The Study of Man

GA 293

Lecture XIII

4 September 1919, Stuttgart

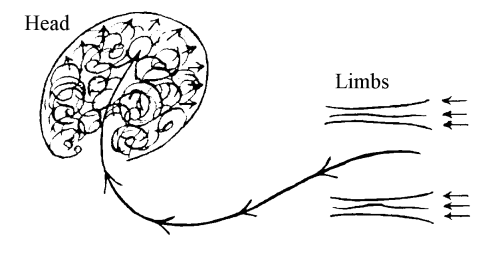

The insight we have won through these lectures will enable us to understand man in his relationship to the world around him. It will enable us also to deal with the child in his relationship to the world. It is only a question of being able to apply this insight in life in the right way. We have to think of the relation of man to the outside world as twofold, for we have found that the constitution of the limb man is in complete contrast to that of the head man. We must accustom ourselves to the difficult thought that the only way to understand the forms of the limb man is to imagine the head forms turned inside out like a glove or stocking. And in this is an expression of something of great significance in the whole life of man. If we were to draw it as a diagram we might say: the head is formed as though it were pressed outwards from within, is “bulged” outwards from within. The limbs of man we can picture as pressed inwards from without through being turned inside out at the forehead. (This turning inside out is a process of great significance in the life of man.) Consider your forehead, and imagine that your inner being is striving from within outwards towards your forehead. Now on the palm of your hand or on the sole of your foot, a kind of pressure is being exercised, like the pressure on your forehead from within, only in the reverse direction. So that when you hold your hand with the palm facing outwards, or when you place the sole of your foot on the ground, there streams from without through your sole, or through your palm, what streams towards your forehead from within. This is a fact of remarkable importance. It is so very important because it enables us to see the actual disposition of the spiritual-soul element in man.

This spirit-soul element, as you now see, is a stream. The spirit-soul passes through man as a stream, as a current.

And what is man in respect to this soul and spirit? Imagine a flowing stream of water stopped by a dam, so that it is checked and floods back on itself. So does the spirit and soul gush over in man. The human being is like a dam for the spirit and soul. They might flow through him unhindered, but he retards and keeps them back. Man causes spirit and soul to be dammed up within him. Now this process, which I have likened to a stream, is a very remarkable one. I have likened the active flow of spirit and soul through man to a stream. But actually—what is it from the point of view of the external bodily nature? It is a perpetual suction of the human being. Man confronts the external world. Spirit and soul are continuously striving to absorb him, to suck him in. This is why we continuously shed flakes and bits of ourselves. And if the spirit is not strong enough to do it we have to cut off bits of ourselves, e.g. the finger nails—because the spirit, coming from without, seeks to devour and destroy them. The spirit destroys everything, and the body checks this destructiveness of the spirit. And in man a balance must be created between the destructive spirit and soul and the continually constructive activity of the body. The chest abdomen system is inserted amidst this stream. And it is this chest abdomen system which throws itself against the destructive onset of spirit and soul, and which permeates the human being with the material substance it produces. From this you will see that the limbs of man which reach out beyond the chest abdomen system are really the most spiritual thing of all, for there is less of the substance-creating process going on in the limbs than anywhere else in man. The only thing that brings a material element into the limbs is that part of the metabolic process which is sent into the limbs by the chest abdomen system. Our limbs are spirit to a high degree, and it is the limbs which consume our body when they move.

And the task of the body is to develop in itself what is potentially in man from his birth. If the limbs move too little or move in the wrong way, they do not consume enough of the body. The abdomen chest system is then in the fortunate position—fortunate, that is, for itself—that an insufficient quantity of it is consumed by the limbs. It uses what is left over to produce surplus substantiality in man. This surplus substantiality then permeates what is native to man from his birth, that is, the bodily nature proper to him as a being born of spirit and soul. It permeates what he ought to have with something he ought not to have, with a substantiality which belongs to his earthly nature only, a substantiality having no tendency to spirit and soul in the true sense of the words: it permeates him with fat. Now when this fat is deposited in man to an abnormal extent it causes too much obstruction to the incoming consuming process of spirit and soul; with the result that the path of this spirit and soul process to the head system is made difficult. For this reason it is not right to allow children to have too much fat producing food. It causes their heads to be separated off from the soul-spiritual stream. For fat obstructs soul and spirit, and renders the head empty. It is a question of having the tact to co-operate with the child's home life and see to it that he does not get too fat. Later in life getting fat depends on all kinds of other things, also some abnormally constituted children tend to get fat because they are weak—but with normal children it is always possible to prevent excessive fat by giving a suitable diet.

We shall not, however, have the right feeling of responsibility towards these things unless we appreciate their very great significance. We must realise that if we allow the child to accumulate too much fat we are encroaching on the work of the world process. The world has a purpose to achieve in man, which it signifies by letting soul and spirit flow through him. We definitely encroach on a cosmic process if we let the child get too fat.

Now something very remarkable happens in man's head: as all spirit and soul is dammed up there it splashes back like water meeting a weir. It is like this: the spirit and soul brings matter with it, as the Mississippi brings sand, and this matter sprays back right inside the brain; thus where spirit and soul is dammed up we have streams surging one over the other. And in this beating back of the material element matter is continually perishing in the brain. And when matter, which is still permeated with life, collapses and is driven back, as I described, there then arises the nerve. Nerve comes into existence wherever matter which has been driven through life by the spirit perishes and decays within the living organism. Hence nerve is decayed matter within the living organism: life gets jammed, as it were, gets dammed up in itself, matter crumbles away and decays. Hence arise channels in all parts of the body filled with decayed matter, these are the nerves. Here spirit and soul can play back into man. Spirit and soul sprays through man along the nerves; for spirit and soul makes use of the decayed matter. It causes matter to decay, to flake off on the surface of man's body. Indeed spirit and soul will not enter man's body and permeate it until matter has died within it. The spirit and soul element in man moves within him along the nerve channels of lifeless matter.

In this way we can see how spirit and soul actually operates in man. We see it pressing upon him from outside, developing, as it does so, a devouring, consuming activity. We see it penetrating into him. We see how it is checked, how it splashes back, how it kills matter. We see how matter decays in the nerves, and how this enables the spirit and soul to make its way even to the skin, from within outwards, along the pathways of its own making. For spirit and soul cannot pass through what has organic life.

Now, how can you picture the organic, the living element? You can picture it as something that takes up spirit and soul into itself, that does not let them through. And you can picture the dead material, mineral element as something that lets the spirit and soul through. So that you can get a kind of definition for the living-organic element and a definition for the bone-nerve element, and indeed for the material-mineral element as a whole. For the living-organic element is impermeable for the spirit. The dead physical element is permeable for the spirit. “Blood is a very special fluid,” for as opaque matter is to light, so is blood to the spirit. It does not let the spirit through. It retains the spirit within it. Nerve substance is a very special substance, also. It is to spirit as transparent glass is to light. As transparent glass lets the light through, so, too, physical matter, material nerve substance lets the spirit through.

Here we have the difference between two component parts of the human being, that in him which is mineral, which is permeable to the spirit, and that in him which is more animal, more of a living organism, and which retains the spirit within him—that which causes the spirit to produce the forms which shape the organism.

From this many things follow for the treatment of the human being. For example, when a man does bodily work he moves his limbs. This means he is entirely immersed, he is swimming about in the spirit. This is not the spirit that has dammed itself up within him, this is the spirit that is outside him. If you chop wood, or if you walk—whenever you move your limbs in work of some sort—whether useful or not—you are constantly splashing about in spirit; you are concerned constantly with spirit. This is very important. And, further it is important to ask ourselves: What if we are doing spiritual work, if we are thinking or reading—how is it then? Well, this is a concern of the spirit and soul that is within us. Now it is not we who splash about in spirit with our limbs, but the spirit and soul is at work in us and continuously makes use of our bodily nature; that is, spirit and soul come to expression wholly as a bodily process within us. And here within us by means of this damming up, matter is constantly being thrown back upon itself. In spiritual work the activity of the body is excessive, in bodily work, on the other hand, the activity of the spirit is excessive. We cannot do spiritual work, work of soul and spirit, except with the continuous participation of the body. When we do bodily work the spirit and soul within us takes part only in so far as our thoughts direct our walking, or guide our work. But the spirit and soul nature takes part in it from without. We continuously work into the spirit of the world, we continuously unite ourselves with the spirit of the world when we do bodily work. Bodily work is spiritual; spiritual work is bodily, its effect is bodily upon and within man. We must understand this paradox and make it our own, namely that bodily work is spiritual and spiritual work bodily, both in man and in its effects on man. Spirit is flooding round us when do bodily work. Matter is active within us when we do spiritual work.

We must know such things, my dear friends, if we are to think with understanding about work—whether spiritual or bodily work—and about recreation and fatigue. We can only do this if we have a thorough grasp of what I have just described. For, suppose a man works too much with his limbs, that he does too much bodily work, what is the result? It brings him too much into relation with the spirit. For spirit continually floods round him when he does bodily work; consequently the spirit gains too much power over man, the spirit that comes from outside. We make ourselves too spiritual when we do too much bodily work. From without we let ourselves be made too spiritual. And it follows that we need to give ourselves up to the spirit for too long, in other words, we have to sleep too long. And too much sleep in turn promotes too much bodily activity, the bodily activity of the chest abdomen, not of the head system. This activity over-stimulates life, we become feverish, too hot. Our blood pulses in us too strongly its activity in the body cannot be assimilated, if we sleep too much. Nevertheless through excessive bodily work we produce in ourselves the desire to sleep too much.

But what about lazy people who love to sleep, and who sleep so much? Why are they like this? It is due to the fact that man can never really stop working. When a lazy person sleeps it is not because he works too little, for a lazy person has to move his legs all day long, and he flourishes his arms about, too, in some fashion or other. Even a lazy person does something. From an external point of view he really does no less than an industrious person—but he does it without sense or purpose. The industrious man turns his attention to the outside world, He introduces meaning into his activities. That is the difference. Senseless activities such as a lazy person carries on are more conducive to sleep than are activities with a purpose in them. In intelligent occupation we do not merely splash about in the spirit: if there is meaning in the movements we carry out in our work we gradually draw the spirit into us. When we stretch out our hand with a purpose we unite ourselves with the spirit; and the spirit, in its turn, does not need to work so much unconsciously in sleep, because we are working with it consciously. Thus it is not a question of whether man is active or not, for a lazy man too is active, but the question is how far man's actions have a purpose in them. To be active with a purpose—these words must sink into our minds if we would be teachers. Now when is a man active without purpose? He is active without purpose, senselessly active, when he acts only in accordance with the demands of his body. He acts with purpose when he acts in accordance with the demands of his environment and not merely in accordance with those of his own body. We must pay heed to this where the child is concerned. It is possible, on the one hand, to direct the child's outer bodily movements more and more to what is purely physical, that is, to physiological gymnastics, where we simply enquire of the body what movements shall be carried out. But we can also guide the child's outer movements so that they become purposeful movements, movements penetrated with meaning, so that the child does not merely splash about in the spirit in his movements, but follows the spirit in his aims. So we develop the bodily movements into Eurythmy. The more we make the child do purely physical gymnastics the more he will be at the mercy of excessive desire for sleep; and of an excessive tendency to fat. We must not entirely neglect the bodily side, for man must live in rhythm, but having swung over to this side we must swing back again to a kind of movement which is permeated with purpose—as in Eurythmy, where every movement expresses a sound and has a meaning—the more we can alternate gymnastics with Eurythmy the more we shall bring harmony into the need for sleeping and waking; the more, too, shall we maintain normal life in the child's will, in his relations to the outer world. That gymnastics, moreover, has become void of all sense or meaning, that we have made it into an activity that follows the body entirely, is a characteristic phenomenon of the age of materialism. And the fact that we seek to “raise” this activity to the level of sport, where the movements to be performed are derived solely from the body, and not only lack all sense and meaning, but are contrary to sense and meaning—this fact is typical of the endeavour to drag man down even beyond the level of materialistic thinking to that of brute feeling. The excessive pursuit of sport is Darwinism in practice. Theoretical Darwinism is to assert that man comes from the animals. Sport is practical Darwinism, it proclaims an ethic which leads man back again to the animal.

One must speak of these things to-day in this radical manner because the present-day teacher must understand them; for, not only must he be the teacher of those children entrusted to his care, he must also work socially, he must work back upon mankind as a whole to prevent the increasing growth of things which would tend indeed to have an animalising effect upon humanity. This is not false asceticism. It comes from the objectivity of real insight, and is as true as any other scientific knowledge.

Now what is the position with regard to spiritual work? Spiritual work, thinking, reading and so on, is always accompanied by bodily activity and by the continual decay and dying of organic matter. When we are too active in spirit and soul we have decayed organic matter within us. If we spend our entire day in learned work we have too much decayed organic matter in us by the evening, This works on in us, and disturbs restful sleep. Excessive spiritual work disturbs sleep just as excessive bodily work makes one sleep-sodden. But when we exert ourselves too much over soul-spiritual work, when, for instance, we read something difficult, and really have to think as we read (not exactly a favourite occupation nowadays), if we do too much difficult reading we fall asleep over it. Or if we listen, not to the trite platitudes of popular speakers or others who only say what we already know, but to people whose words we have to follow with our thoughts because they are telling us what we do not yet know—we get tired and sleep-sodden. It is well known that people who go to a lecture or concert because it is “the thing to do”, and do not give real thought or feeling to what is put before them, fall asleep at the first word, or the first note. Often they will sleep all through the lecture or concert which they have attended only from a sense of duty or of social obligation.

Now here again are two kinds of activity. Just as there is a difference between outward activity which has meaning and purpose and that which has no meaning, so there is a difference between the inner activity of thought and perception which goes on mechanically and that which is always accompanied by feelings. If we so carry out our work that continuous interest is combined with it, this interest and attention enlivens the activity of our breast system and prevents the nerves from decaying to an excessive degree. The more you merely skim along in your reading, the less you exert yourselves to take in what you read with really deep interest—the more you will be furthering the decay of substance within you. But the more you follow what you read with interest and warmth of feeling the more you will be furthering the blood activity, that is, that activity which keeps matter alive. And the more, too, you will be preventing mental activity from disturbing your sleep. When you have to cram for an examination you are assimilating a great deal in opposition to your interest. For if we only assimilated what aroused our interest we should not get through our examinations under modern conditions. It follows that cramming for an examination disturbs sleep and brings disorder into our normal life. This must be specially borne in mind where children are concerned. Therefore for children it is best of all, and most in accordance with an educational ideal, if we omit all cramming for examinations. That is, we should omit examinations altogether and let the school year finish as it began. As teachers we must feel it our duty to ask ourselves: why should the child undergo a test at all? I have always had him before me and I know quite well what he knows and does not know. Of course under present-day conditions this must remain an ideal for the time being. And I must beg you not to direct your rebel natures too forcibly against the outside world. Your criticism of our present-day civilisation you must turn inwards like a goad, so that you may work slowly—for we can only work slowly in these things—towards making people learn to think differently; then external social conditions will change their present form.

But you must always remember the inner connection of things. You must know that Eurythmy, external activity permeated with purpose, is a spiritualising of bodily activity, and the arousing of interest in one's teaching (provided it is genuine) is literally a bringing of life and blood into the work of the intellect.

We must bring spirit into external work, and we must bring blood into our inward, intellectual work. Think over these two sentences, and you will see that the first is of significance both in education and in social life, and that the second is of significance both in education and in hygiene.