliche Antwort nicht. Man mußte erst untertauchen in die Leiblichkeit. Weil man aber fürchtete, in diese Leiblichkeit den Intellektualismus mitzunehmen, begab man sich in die Leiblichkeit hinunter mit der Kraft der Imagination, und es bildete sich dasjenige aus, was wir in den allerdings auch verschwundenen Beschreibungen der Visionen der Montanisten kennenlernen. In diesen Beschreibungen der Visionen der Montanisten finden wir — und das ist für sie charakteristisch —, wir finden immer wiederum die Vorstellung von dem baldig im physischen Erdenleibe wiederkommenden Christus. Der Montanismus ist nicht zu denken ohne die prophetische Empfindung des bald im Erdenleibe wiederkommenden Christus. Weil der Montanist seine Vorstellungen gewöhnt hat an das, was er im kommenden Christus findet, stellt sich vor seine Seele nun stark dasjenige hin, was am Kreuze geschieht und dasjenige, was sich nach dem Kreuzestode erfüllt, was ins Sterben hineingeht, was zur Auferstehung hingeht. Das Wiederherunterkommen des Christus, das Wiederuntertauchen in das leiblichphysische Leben, das nimmt in der Anschauung [der Montanisten] durchaus von materialistischen Empfindungen tingierte Formen an; in dem zeitlich und räumlich erfüllten Sein des wiederkommenden Christus lebt man. Man sprach das aus, und gläubig innerhalb dieser Schule waren nur diejenigen, welche eingingen auf diesen Glauben an das baldige physische Herannahen des Christus Jesus auf die Erde, wo er so wandeln wird, daß er eben im physischen Leibe wandelt.

[ 12 ] Das war der Gegensatz der Gnosis, das war der andere Pol; er hatte die andere Gefahr, die Gefahr, alle geschichtliche Entwickelung der Menschheit sich in Raumes- und in Zeit-Bildern vorzustellen. Gerade der Drang, ein solches [Bild] von der Welt sich vorzustellen, das ist es, was zum Beispiel Augustinus im Wechselgespräch mit dem Bischof Faustus erlebte. Ihm wurde durch Faustus eine Vorstellungsweise vorgebracht, die ganz und gar in sinnestingierten Bildern vor des Augustinus Anschauung drängte, und das wurde von Augustinus empfunden als eine materialistische Vorstellung der Welt, aus der er herausstrebte. Ergreifend sind ja die Worte, die wir bei Augustinus finden: Ich suchte Gott in den Sternen, ich fand ihn nicht. Ich suchte Gott in der Sonne, im Monde, ich fand ihn nicht. Ich suchte Gott in allen Pflanzen, in allen Tieren, ich fand ihn nicht. Ich suchte Gott auf Bergen, in Flüssen, ich fand ihn nicht. Ich suchte Gott in allen Gestaltungen der Erde, ich fand ihn nicht, — Er meint, in all den Abbildern ergab sich ihm nicht das innere Erleben der Gottheit, wie es sich den Montanisten ergab. Dadurch lernt Augustinus ja doch eine Gestaltung der christlichen Entwickelung kennen, wie sich ihm das im Gespräch mit Faustus ergab, dadurch lernt Augustinus den Materialismus kennen. Das bildet seinen Seelenkampf, den er dadurch überwindet, daß er sich hinwendet [zum Glauben], dadurch, daß er glaubt, was er nicht weiß.

[ 13 ] Das müssen wir nur aus der Geschichte herauskommen lassen, denn das Wichtigste spielt sich nicht so ab, daß wir es beherrschen können, indem wir die Dokumente in die Hand nehmen, die in Archiven liegen oder indem wir auf die ganze Geschichte dieser vier damaligen Männer von außen hinschauen — das ist äußere Geschichtsauffassung. Der wichtigste Teil der Geschichte spielt sich ab in den menschlichen Seelen, in den menschlichen Herzen. Wir müssen hineinschauen in die Seele des Basilides, in die Seele des Montanus, in die Seele des Faustus, in die Seele des Augustinus, wenn wir in dasjenige hineinblicken wollen, was sich eigentlich in jenen historischen Kämpfen abgespielt hat, die sich dann zu dem entwickelt haben, was eigentlich eine Zudeckung des Christentums wurde in der Konstantinischen Kirche. Die Konstantinische Kirche hat ein äußeres Leben von den weltlichen Reichen hergenommen, in denen nicht mehr das Geistige lebt, sie hat ihr Leben von dem hergenommen, was der Christus — im Sinne des 13. Kapitels des MarkusEvangeliums — bezeichnet als die bereits entgötterte Erde, als die untergegangene Erde, in die das durch ihn gebrachte göttliche Reich sich erst wiederum hineinleben muß in seiner wirklichen geistigseelischen Gestalt.

[ 14 ] Sehen Sie, in den Aufgang dieser beiden Weltanschauungen, der Gnosis auf der einen Seite, die nur bis zum Nous kam, und des Montanismus auf der anderen Seite, der eben steckengeblieben ist in einer materialistischen Auffassung, in diesen Gegensatz, wie er vorhanden war im ersten christlichen Jahrhundert, ist hineingestellt der Schreiber des Johannes-Evangeliums. Er schaut auf der einen Seite hin auf die Gnosis, die er seinerseits als eine Verirrung ansieht, weil sie sagt: Im Urbeginne war der Nous und der Nous war bei Gott, ein Gott war der Nous, und der Nous ist Fleisch geworden und hat unter uns gewohnt; und Simon von Kyrene hat dem Christus das Kreuz abgenommen und hat in einem Menschenbilde dasjenige vollzogen, was dann [auf Golgatha] erfolgte, nachdem der Christus nur bis zur Kreuztragung gegangen und dann von dem Irdischen hinwegverschwunden ist. - Vor dem Blick des Gnostikers verschwindet ja der Christus allerdings in dem Augenblicke, als er Simon von Kyrene das Kreuz übergibt. Das war eine Abirrung. Wohin kommt man, wenn man darauf sich einläßt, alles Gedankliche unter den Menschen zu lassen und nicht mehr haben zu wollen das Geistige? Nein, so empfindet der Schreiber des Johannes-Evangeliums, so ist es nicht. Nicht war im Urbeginne der Nous, nicht war der Nous bei Gott und ein Schleier liegt über all dem, was mit dem ChristusMysterium zusammenhängt, sondern: Im Urbeginne war der Logos, und der Logos war bei Gott, und ein Gott war der Logos und der Logos ist Fleisch geworden und hat unter uns gewohnet. — So verbindet sich dasjenige, was die ersten Akte des ganzen GolgathaDramas sind, mit den letzten Akten: eine Einheit wird daraus, wenn wir es erfassen im Geiste. Wir wollen etwas, das uns nicht in übermenschliche Höhen hinausführt, wohin uns der Nous führen muß, weil der nur die eine Perspektive des Geistigen ist. Soviel Geistiges, daß dieses Geistige hinreicht, um den Menschen Jesus und den Gott Christus in einer Gestalt zu begreifen, soviel Geistiges liegt in dem Logos. Wenn wir uns an den Nous halten, kommen wir nur zum Christus, wenn wir uns an das montanistische Sehen halten, kommen wir nur zu dem Jesus, der in unbegreiflicher Weise als der Christus wiederkommt, wiederum nur als der physische Jesus. Nein, wir müssen uns nicht hinwenden zu dem uns aus der Menschheit herausreißenden Nous, wir müssen uns hinwenden zum Logos, der in dem Christus Mensch geworden ist und unter uns gewandelt ist.

[ 15 ] Es ist wirklich in einen großen geistigen Zeitzusammenhang hineingestellt der Ursprung des Johannes-Evangeliums. Ich kann nicht anders, meine lieben Freunde, als hier die persönliche Bemerkung zu machen, daß ich es empfinden muß als etwas, was zum Tragischsten unserer Zeit gehört, daß von der Theologie so gar nicht empfunden wird die Hoheit des Johannes-Evangeliums, das aus einem der tiefsten Kämpfe hervorgegangen ist, aus dem Kampfe um jene große Frage: Wie kommt der Mensch zurecht, um auf der einen Seite den Weg zu finden mit seinem Geistig-Seelischen hinauf in das Geistig-Übersinnliche, worin sein Geistig-Seelisches urständer? Wie kommt er auf der anderen Seite zum [Verstehen] des Urständens der Seele im Physisch-Leiblichen? - Die eine Seite [der Frage] konnte beantworten die Gnosis, die andere Seite konnte beantworten die zur Imagination werdende Pistis, die dann im Montanismus in visionärer Weise zutagegetreten ist. Der Schreiber des Johannes-Evangeliums war durchaus in die Mitte dieser [beiden] hineingestellt, und wir empfinden jedes Wort, jeden Satz nur intim, wenn wir ihn so empfinden, wie er herausgeflossen ist aus dem Gang der Zeit, und zwar so, wie sich im Gange der Zeit zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha das Ewige in den menschlichen Seelen einleben konnte. Mit anthroposophischem Blick muß man wieder zurückschauen in die Zeitenwende, in die wichtigste Erdenzeitenwende, wenn man dieses Gefühl der Bewunderung des Johannes-Evangeliums empfinden will. Ich habe Ihnen vorgestern gesagt, eine Empfindung hat man und muß man haben, gerade wenn man sich anthroposophisch dem Lesen der Evangelien nähert und dieses Lesen immer wieder und wiederum wiederholt. Das ist die aus der Bewunderung, aus der bei jedem Lesen sich immer erneuernden Bewunderung des Evangeliums sich einstellende Überzeugung, daß man an den Evangelien niemals auslernen kann, weil sie in unermeßliche Tiefen hineinführen. Und in der Gnosis, meine lieben Freunde, konnte man auslernen, weil sie sich hält an äußere Natur- und kosmische Symbole, im Montanismus konnte man auslernen, denn das weiß jeder, der mit solchen Dingen bekannt ist, welch ungeheuere suggestive Überzeugungskraft alles dasjenige hat, was man im Mikrokosmos als Vision erlebt, stärker als jeder äußere Eindruck. Einem Menschen eine Vision auszureden, meine lieben Freunde, das müssen Sie nur erst gelernt haben. Sie können, wenn Sie einen Menschen religiös überzeugen wollen, ihm viel eher das ausreden, was er mit seinen äußeren Sinnen erlebt hat, als irgend etwas, was er als Visionen, als atavistisches Hellsehen erlebt hat, weil Visionen atavistischer Art tiefer als die Sinne im Menschen sitzen. Sitzen heute Visionen atavistischer Art im Menschen, dann ist der ganze Mensch viel tiefer mit ihnen verbunden, als er mit seinen Sinneseindrücken verbunden ist. Sie kommen viel leichter zurecht, einen Irrtum festzustellen in bezug auf Sinneseindrücke, als einen Irrtum, der sich bezieht auf Visionen. Die Visionen sitzen tief unten im Mikrokosmos. Und aus solchen Tiefen ist alles dasjenige hervorgegangen, was nun der Schreiber des Johannes-Evangeliums nach der anderen Seite[, der Seite des Montanismus] gesehen hat. Der Montanismus war die Seite der Charybdis, während die Gnosis die Seite der Skylla war. Zwischen beiden mußte er hindurch. Und ich empfinde es einmal als das Tragische unserer Zeit, daß unsere Zeit genötigt war — nun wiederum aus eben der oberflächlichen Ehrlichkeit, die heute auf solchen Gebieten waltet —, das Johannes-Evangelium mehr oder weniger ganz auszuschalten und nur die Synoptiker hinzunehmen. Wenn man das erlebt, wie man die Evangelien immer mehr und bewundernd erlebt bei jedem erneuten Lesen, und wenn man dazu kommt, immer tiefer und tiefer erlebend in die Evangelien einzudringen, dann ergibt sich einem der Zusammenklang der Evangelien. Sie haben das Zusammenklingen der Evangelien erst, wenn Sie auch das Johannes-Evangelium durchdrungen haben, weil das Ganze nicht ein Dreiklang, sondern ein Vierklang ist. Und Sie werden nicht zu dem kommen, meine lieben Freunde, was Sie sich vorgenommen haben, indem Sie zu diesen Besprechungen sich entschlossen haben, hinzuschauen auf dasjenige, was zur religiösen Erneuerung in der Gegenwart drängt, wenn Sie nicht dazu kommen, die ganze Tiefe, die unermeßliche Tiefe gerade des Johannes-Evangeliums zu empfinden. Aus dem Zusammenklang des Johannes-Evangeliums mit den sogenannten synoptischen Evangelien muß etwas anderes heute zustandekommen, als die Theologie zustandegebracht hat. Es muß schon das zustandekommen, was innerlich als ein Zusammenklang an den vier Evangelien wirklich erlebt werden kann als der lebendige Weg, die lebendige Wahrheit und dadurch eben das Leben selber. Aus der Empfindung heraus, aber aus jener Empfindung heraus, die vertieft und erwärmt ist an der Entstehungsgeschichte des Christentums, aus dieser Empfindung heraus muß die religiöse Erneuerung erfolgen. Nicht aus dem Intellekt heraus kann sie erfolgen und auch nicht aus einem theoretischen Herumdiskutieren über Glauben und Wissen, sondern lediglich aus der Vertiefung des Empfindungsgehaltes, der sich so zu vertiefen vermag, daß er wirklich in den Seelen der ersten Christen leben konnte.

[ 16 ] Und dann finden wir, meine lieben Freunde, wie das Christentum untertaucht in dasjenige, was das Römertum war, in dem der Christus empfunden hat — wie ich Ihnen auseinandergesetzt habe — die untergehende Welt. Diejenigen, die den Christus heute noch verstehen, werden fühlen müssen, der Untergang ist in alle dem enthalten, was die Kräfte des Römertums enthält. Indem wir die Kräfte des Römertums fortkonserviert haben, indem in die Völker sich eingelebt hat der Romanismus — die römische Schriftsprache, die lateinische Sprache hat ja lange gewirkt —, indem wir konserviert haben das römische Gesetz, indem wir konserviert haben die äußeren Formen des römischen Staatstums, indem sogar in den nördlichen Gegenden ausgetilgt worden ist, was aus elementarem germanischen Fühlen als ganz andere soziale Gemeinschaft empfunden wurde, indem das römische Staatstum alles Nördliche überflügelt hat, lebt bis in unsere Tage hinein das Römertum als die untergehende Welt, in der das Christentum, so wie es gedacht war in der Umgebung des Christus Jesus selber, nicht mehr eine Stätte gefunden hat. Denn das konstantinische Christentum, das dann in der Krönung Konstantins des Großen in Rom ein so bedeutsames Symbolum gefunden hat, dieses Christentum ist dasjenige, das sich eingelebt hat in die äußere Weltlichkeit, in die römische Gesetzmäßigkeit. Schon bei Augustinus, indem er so empfand, wie ich es gestern und heute charakterisiert habe, entstand die Seelenempfindung: ©, was wird es dann sein, wenn nun dasjenige die ganze Welt ergreift, was aus dem entgöttlichten Intellektualismus, aus dem entgöttlichten Römertum, in die Welt hineinströmt? Die Civitas wird eine furchtbare werden; dieser Civitas der Menschen muß entgegengestellt werden die Civitas Dei, der Gottesstaat. - Und so sehen wir auftauchen — vorher waren die Anzeichen schon da, meine lieben Freunde -, so sehen wir auftauchen ein Interesse, das gerade von den folgenden Zeiten auf religiösem Gebiete mit voller Macht ergriffen wurde, und das ein Licht wirft auf alle späteren religiösen Kämpfe in den Seelen, die gerade diese religiösen Kämpfe am tiefsten erfühlt haben. Es taucht bereits bei Augustinus die Frage auf: Wie retten wir das Moralische gegenüber dem äußerlichen Gesetzeshaften? Wie retten wir die Moral, die gottdurchtränkte Moral, wie retten wir sie? Im Römertum kann sie sich nicht ausbreiten. — Das ist das Streben nach Verinnerlichung, das wir in den Bekenntnissen, den Konfessionen des Augustnus finden, wenn wir sie richtig durchdringen.

[ 17 ] Und das ist das ganze spätere Ringen, es tritt in den verschiedensten Gestalten wiederum auf. Es tritt auf zunächst in der Hinneigung zu einer äußeren moralischen Staatlichkeit, die nun herangebildet werden soll in der nach römischen Formen gebauten römischen Papstkirche, die sich auswirken soll durch die Krönung der Könige zum römischen Kaiser, wodurch die Könige eingefaßt wurden in das Instrument der römischen Papstkirche, die selber nur heraus gemacht war aus dem ungöttlichen Romanismus. Ich spreche im christlichen Sinne, im Sinne der ersten Christenheit, die das Römische als den Feind empfand. Wie kommt man aus dem, was sich da vorbereitet, heraus? Herauskommen wollte man zuerst auf die Art, wie es der verinnerlichte Christ nicht zugeben konnte, durch die Verstaatlichung der Moralität, wie sie sich in der römischen Papstkirche herausgebildet hatte. Die Verstaatlichung, die äußerliche staatliche Verwaltung der Moralität ist dasjenige, was Augustinus auf der einen Seite noch angenommen hat, während es aber in den Tiefen seiner Seele Kräfte gab, durch die er sich auflehnte dagegen.

[ 18 ] Und wir sehen dann diese Auflehnung, man möchte sagen, dieses Sichhinneigen zu dem Moralischen, um wenigstens im Moralischen das Göttliche zu retten, nachdem man es im äußerlichen Weltlichen verloren hatte, wir sehen dieses Sichhinwenden zum Moralischen, wie es auftritt in dem Aufsuchen des «Fünkleins» bei Meister Eckhart, bei Tauler, bei Suso und so weiter, wie es insbesondere so tief innig auftritt in dem Büchlein «Theologia Deutsch». Das, meine lieben Freunde, ist der Kampf um die Moral, der jetzt auftritt, aus der man das Göttlich-Geistige nicht verlieren will, wenn es schon aus der äußeren Welterkenntnis und Weltverwaltung verloren wird. Aber man war lange Zeit eben nicht soweit, mit solcher Gewalt wie dann etwa Suso zum Moralischen und zum Ergreifen des Göttlichen im Moralischen vorzudringen.

[ 19 ] Zuerst handelte es sich darum, daß man in einer Art verschwommener Gestalt das Ganze regelte, daß man auf die Seite der Außenwelt hinblickend sich immer vorstellte, es müsse doch so etwas geben können wie einen Carolus magnus, der auf der einen Seite ein weltlicher Verwalter ist, und dem auch noch die staatliche Verwaltung des Moralischen mit der Kaiserkrone übertragen werden könnte für das Äußere, während die Kirche hinter ihm wirkte. Man stellte sich das so vor, und man bekam, ich möchte sagen, eine Art Gewissensnot, eine Gewissensnot, die historisch geworden ist. Dies begann im 9., 10. Jahrhundert, und diese innere Gewissensnot führte dann dazu, daß man hinblickte auf die Welt, und daß man, indem man mitten darinnenstand in dem Suchen des Göttlichen in dem Moralischen, aber doch nicht herauskam aus der Welt und in der Welt die Feinde suchte, [die man im Innern fühlte]. Man sah hin in die Welt, wenn man die Feinde suchen wollte. Das führte die Christen in die Gefahr, den Feind in der äußeren [Welt] zu suchen, das führte, meine lieben Freunde, zur Kreuzzugsstimmung.

[ 20 ] Die Kreuzzugsstimmung steht mitten drinnen in dem Streben, sich zu verinnerlichen, aber man kam doch nicht bis zu derjenigen Stätte im Innern, wo im Moralischen das Göttliche ergriffen wird. Die Kreuzzugsstimmung lebte in zwei Gestalten, sie lebte vor allen Dingen mit moralischem Einschlag bei Gottfried von Bouillon und seinen Genossen. In ihnen entstand der Ruf gegen Rom: Jerusalem contra Rom! Nach Jerusalem! Wir wollen Jerusalem an die Stelle von Rom setzen, denn an Rom haben wir die Veräußerlichung kennengelernt, in Jerusalem werden wir vielleicht die Verinnerlichung finden, wenn wir an den heiligen Stätten das Mysterium von Golgatha in der Erinnerung wieder durchleben. - Und so entstand eben die Vorstellung in einem Gottfried von Bouillon, die wir uns so denken können, daß er den Feind im Innern fühlte, aber ihn doch im Äußeren suchte, in den Türken suchte. Das Streben, nach dem Innern kommen zu wollen, um den Herrscher der Welt zu finden, aber zu gleicher Zeit einen König von Jerusalem zu krönen, in alledem drückte sich die historische Stimmung des 10., 11., 12. Jahrhunderts aus. Das lebte in diesen Menschen. Versuchen Sie es nur einmal, sich sowohl in die weltlichen wie in die geistigen Gründe [der Kreuzzüge] hineinzuversetzen, Sie werden überall diese historische Stimmung finden.

[ 21 ] Das sah Rom. Rom fühlte wohl, da bereitet sich im Norden etwas vor: Jerusalem gegen Rom. In Rom fühlte man die Veräußerlichung, Rom war aber vorsichtig, Rom hatte schon seine Prophetien gehabt, war aber vorsichtig und voraussehend, und Rom sieht voraus, was man wollte: Jerusalem gegen Rom. So tat es eben dasjenige, was es immer in solchen Fällen tut, es führte auf seine Art selber aus, was zunächst die anderen ausführen wollten, und es ließ der Papst durch seine Kreaturen, durch Peter von Amiens und seine Genossen, den Kreuzzug predigen, um von Rom aus das auszuführen, was eigentlich gegen Rom gehen sollte. Lesen Sie die Geschichte mit Verständnis, nehmen Sie das als einen Impuls, dann werden Sie schen, daß schon die ersten Kreuzzüge in dieser ersten Etappe zerfallen in das, was Rom vorausgenommen hat und das, was zuerst angestrebt wurde durch Gottfried von Bouillon und seine Genossen.

[ 22 ] Und so sehen wir die historische Stimmung, die in äußeren Handlungen das Innere sucht, ich möchte sagen, wir können diese historische Stimmung ja geistig greifen, wenn wir nun herauswachsen sehen aus den Kreuzzügen so etwas wie den Templerorden, der nun schon wiederum weiter ist in diesem Verinnerlichen. Er trägt als ein Ergebnis der Kreuzzüge das Innerliche mit. Er nimmt nur die Dinge so, daß er weiß, man kommt doch eigentlich nicht zu einer Verinnerlichung, wenn man nicht zugleich das Äußere durchdringt, wenn man nicht, um das Moralische zu retten, den Feind im Äußeren sieht. So paradox es Ihnen erscheinen mag, meine lieben Freunde, dasjenige, was Gottfried von Bouillon äußerlich im Raum in den Türken gesehen hat, das ist wie Luthers Kampf auf der Wartburg mit seinem Teufel als einer inneren Macht. Nach innen ist dieser Kampf gestellt.

[ 23 ] Und sehen Sie sich dann alles dasjenige an, was über die damalige zivilisierte Welt wie in Programmen zunächst erscheint in solchen Leuten wie Johannes Valentin Andreä, Comenius, was in den böhmischen Brüdern lebt, dann werden Sie verstehen, wie in den späteren Jahrhunderten aus den Kreuzzügen heraus das Streben nach Verinnerlichung gegangen ist. Ich muß sagen, am meisten schien es mir immer an einer einzelnen Stelle symptomatisch abgebildet, wenn ich hingeschaut habe auf diesen einsamen Denker, der in Böhmen lebte und ein Zeitgenosse von Leibniz war, Franziskus Josephus von Hoditz und Wolframitz. Er hat zum ersten Male mit aller Klarheit — das weiß man nur heute nicht — abgeschält das Moralische von dem Juristischen. Überall in der früheren Schriftstellerei war in ganz römischem Geiste das Juristische mit dem Moralischen verbunden. Das, was auf religiöse Art in allen den Leuten lebte, das lebte sich in philosophischer Art in diesem Zeitgenossen des Leibniz aus. Er will philosophisch das Moralische rein hinstellen. Und wie Luther sich die innere Rechtfertigung verschaffen wollte, weil in seiner Zeit es nicht mehr möglich war, die Rechtfertigung durch die äußere Welt zu finden, so sah Franziskus Josephus von Hoditz und Wolframitz als einsamer Denker die Aufgabe: Wie rette ich rein begrifflich das Moralische heraus aus der Umzingelung und Umspannung [durch das Juristische] mit jenen armen philosophischen Begriffen, wie rette ich das rein Menschlich-Moralische? — Die Frage vertieft sich ihm nicht religiös, die Frage wird nicht einseitig intellektualistisch gestellt bei Hoditz-Wolframitz. Aber gerade dadurch, daß sie philosophisch gestellt wird, merkt man, wie er philosophisch ringt nach einer reinen Herausgestaltung des im Bewußtsein lebenden moralisch-substantiellen Inhaltes.

[ 24 ] Sie müssen schon, wenn sie diese Zeiten verstehen wollen, die zuletzt ja doch unsere Zeit begründet haben, in der die Menschen der Gegenwart mit all ihren Empfindungen drinnen leben — ohne davon zu wissen —, Sie müssen schon, meine lieben Freunde, durchaus hinschauen auf die tiefen Seelenkämpfe, die da durchgemacht worden sind, auch wenn der moderne Mensch, der fühlt, daß er es «so herrlich weit gebracht» hat, beim Zurückschauen auf diese Zeit der furchtbarsten menschlichen Seelenkämpfe darin nur eine Periode des Aberglaubens sieht.

[ 25 ] Und so, möchte ich sagen, entstand in der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Kampf um das Moralische. Was erlebt worden ist in diesem Kampfe, das weist hinein bis in die heutigen Tage, und es kann geistig dem religiösen Suchen, dem religiösen Verhalten aufgedrängt sein bis in Verirrungen hinein. Noch immer nicht ist der Ausgleich gefunden zwischen Pistis und Sophia, zwischen Pistis und Gnosis. Noch immer klafft dieser Abgrund, demgegenüber der Schreiber des Johannes-Evangeliums den unendlichen Mut hatte, sich darüber zu stellen und die Wahrheit dazwischen zu finden. Dieses Aufbieten der Kraft im Suchen des Moralischen, im Rettenwollen des Göttlichen, indem man es nur auf das Moralische anwandte, das empfanden in ihrer schlichten, tiefen, allerdings unvollkommenen Art jene süddeutschen religiösen Leute, die heute nur als Sektierer angesehen werden, die Theosophen, die wir ja einerseits in Bengel, andererseits in Oetinger finden, die aber viel zahlreicher waren als diese zwei, und die mit aller Macht danach strebten, völlig ernst zu nehmen die Erringung des Göttlichen im Moralischen, die aber gerade, indem sie die Erringung des Göttlichen im Moralischen suchen, darauf kommen: Wir brauchen eine Eschatologie, wir brauchen eine Prophetie, wir brauchen ein Vorausschauen im Weltengang. Daher das noch Unvollkommene im Streben dieser Theosophen von der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, vom Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, in denen wir das Morgenrot sehen müssen von demjenigen, was dann neuerdings völlig verschüttet worden ist am Ende des 19.Jahrhunderts und im Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts, und was von allen denjenigen, die die Notwendigkeit einer religiösen Erneuerung empfinden, eben durchschaut werden muß.

[ 26 ] Aus dem Grunde können meine Antworten auf Ihre Wünsche, die aus dem Streben nach einer solchen religiösen Erneuerung kommen, nicht anders ausfallen, als sie eben ausfallen. Ich möchte schon durchaus Ihnen das geben, von dem ich glauben muß, daß Sie es in Wirklichkeit suchen.

Fourteenth Lecture