Foundation Course

Spiritual Discernment, Religious Feeling, Sacramental Action

GA 343

30 September 1921 a.m., Dornach

VIII. Prayer and Symbolism

[ 1 ] My dear friends! It is important that the question which we had yesterday and actually have been considering during the past days from the side of Anthroposophy, we now approach from a religious side, but again I don't want to do it through definitions and explanations but in a more concrete way. It is important in fact, as you have probably already sensed, to find a way which must come out of religious experience. What belong to religious experiences are the reality of prayer and the reality of the examination of the word, first becoming visible for us in the examining of Gospel words. We will have to draw on the more inner elements of religious life, but we will adhere to these two, prayer and the examination of Gospel words, through examples that are far better than concepts.

[ 2 ] Regarding prayer, my dear friends, one can from a religious standpoint say that a person who does not pray in our present time, cannot be a religious person. Certainly such a statement can be doubted from this point of view, but we don't want to enter into an abstract discussion but approach from a positive point of view, and this must always have some or other basis. So I would like to start from a kind of religious axiom, which for many can consist in feeling that without the possibility of praying it is not an inner religious experience, because in prayer a real union with the Divine must be sought, which interweaves and rules the world. It is important now to examine prayer.

We need to be clear that despite the general human differentiation in humanity, the care of a spiritual life also appears, according to the varied callings of different people. If prayer is also certainly something general and human, one can say that a special prayer is then again necessary for those who want to be teachers in the field of religious life, and this will bring us to the Breviary absolving. We want to speak about all these things because they are for you, namely young theologians, of imminent seriousness for the tasks that you are to set yourself, I'm not saying now, but which you can set yourself according to the demands of the time.

[ 3 ] Regarding prayer, in order to reach clarity, I want to speak about the Lord's Prayer and inner experiences of the Our Father. It is important that we may not take our starting point today from experiences of ancient Christianity by examining the Lord's Prayer or bringing it to life inwardly; our basis must be about contemporary man, because we want to speak about the Lord's Prayer in a general human way. Yet one must be aware of the following. Let's accept we will start to say the Lord's Prayer according to the style in which we say the first sentence: "Our Father who art in Heaven." It is important what we feel and experience in such a sentence and what we can feel and experience with other sentences of the Lord's Prayer, for only then will this prayer become inwardly alive. What we are talking about here, in fact, first of all, is to have something like an inner perception of such a sentence, not really just something that appears in the symbols of the words, but something that lives in us in real words. The heaven is basically the entire cosmos and we make it perceptible when we say "Our Father in Heaven" or "Our Father who art in the Heavens" or "Our Father, You are in the Heavens," so that in saying these words they are permeated with the spirit; we are turning towards the spirit. This is the perception of what we need to visualize, when we say such a sentence as "Our Father in the Heavens." Such a similar experience is what we need with the words "Your kingdom come," because within us there needs to be, more or less as an intuitive feeling, the question: What is this kingdom? If we are Christians, we will gradually, in our striving, approach a perception of this kingdom—or expressed more appropriately, the kingdoms—and be reminded of what was mentioned yesterday, we are reminded of Christ's words which sound and ends in "the kingdoms of heaven." Already in the 13th chapter of Matthew's Gospel, the Christ wants to speak to the people on the one hand and to the disciples on the other, about what the kingdom of heaven is. There has to be something lively about the phrase "Your kingdom" or "May Your kingdom come to us." When will the right thing come to life in us? The right thing will only become alive in us when we take such a sentence not as a thought, but when we make it alive as if we actually hear it within us, as if we apply what I have more than once spoken to you about recently. A path must be made from the concept to the word, because there is quite a different kind of inner experience when we, without outwardly saying the words, inwardly not only hold an abstract concept, but a lively experience of the sound, in whatever language it might be.

The entire Lord's Prayer becomes, so to speak, reduced out of the specificity of language, also when we in some or other language not only imagine the thought content but what is contained in the sound. This was stressed much more in earlier times regarding prayer, that the sound element becomes inwardly alive, because by the sound content becoming alive within, the prayer is transformed into what it should be, as an interactive conversation with the Divine. Prayer is never true prayer unless there is an exchange with the Divine, and for such an interactive conversation with the Divine, the Lord's Prayer is suited in the most immanent form because of its structure. We are so to speak outside of ourselves when we speak such sentences as "Our Father who art in the Heavens" or "Let Your kingdom come." We forget ourselves the moment we really make these sentences audible and alive within us. In these sentences we erase ourselves to a large extent simply by the content of the sentences, but we take hold of ourselves again when we read sentences of a different structure or make them inwardly alive. We take hold of ourselves again when we say: "hallowed be Your name." It is then actually a lively exchange with the Divine, because it transforms itself immediately as an inner deed in "hallowed be Your name."

On the one hand we have the perception that in "Our Father who art in Heaven" nothing is happening unless the sentence is thoroughly experienced. By us directing ourselves to inner listening, it enlivens our inner hearing for the name of Christ, like it did in pre-Christian times when the Jahve name had caused it, in the sense of what I had mentioned earlier about the beginning of the St John's Gospel. If we utter the sentence "Our Father who art in Heaven" within us in the right way in our time, then Christ's name mingles into this expression, then we inwardly give the answer to what we experience as a question: "Let this name be sanctified through us/ be hallowed by your name."

[ 4 ] You see, it takes prayer to live correctly into the Lord's Prayer; it takes on the form of an exchange with the Divine, even so when we in the right way experience the perception "Your kingdom come." This kingdom can't primarily be taken up in the intellectual consciousness; we can only take it up in the will. Similarly, when we lose ourselves with the sentence "Your kingdom come to us" we discover, taking hold of ourselves, that the kingdom, when it comes, works in us, that the actual Divine will happens in the heavenly kingdoms, and therefore also where we are on earth. You see, you have an exchange with the godhead in the Lord's Prayer.

[ 5 ] This conversational exchange prepares you firstly to have inner dignity in relation to the concerns the earth, and to bring it into a relationship with what has happened in this exchange, by connecting that to earthly relationships. Obviously to some of you it might appear that when I say "Hallowed by Your name" there's an enlivening of the Christ name. However, my dear friends, it is precisely here where the Christ Mystery lives. This Christ Mystery will not really be recognised for as long as St John's Gospel is not really understood. At the start of St John's Gospel, you read the words: "All things came into being through the Word and nothing of all that has come into being was made except through the Word." By ascribing the creation of the world to the Father God, you go against St John's Gospel. In the St John's Gospel you hold on to what you take as sure, that everything which exists as the world had been created through the word, thus in the Christian sense through the Christ, through the Son which the Father had substantially created, had subsisted, and that the Father has no name but that His name is actually that which lives in Christ. The entire Christ Mystery lives in these words: "Hallowed be your name" because the name of the Father is given in the Christ. We will still speak about this enough on other occasions, but I wanted to refer to it today, how in prayer a real inner conversational exchange with the Divine should be contained in the prayer itself.

[ 6 ] Now we can go further and say: Nothing is given to us from the natural world merely by taking our daily food, our bread. We take our bread from nature with the conditions which I've mentioned; by our digestive processes, through regenerative processes we become earthly man on the earth, but that can't really live in us because life in God is different, the life of God lives in the spiritual world. After we have entered into a conversation with the Divine in the first part of the Lord's Prayer, we can now out of this mindset which has permeated us within, release the negative and say positively: "You give us our bread, which works in our everyday life, today." With this it means: what has been nature's processes and work in us as processes of nature, this is what should, through our consciousness, through our inner experience, become a spiritual process. In this way our mindset should be transformed. We should become capable of forgiveness towards those who have done something to us, who have caused damage. We would only be able to do this when we become conscious of how much we have damaged the Divine spiritual, and therefore should ask for the right mindset in order for us to handle what we have become guilty of, in the right way; we can only do this if we have become aware that we are continuously doing harm to the Divine through the mere nature of our being, and continuously need the forgiveness of those beings towards whom we have become guilty.

[ 7 ] Now we can add the following, which is again an earthly thing, something which we want to link to the first thing we have related to: "Lead us not into temptation," which means: Let our connection to You be so alive that we may not experience the challenge to merge with mere nature, to surrender ourselves to mere nature, that we hold you firmly in all our daily nourishment. "But deliver us, from the evil." The evil consists of mankind letting go of the Divine; we ask that we are freed and let loose from this evil.

[ 8 ] When we ever and again have such experiences of the Lord's Prayer as our foundation, my dear friends, then we deepen the Lord's Prayer actively towards an inner life, which enables us to create the mood and possibility in us which allows us not only to act from one physical human to another physical human but that we act as one human soul to another human soul. In this way we have brought ourselves into a connection of the Divine creation in others, and we learn through this, what it is to experience such words as: "The least thing you have done to my brothers, you have also done to Me." In this way we have learnt to experience the Divine in the earthly existence. However we must in a real way, not through a theory, but in a real way turn away from worldly existence because we become aware that earthly existence, as it was first given to mankind, is actually no real worldly existence but an existence stripped of the Divine, and that we will only have a real worldly existence after we have turned ourselves to God in prayer, having created a link to God in our prayer.

[ 9 ] With this, my dear friends, the most elementary steps, the stairway, can lead to the conscious awakening of religious impulses in human beings. These religious impulses had to a certain extent been instilled in the human beings since primordial beginnings, but it concerns becoming aware of these impulses within, and that can only happen when a real exchange with the Divine in prayer comes about. The first meaningful discovery which one can make about the Lord's Prayer is that within its inner structure lies the possibility for a person to directly, with understanding, enter into a conversational exchange with the Divine. That is only a beginning, my dear friends, but it is so, however, that in the beginning, when it is really lived through, it is taken further and just when the question is taken religiously, it concerns wanting to find in our experience of the first steps, the strength to continue with the next steps through our own inner being.

[ 10 ] It is quite different to speak from the point of view of knowledge than it is to speak from the religious viewpoint. When one speaks from the side of knowledge, one deals mainly with the content; when one speaks about Anthroposophy as a religious element, my dear friends, then we need to pay attention to Goethe's words: Not What we think, but more How we think!—and for this reason I said yesterday, Anthroposophy inevitably, as is its character, leads to a religious experience, it flows into a religious experience through the How, how its content is experienced. However, when one speaks from the religious angle, it is necessary now not to look first at What it is which lies in the spread ahead of us, but that one goes out from this How, one comes from the human subject, one has to illuminate this human subject.

When you have found the attitude of prayer, you can now go to the other side and find it in the reading of the Gospels as well. The meaning the Gospels have for religious development, we will of course still speak about. In any case, real Christians need to remain within inner childlike feelings today in order to understand the Gospels in a believable way, also without criticism. When as a theologian he applies criticism, he has to, because he comes from the Christian angle, be able to understand the Gospel without criticism. At least he must firstly become strong in his experiences of the Gospels, and then, armed with this strength, he only then applies criticism. That's actually the basic damage in Bible criticism and actually in the Gospel criticism of the 19th Century; people are not initially religiously strengthened before they apply criticism to the Gospels. As a result, they have arrived at a Gospel criticism which is nothing other than done in the modern scientific sense. Nothing is more clearly felt regarding this modern scientific sense, my dear friends, than the Gospel words of St Matthew 13, for in Matthew 13, I could say, the pivotal point of the whole chapter are words which encloses a mystery, and that perhaps in the entire evolution of Christianity it could never have been felt more deeply by religious people than today, when they come up against the world. It is in the words: He answered and said: for you it is possible, to understand the mystery of the Kingdom of Heaven, but for those, whom I've just mentioned, the people around, it is not so.—To this an actually deep puzzle is connected: To him who has it, more will be given ... but he, who does not have it, nothing will be given: what would have been given to him, the little he has, will be taken from him.—These are extraordinarily deep words. Perhaps nowhere else in the evolution of Christianity can these words of giving and taking be so deeply felt—when one can really feel in a religious way towards the world and people—how just today, science has taken over nature and in the widest circles gained ever more authority; accepted to take away everything which could give the possibility of being able to spiritually hear with his ears or see with his eyes. This is not what man is supposed to do, in the scientific sense. Spirit should be obliterated in the sense of science, in the mood of our modern times. When we speak in the same way as modern theology speaks to people who are raised in scientific terms, we take away that little which they could have in religious feeling. When we counter what is done in the Faculty of Philosophy with what is done in enlightened theology today, we remove the last bit of what is religious.

[ 11 ] This needs to be felt, experienced in deep profundity, because the mood of the time is such has made it necessary for theologians to eradicate the religious. It is very necessary that we listen in a lively way to these words of the Matthew Gospel. However, this leads us to the next question: How can we discover the truth content, the vital content of the Gospel in the right way? We must find the correct way so that we can find the truthfulness also in the details of the Gospel and with this truthfulness directly illuminate the content of our lives. You see, in the way I'm saying this, I'm formulating my words in a particular way. I'm thinking of Paul's' words "Not I but Christ in me" and see how it should be spoken now in relation to the understanding of the Gospels, and when the word is within the heart of truth: "Not I, but Christ in me," the Christ said, in order to align the people in the right direction: "I am the way, the truth and the life."—We may express the words of Paul, "Not I but Christ in me," and then we will approach the Gospel in a way which leads to the right way to access the truthfulness and through this find the vital content in the Gospels. We have to climb up to a certain level in order to bring to life Paul's words: "Not I, but Christ in me." We must try to ever and again let it be spoken out, when we want to understand the Gospel. My dear friends, if Christ had spoken in the theologians of the 19th Century, then quite a different theology would have resulted, than it did, because a different Gospel view would have resulted.

[ 12 ] Having indicated the first steps to experiencing it further and continuing with the Matthew 13 Gospel, I would like to say a bit more. I stress clearly that this is the start of something we need to continue within ourselves, and here I want to again call your attention to the words "Think what? Think more how!"

By taking the 13th chapter of St Matthew's Gospel as our example, we must understand the situation: as soon as we approach the Gospel, we must renounce intellectualism and find our way into the descriptive element. Let us go straight away into the descriptive element and let's look at the verses leading up to this, in the verses 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 of the 12th chapter. These indicate how Christ Jesus is addressed: "See, your mother and our brother stand outside and want to talk to you"—and how he lifts his hand and points to his disciple and says: "Behold, in those souls live my mother and my brothers."—We want to go even deeper into these words, but first we need to clarify the situation. What we bring with us through birth into this life, the feeling which one can in the profoundest sense refer to as a child-like feeling, or as a brotherly feeling, this which we receive through the utmost grace, this is what is referred to here. Immediately the transition can be made towards which the most important aspect of Christianity is to lead; that we learn to extend, as best we can, the child-like, the brotherliness, to those souls with whom we have a spiritual connection. Wrong, it would be completely wrong, to feel this is somehow negative, when it is felt that only in the very least would that which lies in the childlike and brotherly feeling would be loosened and put in the place which lies in the feelings to the disciples. This is not what it is about, but it is rather about the human feeling lain into mankind as brotherhood, firstly only found in nature, therefore in that which we are born into this world as our first grace, in the feelings to our parents, to those we are bound through blood. We place ourselves positively towards it, and what we find in it, we carry over by ensouling it, towards all those with whom we want to have a Christian connection and want to live in a Christian community.

[ 13 ] This is what comes over into the 13th chapter of the Matthew Gospel. With it we are immediately in a starting position. If we take the content from the 53rd to 58th verses of the St Matthew's 13th chapter of the Gospel, and lead it over to the following, then we find that the greatest importance is the Christ Jesus now returns to his hometown, and through the experience of being in his hometown, express the words which appear in the 57th line of the 13th chapter: He says: "A prophet is nowhere less accepted than in his hometown and in his own house." The 58th verse now continues with the line: "And he was not able to do many deeds of the spirit there, for the sake of their unbelief." When we understand this situation, we are immediately led to see how Christ Jesus stands amidst people who have not understood the words: "Behold, in those souls live my mother and my brothers."

They failed to understand these words; as the words were not understood in their time; they also don't lead the way to Christ Jesus. The way to Christ Jesus has to be looked for. At this point it is indicated in the Matthew Gospel which people would find the way and who would not be able to find it, but also, how it can be found. We really need to understand that for those who are unable to ensoul the feelings of blood relationships given through grace to mankind, would not be able to find the way; those who only want to be part of their fatherland and not part of God's land, will not be able to find their way to Christ Jesus. So we are placed between two concrete experiences in Matthew's Gospel, chapter 13, and out of this situation we must expect that in this 13th chapter of Matthew's Gospel the relationship between the folk and Christ Jesus is stated, and how Christ Jesus as such can be discovered again by the folk.

[ 14 ] Let's enter more deeply into this situation. Already in the first sentence we are drawn more intimately into the situation. It is important firstly, to be able to enter right into it. You are already standing in it if you take what leads up to it and away from it; it is important to stand completely within it: "On the day of Saturn Jesus left his home and sat down at the lake."—If this is read without a lively engagement and purpose, then the 13th chapter of Matthew's Gospel is not actually being read. First of all, what is happening there is on the day of the Sabbath, the day of Saturn. We will discover, my dear friends, that the enfolding of the liturgy is found throughout the year but it is not indifferent regarding how a priest applies the Gospel; we will see that the Gospels are placed in the course of the year in such a way that people can find a connection in the Gospel to what can be experienced in nature, otherwise you will not really give the words of the Gospels their correct inner power.

[ 15 ] We will still talk about the details of the year's liturgy, but we need to get closer to these things. If you look at it spiritually, the 13th chapter of Matthew's Gospel speaks about the end of the world, that means the earthly world, and it is clearly indicated that it will happen in the manner of the prophecy. In the 35th verse it says: "That it might be fulfilled, that which is spoken by the prophet, who says: I want to open my mouth in parables and speak about the mysteries of the world's primordial beginning."—Here in the 13th chapter the end of the world should be spoken about. Christ Jesus chose the Sabbath because earlier people turned to it when they wanted to understand the beginning of the world, to compare it to the truths about the end of the world. The reception of these words needed an inner peace, it is indicated directly by the time setting. The effort of the preceding days must have taken place for man must be in need of rest in order to understand what would be said in the 13th chapter of Matthew's Gospel. He goes out of his home because he has something to say which goes further out than what can be said at home; this is the immediate recovery of verses 53 to 58. At home he couldn't have said anything. The writer of the Gospel is aware of indicating this in conclusion. You can't get close to the Gospel if you don't have the precondition that every word of the Gospel carries weight; it can't be indicated outwardly, you must try to let it enter into your inner life.

"He sat down beside the lake." You only realize what it means to sit beside the lake, how we are led in the wide world of experiences, when you sit at a lake and you are led away from everything which binds you to the earth. With the sensation of airspace, we already have too much abstraction which escapes us. Of course, experiences in the air spaces of the spirit leads us away from what chains us to the earth, but as human beings there is firstly something which escapes us.

[ 16 ] We now have him sitting down beside the lake. Here he now gathers the folk, and speaks to them of the Kingdom of Heaven, in parables. The disciples start to understand that when Christ Jesus speaks to the people in the way in which he addressed the disciples, in the examination of the parables, then people would also be deprived of what they have, at least. He could give the people nothing if he gave them the solutions to the parables. So what does he have to do first of all? To start off with, he should not speak of a spiritual world content, but firstly speak about world content, spread out before the senses. He needs to speak about the grain seed, leading them through every possibility in the destiny of the kernel. He must lead them to the possibility that the seed can't develop roots, or only weak roots, or hardly any roots, and can be lamed by opposing forces to fully develop its roots.

[ 17 ] My dear friends, you need to understand that you must speak in this way to people, because people first need to become inwardly alive towards what is usually thoughtlessly passed by. Their souls need to be lit up for the observation of the outer world. The soul remains dead and un-kindled if what lies externally, is not stirred up in inner words. People go thoughtlessly and wordlessly through the world. They look at the seed, which wilts. They see the seed which bears fruit, but they don't connect their seeing in such a way that it becomes alive as an inner seeing, an inner hearing. Only when we have transformed the experience of outer world into an inner image, only then do we have what can become preparation. The soul needs to be kindled by the external, the soul needs to revive itself in the external world. If you speak only about the meaning of nature, then you will firstly be speaking to deaf soul ears and blind soul eyes, and you will also take away the least which people have. You only give them something when they understand that you are speaking to their soul, speaking to their soul in the same way as Christ Jesus could speak to the disciples, having enlivened their souls through their participation in his life. The soul needs to be stirred, made to come alive towards the outer world and only after this enlivening is accomplished can you speak to the souls regarding interpretations placed before them as parables of nature. In this sense you link people initially to natural processes and try to transform the natural processes into images. Enliven everything which you can experience around you, imbue it in a sunny way.

From the moment we wake up in the morning, to the evening when we bring ourselves to rest, we are surrounded by sunshine. As unprepared individuals we have at first no inkling of what surrounds us in sunlight, which floods around us. We see sunlight reflected on single items, we initially see colours mirrored, but whether this imbuing sunshine floods through us as human beings experiencing colour, particularly activated and enlivened, we have no inkling of. We simply find ourselves in light from waking to going to sleep, and then we turn in a moonlit night to the moon, with open human hearts, and see how it is surrounded by stars that accompany it, and now return to the first experience which we could have that when you look at the sun, just when it is most lively with its light flooding around you, your eyes become blinded. The intensity of sunlight is so strong that it could, without hesitation, change eyes into suns.

If I look at the moon, then the moon throws the sunlight back to me, it sends the light back in such a way that I can take it in. The dazzling sunlight takes away the discretion. This discretion only remains while I'm looking at moonlight. The rays of the sun have such a majestic intensity that they do not have to rob me of my discretion when I turn towards them. I can turn to them when they are given again by the moon. How can I make this into an inner experience? I may and can, as a human being, unite myself with what the moon returns to me; I may, when I place it as a symbol in front of myself, have something with which I can unite myself. I can, with what I encounter in the moonlight, make myself an image with which I can unite myself. In other words, I may make an image of the sun, which has presented itself through the moonlight, and that is the Host, which I may consume. However, there is something so intense, so majestically great, that I can't be allowed to expose it immediately.

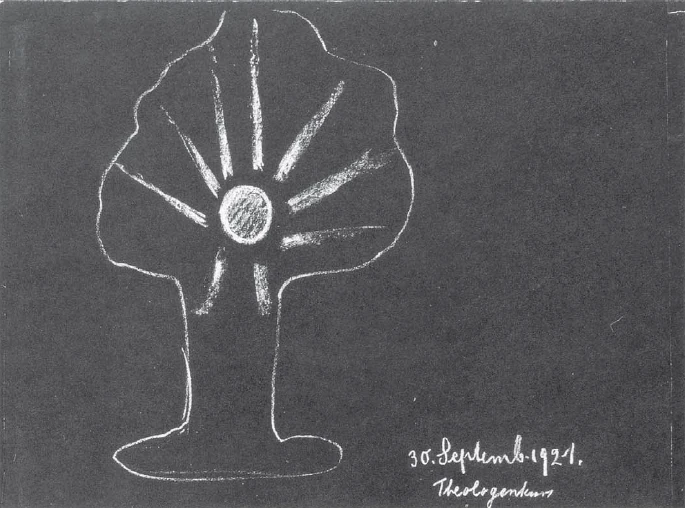

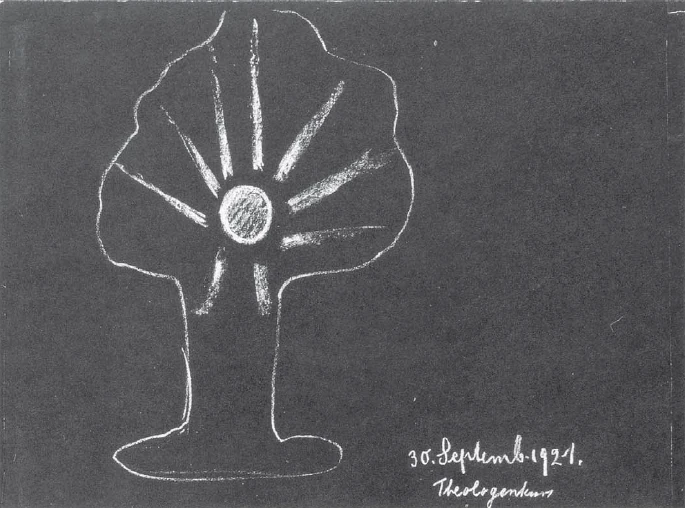

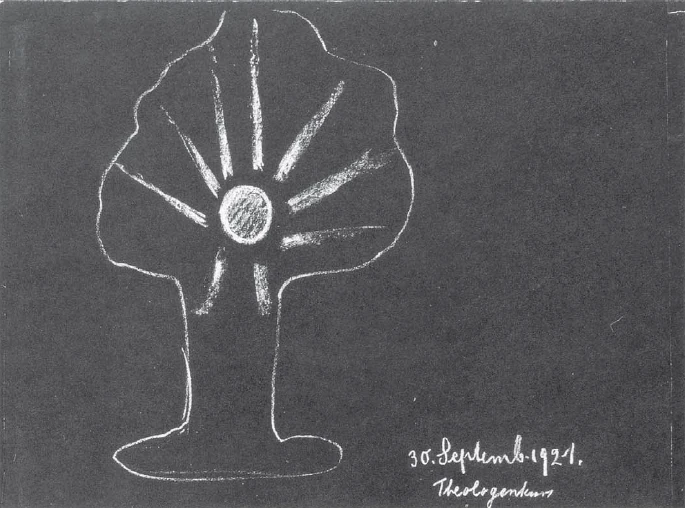

When I imagine this in images, I must present it in another way. I must determine a relationship which is not only visible as a similarity, and place it there, by becoming the nourishment for what the journey is allowed to become (the Host) surrounded with that which may only be looked at, with the monstrance (receptacle of the Host) [a drawing is done on the blackboard] and I have my relationship to the world born out of a dualistic comparison, a twofold kind, which I make into a kind of image with the inclusion of the monstrance. In the nourishment for the way, in the Host I have something with which I can unite. In what surrounds the Host I have an image of the weakened rays of the sun. Through communion there must appear in me what appears in the experience of the weakening, which I sense in moonlight, which I couldn't feel as a direct sun process, otherwise I would be blinded. In between both these is the communion: I place myself in the world context.

What the sun and moon have to say to one another, this is what is found in human beings, the human being stands right in it and enlivens it through communion.

[ 18 ] So you can see, further than just the mentioned comparison, it is distilled into a symbol which can be experienced. If it is experienced in the right sense, that means, experienced in a way as one does with others, with the full understanding of the words "And he pointed over to his disciple and said: See, that is my parent and my brother," then to a certain extent the human community is placed within the sense of these words, then one works towards community building and this teaching, how community building can be achieved, we will discover again when we move forward in the interpretation of Matthew 13.

[ 19 ] My dear friends, it is from inner knowledge—which an anthroposophical overview can give of human evolution—it is from my complete conviction that it would be especially bad for the present if we were to ignore the signs of the times today in order not to want to surrender to them. Just think, just when you allow your soul to look at Matthew's Gospel 13, you notice the following: the Catholic Church remains primarily fixed at the symbolism; what appeared in their community building was tied to the symbolism, the symbolism which lets you experience the kingdoms of the heavens. It didn't occur to anyone during the first centuries of Christianity's propagation, to speak about patience, that people could wait, and so on. I am obliged to say this. They were completely filled with the need for action, because they found the efficacy of symbolism and contribution of the symbol itself, as community building. They found within the symbolism what Christ wanted to indicate through the words which record the seven parables of the kingdom of God. They wanted through the symbolism make ears to hear and eyes to see before they started with the proclamation; you are standing within the living world of symbolism.

[ 20 ] Today we are standing in a completely changed time. We read in Matthew's 13 Chapter that initially explanations of the parables would only be given to the disciples. This we can't do today. It would be impossible today because the Gospels are in everyone's hands and the meaning of the parables can be read by everyone. We really live in a completely changed time. We don't really notice this at all. We must in a new way understand what the Matthew Gospel Chapter 13, contains. In the sense of our time, we must consider the structure of Matthew 13. Firstly, we have Christ sitting in front of the people, he delivers the parables to them about the kingdom of heaven, and from the 36th verse it is written: "Then Jesus left the people and came home, and his disciples approached him and said: Explain the parable of the weeds on the fields. And he explained it to them."

Let me clarify this situation completely. Firstly, the Christ speaks to the people in parables, which are clothed in outer events. He points to these parables for his disciples. He utters during these explanations meaningful words of mystery, which I have tried to bring closer to you. After he has returned home and spoke to his disciples about the parables of the weeds, he spoke to them about a number of other parables—about the treasure in the field, the priceless pearl, and some of the discarded fish found in the fishnet. Thus, he spoke about other parables to the disciples, after he had left the people. This all belongs to this situation: in the Gospels everything is important. We also have—let us place this clearly before our souls—the Christ at the lake, sitting in front of the people, telling them about the parables, then turning away, turning to the disciples, leading them into the situation in which he utters important mystery words, speaking to them alone away from the people, explaining the parables with the help of other parables, then, after he had again led them to the spirit-godly revelations, he asks if they had understood. Their answer is "Yes." Now the very next conclusion is—because everything else is just an introduction—: "Having been initiated into the scriptures you will conduct yourselves like a man who is master of his house, who takes out of his treasure that which he has experienced, but that part of what he has experienced which he has filled with life inwardly, so that he can add something new to it and then be able to present it to his listeners."

[ 21 ] I wanted to show you the way towards understanding Matthew 13, and tomorrow we will speak further about the content of truth and content of life, which can be found in this way in the Gospels. I have only indicated as an insertion how symbolism is found in this way in a central symbol from which certainly everything has to be believed, my dear friends, that it should also become a central symbolism for those who want to bring it into the ritual in pastoral care. What is needed is something visible as a symbol, which is more than just a product of nature, and for this, words are necessary which are enlivening; and action is necessary which is more than a mere action of nature. In the context of our civilization today we have dead words, not enlivened words. We only have actions, also human actions, which only contain nature's laws. We have neither living words, nor actions permeated by Divine will. To both of these we need to come through prayer and in reading the Gospels on the one hand and real fulfilling of the ritual on the other hand.

More about this tomorrow.

Achter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Meine lieben Freunde! Es handelt sich darum, der Frage, der wir gestern und eigentlich schon die vorigen Tage von der anthroposophischen Seite nähergetreten sind, nun von der religiösen Seite näherzutreten, und ich möchte das auch wiederum nicht in Definitionen und Erklärungen tun, sondern ich möchte mehr konkret den Weg andeuten. Es handelt sich ja tatsächlich dabei, wie Sie vielleicht schon gespürt haben werden, um einen Weg, der von den ganz charakteristischen Seiten des religiösen Erlebens ausgehen muß. Nun gehört zu dem religiösen Erleben die Realität des Gebetes und die Realität in der Vernehmung des Wortes, zunächst für uns anschaulich werdend in der Vernehmung des Evangelienwortes. Wir werden dann noch die mehr innerlichen Elemente des religiösen Lebens heranzuziehen haben, aber wir werden uns an diese beiden, an das Gebet und an die Vernehmung des Evangelienwortes, durch Beispiele, die besser sind als Begriffe, halten.

[ 2 ] Über das Gebet, meine lieben Freunde, kann man vom religiösen Standpunkte aus geradezu sagen: Wer nicht beten kann in unserer heutigen Zeit, kann kein religiöser Mensch sein. - Gewiß, so etwas kann angezweifelt werden von diesem oder jenem Standpunkt aus, aber wir wollen ja jetzt nicht abstrakte Diskussionen führen, sondern wir müssen von positiven Gesichtspunkten ausgehen, und die müssen immer in irgend etwas liegen. So möchte ich also ausgehen jetzt von einer Art religiösen Axioms, das eben für viele darin bestehen kann, daß man empfindet, ohne die Möglichkeit zu beten gibt es kein innerliches religiöses Erleben, denn im Gebete muß gesucht werden eine reale Vereinigung mit dem die Welt durchwebenden und durchwaltenden Göttlichen. Nun handelt es sich darum, wie wir zunächst an das Gebet herankommen. Da müssen wir uns klar sein, daß trotz alles Allgemein-Menschlichen Differenzierungen in der Menschheit auch in der Pflege des geistigen Lebens auftreten, je nach den Berufen, die die verschiedenen Menschen haben. Und wenn auch das Gebet durchaus etwas Allgemein-Menschliches ist, so kann man doch sagen, daß ein besonderes Beten wiederum notwendig ist für denjenigen, der auf dem Gebiete des religiösen Lebens als Lehrer auftreten muß, und das wird uns dann bringen zum Brevierabsolvieren. Über diese Dinge alle wollen wir ja sprechen, denn sie sind für Sie, namentlich für die jüngeren Theologen, von eminenter Wichtigkeit für die Aufgaben, die Sie sich, ich sage jetzt nicht, stellen sollen, sondern die Sie sich nach den Anforderungen der Zeit allein stellen können.

[ 3 ] Nun, für das Gebet möchte ich, um anschaulich sein zu können, an das Vaterunser selbst anknüpfen und möchte die innerliche Erlebensseite dieses Vaterunsers einmal hier besprechen. Es handelt sich dabei darum, daß wir vielleicht heute überhaupt von den Empfindungen gar nicht ausgehen können, die etwa das Urchristentum hatte beim Vernehmen oder beim Innerlich-Lebendigmachen des Vaterunsers; wir müssen von dem ausgehen, was der Mensch der Gegenwart haben kann, denn wir wollen vom Vaterunser als einem Allgemein-Menschlichen sprechen. Aber des folgenden muß man sich dabei doch bewußt sein. Nehmen wir also an, wir beginnen das Vaterunser zu sprechen und sprechen gewissermaßen in unserem Stil den ersten Satz «Vater unser in den Himmeln». Nun handelt es sich darum, was wir bei einem solchen Satz fühlen und empfinden, und was wir etwa bei anderen Sätzen des Vaterunsers fühlen und empfinden können, denn nur dadurch wird das Vaterunser innerlich lebendig. Da handelt es sich in der Tat darum, daß wir zunächst bei einem solchen Satz etwas haben wie ein innerliches Wahrnehmen, wirklich nicht bloß etwas, was im Zeichen des Wortes in uns lebt, sondern etwas, was im wirklichen Worte in uns lebt. Die Himmel sind im Grunde genommen die Gesamtheiten des Kosmos, und wir machen uns anschaulich, indem wir sagen «Vater unser in den Himmeln» oder «Vater unser, der Du bist in den Himmeln», daß dasjenige, zu dem wir da sprechen, von einem Geistigen durchdrungen ist, wir wenden uns an das Geistige. Das ist die Perzeption, das ist dasjenige, was wir uns so anschaulich wie möglich vor Augen bringen sollen, wenn wir einen solchen Satz aussprechen «Vater unser in den Himmeln». Ein ebensolches Erlebnis müssen wir haben [bei den Worten] «Dein Reich komme zu uns», denn in uns muß ja, wenn auch mehr oder weniger nur gefühlt und innerlich intuitiv, die Frage entstehen: Was ist nun dieses Reich? Und wenn wir Christen sind, werden wir gerade, indem wir versuchen, an die Perzeption des Reiches heranzukommen — oder besser gesagt: der Reiche -, erinnert werden an etwas, wovon gestern hier gesprochen worden ist, wir werden erinnert an Christus-Worte, die anklingen an den Terminus «die Reiche der Himmel». Gerade im 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums will ja der Christus sowohl zu dem Volke auf der einen Seite wie zu den Jüngern auf der anderen Seite darüber sprechen, was das Reich der Himmel ist. Es muß also etwas rege werden bei dem Satz «Dein Reich» oder «Deine Reiche mögen zu uns kommen». Nun, wann wird das Richtige rege in uns? Das Richtige wird in uns nur rege, wenn wir solche Sätze eben nicht als Gedanken haben, sondern wenn wir sie so lebendig machen können, als ob wir sie wirklich innerlich hörten, also wenn wir dasjenige anwenden, was ich in den letzten Tagen mehrfach mit Ihnen besprochen habe. Es muß der Weg gemacht werden vom Begriff zum Wort, denn es liegt darin ein ganz anderes innerliches Erleben, wenn wir, ohne daß wir äußerlich sprechen, innerlich nicht bloß einen abstrakten Begriffsinhalt haben, sondern das lebendige Erleben des Lautes, in welcher Sprache es zunächst auch sei. Das ganze Vaterunser wird gewissermaßen das Spezifische der Sprache schon hinwegreduzieren, auch wenn wir im einzelnen aus irgendeiner Sprache heraus nun nicht vorstellen den bloßen Gedankeninhalt, sondern den Lautinhalt. Auf das wurde nämlich gerade in früheren Zeiten beim Beten außerordentlich viel gehalten, daß der Lautinhalt innerlich lebendig wird, denn nur wenn der Lautinhalt innerlich lebendig wird, verwandelt sich das Gebet in dasjenige, was es sein muß, in ein Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen. Niemals ist das Gebet ein wirkliches Gebet, wenn es nicht ein Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen ist, und zu einem solchen Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen ist allerdings das Vaterunser im eminentesten Sinn gemacht durch seinen besonderen Bau. Wir sind gewissermaßen aus uns selbst heraus, indem wir solche Sätze sprechen wie «Vater unser, der Du bist in den Himmeln» oder «Deine Reiche mögen zu uns kommen». Wir vergessen uns in dem Augenblick selbst, indem wir richtig diese Sätze innerlich hörbar lebendig machen. Wir löschen uns bei diesen Sätzen in einem hohen Maße einfach durch den Inhalt der Sätze aus, aber wir nehmen uns wieder in die Hand, wenn wir Sätze anderer Struktur lesen oder innerlich lebendig machen. Wir nehmen uns sofort wiederum in die Hand, wenn wir sagen «Dein Name werde geheiliget». Es ist tatsächlich dann ein lebendiges Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen, denn es verwandelt sich sofort dieses «Dein Name werde geheiliget» in uns in die innere Tat. Wir haben auf der einen Seite die Perzeption «Vater unser, der du bist in den Himmeln»; ohne daß etwas dabei geschieht, ist es nicht möglich, diesen Satz in seiner Vollständigkeit zu erleben. Und indem wir uns auf das innerliche Hören einstellen, erregt dieses innerliche Hören in uns den Christus-Namen, wie es in vorchristlichen Zeiten den Jahve-Namen erregt hat, in dem Sinne, wie ich über den Anfang des Johannes-Evangeliums gesprochen habe. Sprechen wir also in uns selber den Satz «Vater unser, der Du bist in den Himmeln» in der richtigen Weise aus, dann mischt sich hinein in dieses Aussprechen für uns in unserer heutigen Zeit der Christus-Name, und dann geben wir innerlich die Antwort auf dasjenige, was wir als eine Frage empfinden: «Dieser Name werde durch uns geheiliget.»

[ 4 ] Sie sehen, es nimmt das Gebet dadurch, daß wir richtig uns hineinleben in das Vaterunser, die Form des Wechselgespräches mit dem Göttlichen an; ebenso, wenn wir in der richtigen Weise als Perzeption erleben «Deine Reiche mögen zu uns kommen». Diese Reiche können wir zunächst nicht in das intellektualistische Bewußtsein aufnehmen, wir können sie allein in den Willen aufnehmen. Und wiederum wenn wir in dem Satze «Deine Reiche mögen zu uns kommen» uns selbst verlieren, finden wir uns, nehmen wir uns in die Hand und geloben, daß die Reiche, wenn sie zu uns kommen, in uns wirken, daß wirklich der göttliche Wille geschehe wie in den himmlischen Reichen, also auch da, wo wir sind auf Erden. Sie sehen, Sie haben ein Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen in dem Vaterunser.

[ 5 ] Dieses Wechselgespräch bereitet Sie dann vor, überhaupt erst die innere Würdigkeit zu haben, um dasjenige, was nun der Erde angehört, mit demjenigen in Beziehung zu bringen, mit dem Sie in das Wechselgespräch gekommen sind, auch für die irdischen Verhältnisse. Auffällig könnte es einem erscheinen, daß ich sage, die Worte «Dein Name werde geheiligt» erregen in uns den Christus-Namen. Aber darin, meine lieben Freunde, liegt ja das ganze Christus-Geheimnis. Dieses Christus-Geheimnis wird solange nicht richtig gesehen werden, solange der Anfang des Johannes-Evangeliums nicht richtig verstanden wird. Am Anfang des Johannes-Evangeliums lesen Sie die Worte «Alles ist durch das Wort entstanden, und nichts gibt es in dem Entstandenen, was nicht durch das Wort entstanden wäre». Indem man dem Vater-Gott zuschreibt die Weltenschöpfung, vergeht man sich ja gegen das Johannes-Evangelium. An dem Johannes-Evangelium hält man nur fest, wenn man die Sicherheit darüber hat, daß dasjenige, was entstanden ist, dasjenige, was man als Welt um sich hat, durch das Wort entstanden ist, also im christlichen Sinne durch den Christus, durch den Sohn, daß der Vater das substantiell Zugrundeliegende, das Subsistierende ist, und daß der Vater keinen Namen hat, sondern daß sein Name eben dasjenige ist, was in dem Christus lebt. Es liegt das ganze Christus-Geheimnis in diesem «Dein Name werde geheiliget», denn der Name des Vaters ist in dem Christus gegeben. Wir werden darüber noch genug zu sprechen haben bei anderen Gelegenheiten, aber ich wollte heute vor allem darauf hinweisen, wie im Gebet ein reales inneres Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen schon durch den Inhalt des Gebetes da sein muß.

[ 6 ] Dann können wir weitergehen und uns sagen: Nicht ist uns von der bloßen Naturwelt dasjenige gegeben, was wir alltäglich werden durch die Aufnahme unserer Nahrung, durch das Brot. Wir nehmen das Brot von der Natur herein durch die Vorgänge, die ich Ihnen geschildert habe; durch unsere Verdauungsvorgänge, durch die Regenerationsvorgänge werden wir dasjenige, was wir auf Erden als Erdenmenschen sind, aber das darf nicht in uns wirklich leben, denn das Leben des Gottes ist anders, das Leben des Gottes lebt in dem geistigen Geschehen. Nachdem wir also in das Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen gekommen sind im ersten Teil des Vaterunsers, können wir nun, aus der Stimmung heraus, die dann unser Inneres ergriffen hat, das Negative weglassen und das Positive sagen: «Unser im Alltäglichen wirkendes Brot gib Du uns heute.» Damit ist ja gemeint: Das, was sonst nur Naturvorgänge sind und als Naturvorgänge in uns wirkt, das soll durch unser Bewußtsein, durch unser inneres Erleben ein Geistesvorgang werden. Und ebenso soll unsere Gesinnung verwandelt werden. Wir sollen fähig werden, denjenigen, die uns etwas getan haben, die uns etwas geschadet haben, zu vergeben. Wir können das nur, wenn wir uns bewußt werden, daß wir vieles geschadet haben an dem Göttlich-Geistigen, und daß wir deshalb zu bitten haben um die richtige Gesinnung, damit wir das, was uns auf der Erde geschadet hat, was an uns auf der Erde geschuldet worden ist, in der richtigen Weise behandeln können; wir können das nur, wenn wir uns bewußt werden, daß wir ja immerdar durch unser bloßes Natursein dem Göttlichen Schaden zufügen und fortdauernd die Vergebung desjenigen Wesens brauchen, dem wir da schuldig geworden sind.

[ 7 ] Und dann können wir ja auch das folgende vorbringen, was wiederum eine irdische Sache ist, also dasjenige, was wir hinaufsenden wollen zu dem, zu dem wir uns zuerst in ein Verhältnis gesetzt haben. «Führe uns nicht in Versuchung», das heißt: Lasse so rege sein in uns die Verbindung mit Dir, daß wir nicht die Anfechtung erfahren, in dem bloßen Natursein aufzugehen, uns bloß dem Natursein hinzugeben, daß wir Dich festhalten können in all unserer alltäglichen Nahrung. «Und befreie uns, erlöse uns von dem Übel.» Das Übel besteht darin, daß der Mensch sich loslöst von dem Göttlichen; wir bitten, daß wir befreit und erlöst werden von diesem Übel.

[ 8 ] Wenn wir, immer mehr und mehr von solchen Empfindungen ausgehend, an das Vaterunser herantreten, meine lieben Freunde, dann vertieft sich das Vaterunser in der Tat zu einem innerlichen Erleben, das uns fähig macht, wirklich uns durch die Stimmung, in die wir uns da versetzen, auch die Möglichkeit zu verschaffen, nicht bloß vom physischen Menschen zum physischen Menschen zu wirken, sondern als menschliche Seele zur menschlichen Seele. Denn wir haben ja dann uns selber gewissermaßen zum Anschluß gebracht an das Göttliche und finden die göttliche Schöpfung in dem anderen Menschen, und wir lernen dadurch erst empfinden, wie wir ein solches Wort aufzufassen haben: «Was ihr einem der geringsten Meiner Brüder getan habt, das habt ihr Mir getan». Da haben wir gelernt, das Göttliche zu empfinden in allem Irdisch-Daseienden. Aber wir müssen uns im realen Sinn, nicht durch eine Theorie, sondern im realen Sinn von dem Weltendasein wegwenden, weil wir gewahr werden, daß das Weltendasein, das uns als Menschen zuerst gegeben ist, gar nicht das wirkliche Weltendasein ist, sondern das entgöttlichte Weltendasein, und daß wir das wirkliche Weltendasein erst haben, nachdem wir uns im Gebet zu Gott gewendet haben und eine Verbindung zu Gott im Gebet gefunden haben.

[ 9 ] Damit, meine lieben Freunde, ist ja zunächst nur in elementarsten Stufen angedeutet die Treppe, die Stiege, die hinaufführen kann in das Bewußtwerden des religiösen Impulses im Menschen. Dieser religiöse Impuls ist ja gewissermaßen vom Urbeginne ab im Menschen gelegen, aber es handelt sich darum, daß sich der Mensch dieses in ihm liegenden Impulses bewußt wird, und er kann das nur, wenn das Gebet in ihm ein reales Wechselgespräch mit dem Göttlichen wird. Es ist die erste bedeutsame Entdeckung, die man beim Vaterunser machen kann, daß es durch seinen inneren Bau schon so ist, daß man durch es unmittelbar, wenn man es versteht, in ein wechselseitiges Verhältnis des Menschlichen mit dem Göttlichen kommen kann. Das ist allerdings nur ein Anfang, meine lieben Freunde, aber es ist so, daß der Anfang, wenn er richtig erlebt wird, von selbst weiterführt, und gerade, wenn die Frage religiös gefaßt wird, so handelt es sich darum, daß wir an dem Erleben der ersten Schritte die Kraft finden wollen, die folgenden Schritte durch unser eigenes Inneres zu machen.

[ 10 ] Es ist ganz anders, wenn man von der Erkenntnisseite aus spricht und wenn man von der religiösen Seite aus spricht. Wenn man von der Erkenntnisseite aus spricht, dann hat man es zunächst hauptsächlich mit dem Inhalt zu tun, und wenn man von Anthroposophie als einer religiösen Sache spricht, meine lieben Freunde, dann muß schon das Goethesche Wort durch und durch beachtet werden: Das Was bedenke, mehr bedenke Wie! -; und deshalb habe ich gestern zu Ihnen sagen können: Anthroposophie führt ganz unweigerlich durch ihren Charakter zu einem religiösen Erleben, sie mündet ein in ein religiöses Erleben durch das Wie, wie ihr Inhalt erlebt wird. Wenn man aber von der religiösen Seite her redet, hat man notwendig, nun nicht zunächst auf das hinzuschauen, was als das Was in Ausbreitung vor uns liegt, sondern man hat von diesem Wie auszugehen, man hat von dem menschlichen Subjekt auszugehen, man hat hineinzuleuchten in dieses menschliche Subjekt. Und jetzt handelt es sich darum, daß, wenn man die Stimmung des Gebetes gefunden hat, man die andere Seite, das Lesen des Evangeliums auch findet. Welche Bedeutung das Evangelium in der religiösen Entwickelung hat, davon wollen wir noch sprechen. Aber jedenfalls müßte ja dem wirklichen Christen heute noch das an ganz kindlicher inniger Empfindung geblieben sein, daß er zum Evangelium in einer gläubigen Weise greifen kann, auch ohne Kritik. Wenn er auch als Theologe die Kritik anwendet, er müßte, weil er sonst sich aus dem Christlichen herausstellt, zum Evangelium greifen können ohne Kritik. Mindestens müßte er sich zunächst in dem Erleben des Evangeliums so stark gemacht haben, daß er mit dieser Stärke ausgerüstet dann erst die Kritik anwendet. Das ist eigentlich der Grundschaden in der Bibel- und namentlich in der Evangelien-Kritik des 19. Jahrhunderts, daß die Menschen sich nicht zuerst religiös stark genug gemacht haben, bevor sie an die Evangelien-Kritik herangetreten sind. Dadurch sind sie dann bei der Evangelien-Kritik in diejenige Stimmung gekommen, die keine andere ist als die moderne Wissenschaftsstimmung. Aber vielleicht an nichts so sehr, meine lieben Freunde, wie an dieser modernen Wissenschaftsstimmung, erfüllt sich das Wort von Matthäus13, das in Matthäus 13, ich möchte sagen, der Angelpunkt des ganzen Kapitels ist, ein Wort, das, ich möchte sagen, ein Mysterium einschließt, und das vielleicht in der ganzen Zeit der Entwickelung des Christentums niemals so tief hat gefühlt werden können wie vom religiösen Menschen heute, wenn er sich der Welt gegenüberstellt. Es ist das Wort: Er antwortete und sprach: Euch kommt es zu, das Mysterium von den Reichen der Himmel zu verstehen, aber jenen, zu denen ich eben gesprochen habe, dem Volk ringsumher, denen kommt es nicht zu. — Daran knüpft sich jetzt das eigentliche tiefe Rätselwort: Denn derjenige, der da hat, dem darf gegeben werden, wer aber nicht hat, dem darf nicht gegeben werden; dem würde, wenn man ihm gäbe, auch das Wenige noch genommen, was er hat. — Das ist ein außerordentlich tiefes Wort. Und vielleicht wirklich niemals in der Entwickelung des Christentums konnte man dieses Wort vom Geben und Nehmen so tief fühlen - wenn man wirklich religiös fühlen kann gegenüber Welt und Mensch — wie gerade heute, wo eine Wissenschaft über die Natur populär und für weiteste Kreise immer mehr und mehr Autorität geworden ist, welche geeignet ist, dem Menschen alles dasjenige zu nehmen, was er an Möglichkeiten hat, das Geistige mit den Ohren zu hören und mit den Augen zu sehen. Denn das soll er nicht, im Sinne dieser Naturwissenschaft. Der Geist soll getilgt werden im Sinne dieser Naturwissenschaft, im Sinne dieser unserer heutigen Zeit. Wenn wir so sprechen, wie die moderne Theologie spricht zu diesen Menschen, die in naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffen aufgezogen sind, nehmen wir ihnen noch das Wenige, was sie haben an religiösem Fühlen. Indem wir demjenigen, was an der philosophischen Fakultät getrieben wird, entgegenhalten das, was heute von der aufgeklärten Theologie getrieben wird, nehmen wir noch das letzte Religiöse hinweg.

[ 11 ] Das muß in voller Tiefe heute gefühlt, empfunden werden, wo Theologen, weil die Zeitsimmung eben diejenige ist, die sie notwendig werden mußte, das Religiöse vielfach gerade durch die Theologie austilgen. Wir hätten sehr nötig, gerade heute auf diese Worte des Matthäus-Evangeliums lebendig hinzuhorchen. Das aber führt uns dazu zu fragen: Wie können wir überhaupt den Wahrheitsgehalt, den Lebensgehalt des Evangeliums finden durch einen rechten Weg? Wir müssen den rechten Weg suchen, damit wir den Wahrheitsgehalt auch im einzelnen des Evangeliums finden und damit dieser Wahrheitsgehalt in uns unmittelbar aufleuchtet als Lebensgehalt. Sehen Sie, indem ich dies sage, formuliere ich meine Worte in einer ganz bestimmten Weise. Ich gedenke da des PaulusWortes «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir» und prüfe, wie nun gesprochen werden müßte mit Bezug auf das Ergreifen des Evangeliums, wenn das Wort im Herzen die Wahrheit ist: «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir», [der Christus,] der sagt, um den Menschen in die rechte Richtung zu bringen: «Ich bin der Weg, die Wahrheit und das Leben.» — Wir dürfen nur das Paulus-Wort sprechen «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir», dann werden wir uns dem Evangelium so nähern, daß wir den rechten Weg zum Wahrheitsgehalt und dadurch zum Lebensgehalt im Evangelium finden. Wir müssen uns hinaufranken dazu, in einer gewissen Weise lebendig zu machen das Paulus-Wort «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir». Wir müssen versuchen, Ihn immer sprechen zu lassen, wenn wir das Evangelium verstehen wollen. Und hätte, meine lieben Freunde, der Christus in den Theologen des 19. Jahrhunderts gesprochen, es wäre eine andere Theologie zustandegekommen, als sie zustandegekommen ist, weil eine andere Evangelien-Auffassung zustandegekommen wäre.

[ 12 ] Und nun möchte ich, indem ich die ersten Schritte andeute, daran erlebend immer weiter und weiterführend über dieses 13. MatthäusEvangelium-Kapitel einiges zu Ihnen sprechen. Ich betone ausdrücklich, es ist der Anfang desjenigen, was wir dann im eigenen Innern weiterführen müssen, und da möchte ich Sie wiederum aufmerksam machen auf das Wort «Das Was bedenke, mehr bedenke Wiel». Indem wir das 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums vornehmen, müssen wir uns versetzen in die Situation; denn sogleich, indem wir an das Evangelium herantreten, müssen wir verzichten auf den Intellektualismus und uns in das Anschauliche hineinfinden. Gehen wir gleich an das Anschauliche heran und sagen wir uns die vorangehenden Sätze 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 des 12. Kapitels. Diese weisen uns darauf hin, wie zu dem Christus-Jesus gesprochen wird: Siehe, Deine Mutter und Deine Brüder stehen draußen und wollen mit Dir reden —, und wie er die Hand hebt und hinweist auf seine Jünger und sagt: Siehe, in deren Seelen leben meine Mutter und meine Brüder. - Wir wollen auf das Wort noch näher eingehen, aber zunächst haben wir uns diese Situation klarzumachen. Dasjenige, was in der Empfindung liegt, die man mitbringt durch die Geburt ins Leben, die man bezeichnen kann im allertiefsten Sinne als das kindliche Gefühl und als das brüderliche Gefühl, das also, was uns durch die allererste Gnade wird, das ist es, worauf hier hingewiesen wird. Und sogleich wird der Übergang gemacht zu einem Allerwichtigsten, wozu das Christentum führen soll: daß wir das Beste, das wir erfühlen können an diesem Kindlichen und an diesem Brüderlichen, ausdehnen lernen über diejenigen, mit denen wir im Geiste in der Seele verbunden sind. Falsch, durchaus falsch wäre es, wenn dies etwa als ein Negatives gefühlt würde, wenn gefühlt würde, daß nur im allergeringsten dasjenige gelockert würde, was im kindlichen und brüderlichen Gefühl liegt, und an diese Stelle das gesetzt würde, was in dem Gefühl zu den Jüngern liegt. Darum handelt es sich ganz gewiß nicht, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß das, was dem Menschen hineingelegt ist in das Gefühl zu seinen Brüdern, zunächst im Naturgemäßen gefunden wird, also in demjenigen, was für uns als die erste Gnade mit uns in die Welt hereingeboren wird, in dem Gefühl zu den Eltern, zu denen, die uns blutsverwandt sind. Positiv stellen wir uns dazu, und was wir darin finden können, das übertragen wir, indem wir es verseeligen, auf alle diejenigen, mit denen wir christlich verbunden sein wollen und in christlicher Gemeinschaft leben wollen.

[ 13 ] Das ist es, was hinüberleitet zum 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums. Wir stehen damit sogleich in der Anfangssituation darinnen. Und nehmen wir nun das, was als 53. bis 58. Satz dieses 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums beschließt und was dann hinüberleitet zu dem folgenden, dann finden wir, daß das Wichtigste daran ist, daß der Christus-Jesus jetzt zurückkehrt in seine Vaterstadt und durch die Erfahrungen in seiner Vaterstadt genötigt ist, das Wort auszusprechen, das im 57. Satz des 13. Kapitels steht: «Ein Prophet gilt nirgends weniger, denn in seinem Vaterlande und in seinem Hause», und daß sich daran der 58. Satz des 13. Kapitels reiht: «Und er tat daselbst nicht viele Zeichen um ihres Unglaubens willen.» Wir werden, wenn wir die Situation erfassen, sofort dahin geführt, zu sehen, der Christus-Jesus steht inmitten von solchen Leuten, die nicht das Wort begriffen haben «Siehe, das sind meine Eltern und das sind meine Brüder». Sie haben diese Worte nicht verstanden; und weil sie die Worte nicht verstehen wollen in ihrer Zeit, finden sie auch nicht den Weg zu dem Christus-Jesus. Der Weg zu dem Christus-Jesus soll gesucht werden. Gezeigt wird uns an dieser Stelle des Matthäus-Evangeliums, welche Menschen den Weg finden, und welche ihn nicht finden können, damit aber auch, wie er gefunden werden kann. Nur müssen wir verstehen, daß diejenigen, die nicht das Gefühl der Blutsverwandtschaft, das als erste Gnade dem Menschen mitgegeben ist, versceligen können, den Weg nicht finden, daß von ihnen, die an dem bloßen Vaterlande und nicht an dem Gotteslande teilhaben wollen, der Weg zu dem Christus-Jesus nicht gefunden werden kann. So wird uns das 13. Kapitel des MatthäusEvangeliums zwischen ganz konkrete Erlebnisse hineingestellt, und wir müssen nun einfach aus der Situation heraus erwarten, daß uns in diesem 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums eben gerade dargelegt wird das Verhältnis des Volkes zu dem Christus-Jesus, wie der Christus-Jesus als solcher von dem Volke gefunden werden kann.

[ 14 ] Gehen wir noch näher auf diese Situation ein. Gleich der erste Satz führt uns intimer in die Situation hinein. Es handelt sich zuerst darum, ganz darinnenstehen zu können. Man steht schon etwas darin, wenn man die Zu- und die Ausleitung nimmt; es handelt sich um das völlige Darinnenstehen: An dem Saturnustage ging Jesus aus seinem Heim hinweg und setzte sich ans Meer. - Ohne daß man das als eine lebendige Begebenheit und eine Bestimmung empfindet, liest man das 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums ja nicht, Erstens ist das, was da geschieht, am Sabbatstage, am Saturntage geschehen. Wir werden sehen, meine lieben Freunde, daß uns die Entfaltung der Liturgie durch das Jahr hindurchführen wird, und daß es gar nicht gleichgülug ist, wie man in der Seelsorge das Evangelium verwendet; wir werden sehen, daß man das Evangelium in das Jahr hineinzustellen hat, daß man anzuknüpfen haben wird mit dem Evangelium an dasjenige, was in der Natur erfahren werden kann, sonst wird man den Worten des Evangeliums doch nicht die rechte innere Kraft geben. Über die Einzelheiten der Jahresliturgie werden wir noch zu sprechen haben, aber wir müssen uns diesen Dingen einmal nähern.

[ 15 ] Es wird, wenn man das vergeistigt ansieht, im 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums vom Ende der Welt, das heißt der Erdenwelten gesprochen, und es wird ja deutlich darauf hingedeutet, daß das im Sinne der Prophetie geschieht. Im 35.Satz heißt es: «Auf daß erfüllet würde, was gesagt worden ist durch den Propheten, der da spricht: Ich will meinen Mund auftuen in Gleichnissen und will aussprechen die Mysterien vom Urbeginne der Welt.» — Hier im 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums soll ja hauptsächlich über das Ende der Welt gesprochen werden. Der Christus-Jesus wählt den Sabbat, an den man sich früher gewendet hat, wenn es sich darum handelte, den Anfang der Welt zu begreifen, um die Wahrheiten vom Ende der Welt dem entgegenzusetzen. Daß es der innerlichen Ruhe bedarf, das wird ja sogleich angedeutet durch die Zeitbestimmung. Die Mühe der vorhergehenden Tage muß vorangegangen sein, der Mensch muß der Ruhe bedürftig sein, dann kann er verstehen, was ihm im 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums gesagt werden soll. Er ging aus seinem Hause fort, weil er etwas zu sagen hat, was in die Weiten geht, was nicht im Hause gesagt werden konnte; das zeigt sogleich die Ausleitung, der 53. bis 58.Satz. Zu Hause hätte er es gar nicht sagen können. Das ist der Schreiber des Evangeliums genötigt, am Schluß anzudeuten. Man kommt nicht heran an das Evangelium, wenn man nicht die Voraussetzung hat, daß jedes Wort im Evangelium abgewogen ist; man darf es nicht äußerlich deuten, man muß versuchen, in sein inneres Leben einzudringen. «Und er setzte sich ans Meer.» Man vergegenwärtige sich nur, was es heißt, am Meere zu sitzen, wie wir in die Weiten der Weltempfindung geführt werden, wenn wir am Meere sitzen, wie wir da hinweggeleitet werden von allem, was uns an die Erde fesselt. An der Empfindung des Luftraumes haben wir schon ein viel zu Abstraktes; das entschlüpft uns. Es würden uns ja natürlich die Erlebnisse des Luftraumes im Geistigen hinwegführen von dem, was uns auf Erden kettet, aber wir haben als Menschen natürlich darin etwas, das uns zunächst eigentlich entschlüpft.

[ 16 ] Wir haben also das Sichsetzen an das Meer. Und da versammelte er nun das Volk, und dem Volke sprach er von den Reichen der Himmel in Gleichnissen. Und seinen Jüngern wird begreiflich, daß, wenn der Christus-Jesus zu dem Volke so spräche, wie er sprechen kann zu den Jüngern in der Auseinandersetzung der Gleichnisse, dann den Leuten auch das noch genommen würde, was sie an Wenigem haben. Er würde ihnen gar nichts geben können, den Leuten, wenn er ihnen die Auslegung der Gleichnisse böte. Was muß er denn zuerst tun? Er muß zuerst nicht sprechen von einem geistigen Welteninhalt, sondern er muß zuerst sprechen von dem Welteninhalt, der zunächst sich vor den Sinnen ausbreitet. Er muß sprechen von dem Samenkorn, und er muß führen zu all den Möglichkeiten, die das Schicksal des Samenkornes sein können. Er muß führen zu der Möglichkeit, daß das Samenkorn gar nicht Wurzel fassen könne, daß es nur schwach Wurzel fassen könne, daß es zwar Wurzel fassen könne, aber durch entgegengesetzte Kräfte wiederum gelähmt wird, um völlig Wurzel fassen zu können.

[ 17 ] Meine lieben Freunde, Sie werden damit rechnen müssen, daß man in solcher Weise zum Volke sprechen muß, weil das Volk erst innerlich dasjenige lebendig bekommen muß, was es eigentlich gedankenlos überschaut. Man muß die Seele erst entzünden an einem Anschauen des Äußerlichen. Die Seele bleibt tot und unentzünder, wenn man in ihr nicht rege macht im innerlichen Worte dasjenige, was äußerlich daliegt. Die Menschen gehen gedanken- und wortlos durch die Welt, Sie sehen das Samenkorn, das verwelkt, sie sehen das Samenkorn, das fruchtet, aber sie lenken den Blick nicht so dahin, daß dieser Blick innerlich wird, im innerlichen Hören und im innerlichen Schauen lebendig wird. Erst wenn wir das, was an der Außenwelt erlebt wird, zum innerlichen Bilde machen, erst dann haben wir dasjenige, was Vorbereitung sein kann. Die Seele muß sich an dem Äußerlichen entzünden, die Seele muß sich an dem Äußerlichen beleben. Denn spräche man dasjenige, was nun die ganze Natur bedeutet, man würde zunächst zu tauben Seelenohren und zu blinden Seelenaugen sprechen, und man würde auch dasjenige noch den Menschen nehmen, was sie an wenigem haben. Man gibt ihnen nur etwas, wenn man versteht, zu ihrer Seele zu sprechen, zu ihrer Seele so zu sprechen, wie der Christus-Jesus zu den Jüngern sprechen durfte, die an dem Miterleben mit ihm ihre Seelen erregt und lebendig gemacht haben. Die Seele muß erregt werden und lebendig gemacht werden an dem Äußeren, und ist sie lebendig gemacht, dann kann man erst zu der Seele von der Auslegung desjenigen sprechen, was in Naturgleichnissen vor den Menschen hingestellt ist. Und in diesem Sinne lenke man auch den Menschen zunächst auf Naturvorgänge und versuche, die Naturvorgänge in seelenwirkende Bilder zu wandeln. Man mache rege, wie man miterleben kann alles das, was sonnenhaft uns umgibt. Von dem Augenblick an, wo wir des morgens aufwachen bis wir des abends uns zur Ruhe begeben, umgibt uns Sonnenhaftes. Wir haben als unvorbereitete Menschen zunächst keine Ahnung davon, was alles in dem Sonnenlichte lebt, das uns umflutet. Wir sehen das Sonnenlicht zurückgeworfen an einzelnen Gegenständen, wir sehen es zunächst in Farben sich spiegeln, aber ob dieses Sonnenhafte durch die Farben hindurch in uns Menschen, indem es durch uns hindurchflutet, noch Besonderes erregt und verlebendigt, das ahnen wir zunächst nicht. Wir befinden uns einfach im Lichte vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen, und dann wenden wir uns in mondenheller Nacht zum Monde, schauen ihn an mit offenen Menschenherzen, wie er umgeben ist von den ihn begleitenden Sternen, und gehen über zu der ersten Empfindung, die wir da haben können, zu der Empfindung, daß, wenn ich in die Sonne sehe, gerade dann, wenn die Sonne am lebendigsten mit ihrem Licht mich umflutet, mein Auge geblendet wird. Der Sonne Licht ist an Intensität zu stark, als daß sich ohne weiteres das Auge zur Sonne hinwenden könnte. Sehe ich in den Mond, so kann ich es, der Mond gibt mir der Sonne Licht zurück, er schickt mir das Licht so, daß ich es aufnehmen kann. Die Blendung gegenüber dem Sonnenlicht ist eine Hinwegnahme der Besonnenheit. Diese Besonnenheit bleibt mir, wenn ich hinaufschaue zum Mondenlicht. Die Strahlen der Sonne haben eine zu majestätische Intensität, als daß sie mir nicht die Besonnenheit rauben müßten, wenn ich mich ihnen entgegenwende. Ich darf mich ihnen entgegenwenden, wenn sie mir vom Monde her wiedergegeben werden. Wie mache ich das zum eigenen inneren Erlebnis? Ich darf und kann mich als Mensch vereinigen mit demjenigen, was mir vom Monde an Licht zurückgegeben wird; ich darf, wenn ich es als Symbolum vor mich hinstelle, darin dasjenige haben, mit dem ich mich vereinigen darf. Ich darf mir von dem, was im Mondenlicht mir entgegenkommt, ein solches Bild machen, das ich mit mir vereinigen kann. Mit anderen Worten, ich darf mir ein Bild von der Sonne machen, welche durch das Mondenlicht sich mir darstellt, und das ist da in der Hostie, die ich verzehren darf. Aber ich habe darin etwas, was zu intensiv, zu majestätisch groß ist, als daß ich mich unmittelbar ihm aussetzen darf. Wenn ich das im Bilde mir darstelle, so muß ich es in anderer Weise darstellen. Ich muß eine Beziehung herstellen, die nur im Anschauen ähnlich ist, und die stelle ich her, indem ich dasjenige, was die Wegzehrung werden darf, [die Hostie,] umgebe mit demjenigen, was bloß angeschaut werden darf, mit der Monstranz (Zeichnung Tafel 4), und ich habe aus meinem Verhältnis zur Welt herausgeboren ein dualistisches Gleichnis, die zweifache Art, wie ich etwas zum Bilde mache mit dem Einschluß der Monstranz. In der Wegzehrung, in der Hostie habe ich dasjenige, das ich mit mir vereinigen kann. In demjenigen, was die Hostie umgibt, habe ich das, was die zum Bilde abgeschwächten Strahlen der Sonne sind. In mir muß durch die Kommunion dasjenige rege werden, was in Abschwächung erscheint, wenn ich das Mondenlicht fühle, das ich aber nicht mehr fühlen darf in seiner unmittelbaren Sonnenwirkung, sonst werde ich geblendet. Zwischen beiden mittendrin liegt die Kommunion: Ich ordne mich ein in den Weltenzusammenhang. Das, was im Kosmos Sonne und Mond miteinander zu sprechen haben, das begegnet sich im Menschen, der Mensch steht mittendrinnen und macht es lebendig durch die Kommunion.

[ 18 ] Sehen Sie, so wird weiter als zum gesprochenen Gleichnis, so wird zum Symbolum heruntergebracht dasjenige, was erlebt werden kann. Und wird es im rechten Sinne erlebt, das heißt so erlebt, daß man es mit den anderen erlebt, bei völligem Verständnis des Wortes «Und er streckte die Hand über seine Jünger aus und sprach: Siehe, das sind meine Eltern und meine Brüder», dann stellt man gewissermaßen die Menschengemeinschaft hin durch das Fühlen dieses Wortes, dann tritt man gemeinschaftsbildend auf; und gerade die Lehre, wie gemeinschaftsbildend aufgetreten werden kann, die werden wir wiederfinden, wenn wir weiter fortschreiten in der Interpretation von Matthäus 13.

[ 19 ] Meine lieben Freunde, es ist aus innerer Erkenntnis heraus, die einem das anthroposophische Überschauen der Menschheitsentwikkelung geben kann, meine volle Überzeugung, daß es gerade für die Gegenwart schlimm wäre, wenn wir heute die Zeichen, die nun einmal in der Zeit da sind, überhören würden, wenn wir uns ihnen nicht hingeben würden. Bedenken Sie, gerade indem Sie Ihren Seelenblick auf so etwas wie das Matthäus-Evangelium Kapitel 13 fallen lassen, das folgende: Die katholische Kirche bleibt beim Symbolum zunächst stehen; was in ihr gemeinschaftsbildend auftrat, war an das Symbolum gebunden, das Symbolum, das die Reiche der Himmel erleben ließ. Gar nicht eingefallen wäre es denjenigen, die in den ersten Jahrhunderten das Christentum ausgebreitet haben, davon zu sprechen, daß man Geduld haben muß, daß man warten könne und so weiter. Das bin ich schon verpflichtet zu sagen. Sie waren ganz erfüllt von der Notwendigkeit der Tat, denn sie empfanden die Wirksamkeit des Symbolums und wirkten mit dem Symbolum gemeinschaftsbildend. Sie trafen durch das Symbolum dasjenige, was der Christus andeuten wollte in den Worten, die verzeichnet sind in den sieben Gleichnissen vom Reiche Gottes. Sie wollten durch das Symbolum die Ohren hörend und die Augen sehend machen, bevor sie mit der Verkündigung begannen; sie standen darinnen in der lebendigen Welt des Symbolismus.

[ 20 ] Wir stehen heute in einer völlig veränderten Zeit darinnen. Wir lesen in dem 13. Kapitel des Matthäus-Evangeliums, daß zunächst nur den Jüngern auseinandergesetzt werden soll, was in den Gleichnissen liegt. Das können wir heute ja nicht. Das ist ja heute unmöglich, denn das Evangelium ist in aller Hände, und die Deutung der Gleichnisse kann jeder lesen. Wir leben in einer völlig veränderten Zeit. Darauf achten wir gewöhnlich gar nicht. Wir müssen neu verstehen, was im Matthäus-Evangelium Kapitel 13 liegt, wir müssen uns im Sinne unserer Zeit dazu verhalten können, wenn wir uns die Struktur von Matthäus 13 vor das Auge stellen. Wir haben zunächst: Der Christus sitzt vor dem Volke, er gibt ihnen Gleichnisse von dem Reiche der Himmel, und vom 36. Satz an heißt es dann: «Da verließ Jesus das Volk und kam heim, und seine Jünger traten zu ihm und sprachen: Deute uns das Gleichnis vom Unkraut auf dem Acker. Und er deutete es ihnen.» Machen wir uns auch diese Situation völlig klar. Zunächst spricht der Christus zu dem Volke in Gleichnissen, die in äußere Geschehnisse gekleidet sind. Er deutet die Gleichnisse seinen Jüngern. Er spricht während dieser Deutung das bedeutungsvolle Mysterienwort, das ich versucht habe, Ihnen näherzubringen. Nachdem der Christus zu Hause angekommen ist und den Jüngern noch das Gleichnis vom Unkraut gedeutet hat, spricht er zu ihnen eine Anzahl von anderen Gleichnissen, das vom Schatz im Acker, das von der köstlichen Perle, das vom ausgeworfenen Fischernetz. Er spricht also auch andere Gleichnisse zu den Jüngern, nachdem schon das Volk fortgegangen ist. Das gehört alles zur Situation; im Evangelium ist eben alles wichtig. Wir haben also — stellen wir uns das deutlich vor die Seele- den Christus am Meere sitzend vor dem Volke, ihm Gleichnisse erzählend, dann sich abwendend, vor die Jünger sich wendend, sie in die Situation hineingeleitend, ein wichtiges Mysterienwort aussprechend, dann abseits vom Volke mit ihnen allein sprechend und ihnen eines der bedeutsamsten Gleichnisse erläuternd, andere Gleichnisse zu ihnen sprechend und dann, nachdem er sie noch einmal an die göttlich-geistigen Erscheinungen hingeleitet hat, sie fragend, ob sie ihn verstanden haben. Ihre Antwort ist «Ja». Und der zunächstliegende Schluß ist — denn alles andere ist Ausleitung —: Sie sollen nun zunächst als Eingeweihte der Schrift sich so verhalten wie ein Hausvater, der aus seinem Schatz dasjenige nimmt, das er erfahren hat, der sich aber an dem, was er erfahren hat, innerlich so lebendig macht, daß er Neues hinzufügen kann und das alles dann wiederum seinen Hörern vorzutragen in der Lage ist.

[ 21 ] Ich wollte Ihnen heute den Weg zeigen, der uns hingeleiten kann zu Matthäus 13, und wir wollen dann morgen weiter sprechen von den Wahrheitsgehalten und von den Lebensgehalten, die auf diesem Wege in den Evangelien gefunden werden können. Ich habe nur als eine Einfügung angedeutet, wie auf diesem Wege die Symbolik gefunden wird an einem zentralen Symbolum, von dem nun allerdings geglaubt werden muß, meine lieben Freunde, daß es auch ein Zentralsymbolum werden müßte für diejenigen, die wiederum den Kultus einführen wollen in die Seelsorge. Denn da braucht man eben dasjenige, was anschaulich ist als Symbolum, das mehr bedeutet als das Naturprodukt, und man braucht dann das Wort, das lebendig ist, und man braucht die Handlung, die nicht bloß Naturhandlung ist. Wir haben in unserem heutigen Zivilisationszusammenhang nur das tote Wort, nicht das lebendige Wort. Wir haben nur die Handlungen, auch in den Menschenhandlungen, die Naturgesetzmäßigkeiten in sich enthalten. Wir haben weder das lebendige Wort noch die vom göttlichen Willen durchtränkte Handlung. Zu beiden müssen wir kommen im Gebet und im Evangeliumlesen auf der einen Seite und im rechten Vollbringen des Opfers auf der anderen Seite. Davon dann morgen.

Eighth Lecture

[ 1 ] My dear friends! The question which we approached from the anthroposophical side yesterday and in fact already in the previous days is now to be approached from the religious side, and again I do not want to do this in definitions and explanations, but rather I would like to suggest the path more concretely. As you may have sensed, it is indeed a path that must start from the very characteristic aspects of religious experience. Now, the reality of prayer and the reality of the examination of the word belong to religious experience, initially becoming clear to us in the examination of the word of the Gospels. We will then have to consider the more inward elements of religious life, but we will stick to these two, to prayer and to the hearing of the word of the gospel, through examples that are better than concepts.